To estimate vertical HIV transmission rate in a capital city of the Midwest region of Brazil and describe the factors related to transmission.

MethodsA descriptive epidemiological study based on the analysis of secondary data from the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN). The analysis considered all HIV-infected pregnant women with delivery in Campo Grande-MS in the years 2007–2013 and their HIV-exposed infants.

ResultsA total of 218 births of 176 HIV-infected pregnant women were identified during the study period, of which 187 infants were exposed and uninfected, 19 seroconverted, and 12 were still inconclusive in July 2015. Therefore, the overall vertical HIV transmission rate in the period was 8.7%. Most (71.6%) of HIV-infected pregnant women were less than 30 years at delivery, housewives (63.6%) and studied up to primary level (61.9%). Prenatal information was described in 75.3% of the notification forms and approximately 80% of pregnant women received antiretroviral prophylaxis. Among infants, 86.2% received prophylaxis, but little more than half received it during the whole period recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. Among the exposed children, 11.3% were breastfed.

ConclusionThe vertical HIV transmission rate has increased over the years and the recommended interventions have not been fully adopted. HIV-infected pregnant women need adequate prophylactic measures in prenatal, intrapartum and postpartum, requiring greater integration among health professionals.

The dynamics of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection have changed over time. Initially its spread was identified among men who had sex with men. After some time, there was a pattern change with increased heterosexual transmission of HIV and thus increased incidence of infection in women. Still, the identification of HIV in small cities and low-income population shows the infection is no longer restricted to risk groups, but to those under risk behavior.1

The increasing number of HIV-infected women, especially of childbearing age, increases the risk of children to be infected by vertical transmission.2,3 Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) incidence in children under five years is the indicator used to monitor vertical HIV transmission. In 1998, the Brazilian incidence rate of AIDS in children under five years was 5.9/100,0004 and this rate reduced to 2.8/100,000 in 2013.5 Much of this reduction was due to the availability of zidovudine, as it reduces by two-thirds the possibility of HIV transmission during pregnancy and delivery.6 Other prophylactic measures, such as antiretroviral therapy (ART) to the exposed infant, cesarean delivery, replacement of breastfeeding by artificial feeding are part of the current protocol recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.7

For proper epidemiological surveillance, the reporting of cases of AIDS began in 1986.8 In 2000, the Brazilian Ministry of Health established compulsory notification of HIV infection in pregnant women, whose notification form also contemplated information about the exposed infants.9 In 2007, the joint notification of pregnant women and newborns was disconnected due to operational difficulties related to the place of care. So, it was established a specific notification tool for exposed children and another instrument for HIV infection in pregnant women.10

Despite all the existing interventions, vertical HIV transmission is still a reality. Thus, the aim of this study was to estimate vertical HIV transmission rate in a capital city of the Midwest region of Brazil and describe the factors related to transmission.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationThis descriptive epidemiological study was based on the analysis of secondary data from the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN). The analysis considered all HIV-infected pregnant women with delivery in Campo Grande-MS in the period of 2007 to 2013 and their HIV-exposed infants.

All mothers included in the study had documented HIV infection before or during pregnancy, at the time of admission for delivery or while breastfeeding. Infections were documented by the result of positive serology for HIV-1 by ELISA and confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence or Western Blot test.

To be considered infected, the exposed infant should have a positive screening test (ELISA) confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence or Western Blot. Closing of cases was possible at 12 months for those infants who had two results of an undetectable viral load and negative result for anti-HIV, or at 18 months for those who had one result of an undetectable viral load and negative anti-HIV.

The vertical HIV transmission rate was calculated using number of exposed children who seroconverted in the numerator and the total number of HIV-positive pregnant women in the period in the denominator, multiplied by 100.

Data collection and analysisA database was organized to collect information regarding HIV-infected pregnant women (education, race, occupation, age at delivery, prenatal care, antiretroviral prophylaxis during pregnancy and delivery, type of delivery) and their exposed infants (antiretroviral prophylaxis, weeks of prophylaxis, and breastfeeding). These epidemiological data were obtained from notification forms of HIV-positive pregnant women and HIV exposed children.

For purposes of this study, prenatal care was considered as any number of medical or nursing appointments during pregnancy. The record of any breastfeeding at any time and for any duration was defined as “breastfeeding present”. In addition, infant anti-HIV positivity or death within 60 days was used as criteria to define possible infection in uterus, while identification of infection after 60 days was considered as intrapartum infection. The identification of HIV infection in the baby using PCR was not performed.

The univariate assessment of the association between HIV infection and age at delivery, prenatal care, antiretroviral use during pregnancy and delivery, type of delivery, weeks of antiretroviral prophylaxis to the exposed infant, and breastfeeding were performed using the chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis, using the “Enter” method, was performed to assess the association between the presence or absence of infection and the other variables assessed in this study. The results of the statistical analysis are presented as p-values, odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 22.0, considering a 5% significance level.

Ethical aspectsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Human Beings of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul under the CAAE number 05705412.0.0000.0021.

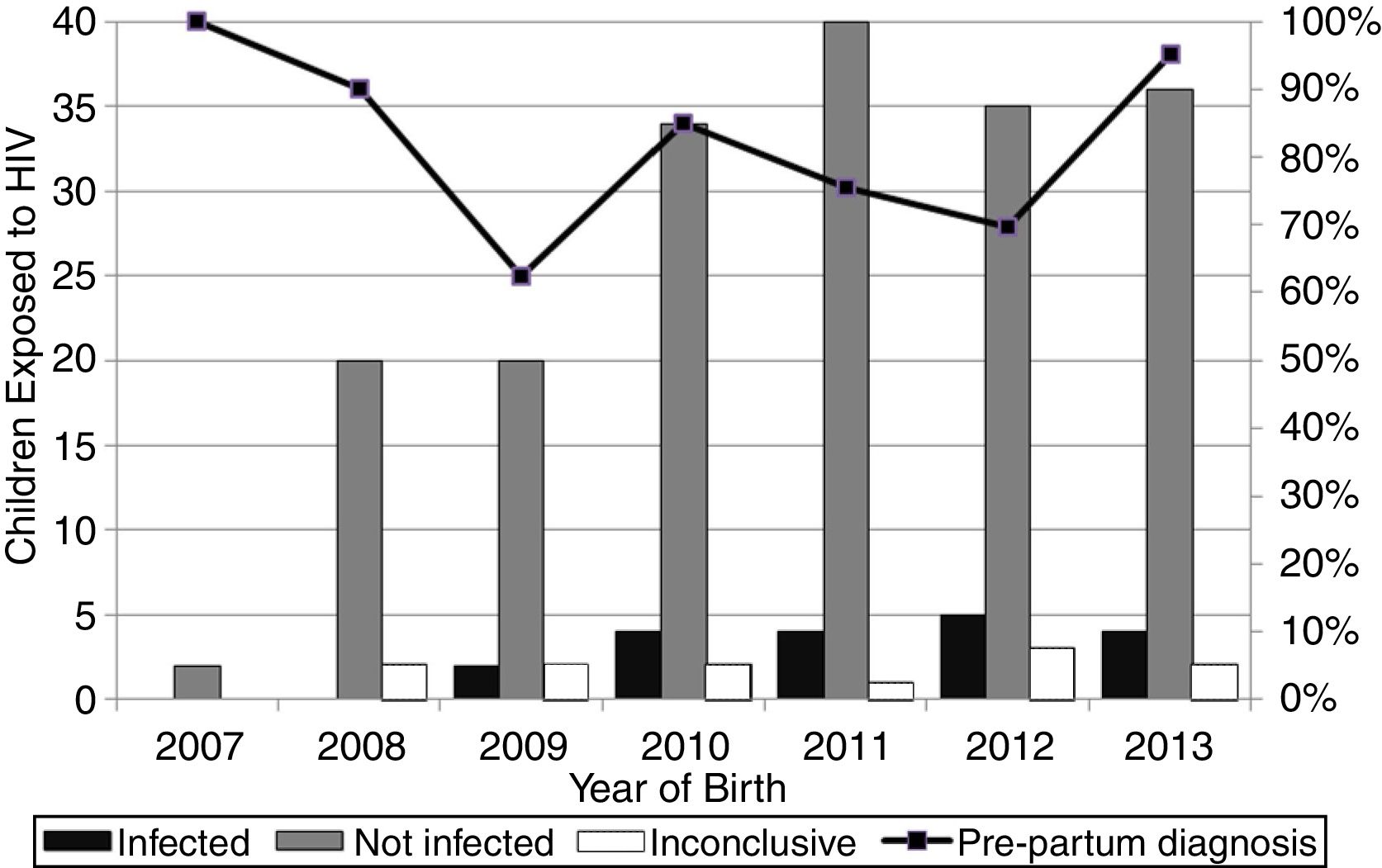

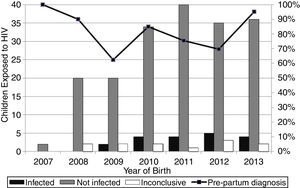

ResultsOne hundred and seventy-six HIV-infected pregnant women who delivered in Campo Grande-MS in the period of 2007 to 2013 were identified, resulting in 218 births. The number of births is higher than the number of pregnancies because some women had more than one pregnancy in the period. Of total births, 187 infants were exposed to HIV and uninfected, 19 seroconverted and 12 were still inconclusive by July 2015. Thus, the overall vertical HIV transmission rate in the period was 8.7%, while the transmission rate in 2007 (0/2) and 2008 (0/20) was 0%, 9.1% (2/22) in 2009, 10.5% (4/38) in 2010, 9.1% (4/44) in 2011, 12.5% (5/40) in 2012 and 10.0% (4/40) in 2013.

The highest vertical HIV transmission rate and the largest number of cases occurred both in Campo Grande in 2012 (Fig. 1). The women (34/176, 19.3%) with multiple pregnancies had both two (26/34, 76.5%) and three (8/34, 23.5%) deliveries.

Most (156/218, 71.6%) of HIV-infected pregnant women were less than 30 years old at delivery, housewives (112/176, 63.6%), pardo (83/176, 47.2%) and white (58/176, 33.0%), and studied up to primary level (109/176, 61.9%). Two (1.1%) of them were registered as illiterate and only five (2.9%) had higher education. The age of mothers at delivery ranged from 14 to 43 years (Table 1).

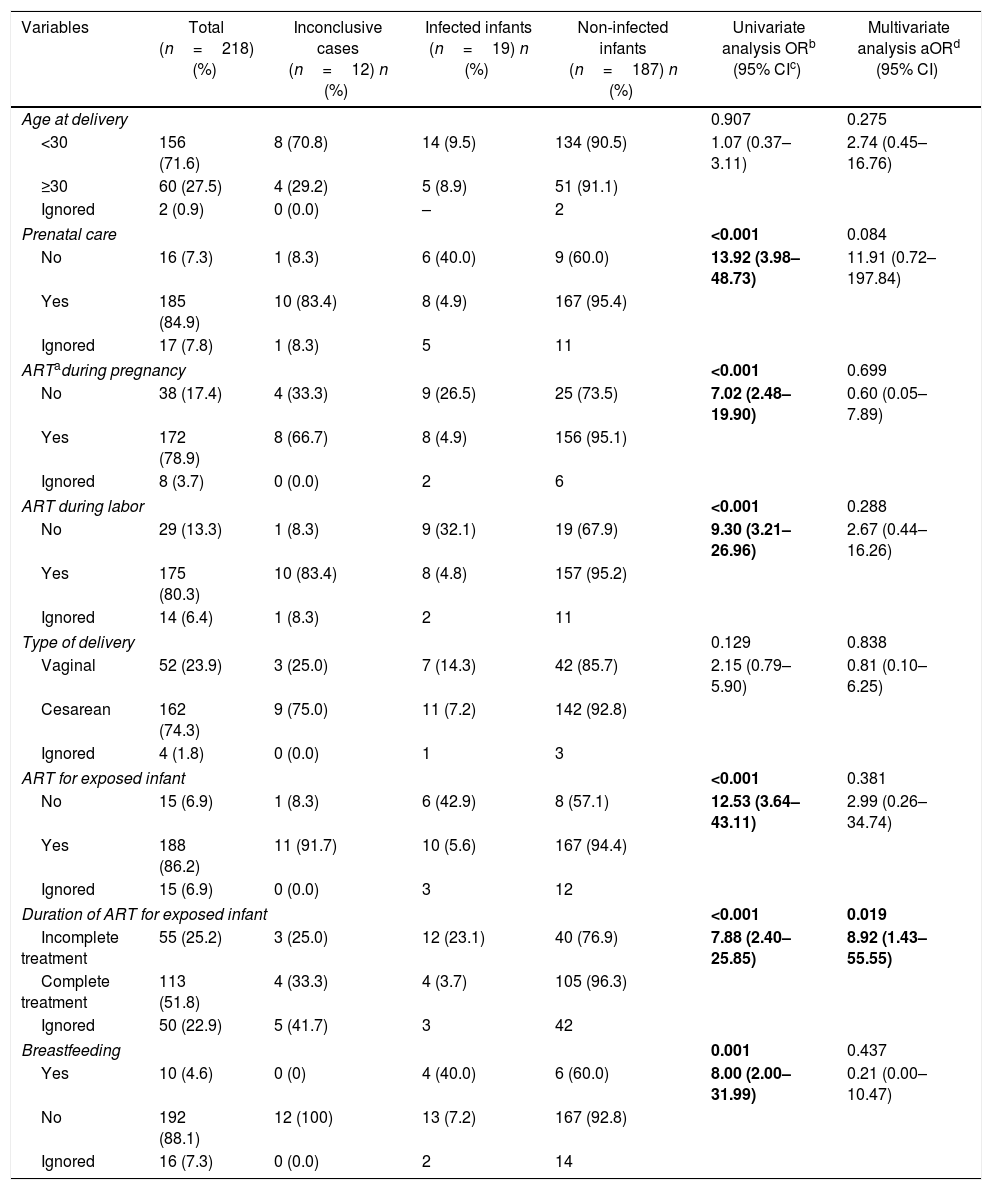

Prenatal and postnatal variables of HIV-infected pregnant women who gave birth in Campo Grande-MS from 2007 to 2013.

| Variables | Total (n=218) (%) | Inconclusive cases (n=12) n (%) | Infected infants (n=19) n (%) | Non-infected infants (n=187) n (%) | Univariate analysis ORb (95% CIc) | Multivariate analysis aORd (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at delivery | 0.907 | 0.275 | ||||

| <30 | 156 (71.6) | 8 (70.8) | 14 (9.5) | 134 (90.5) | 1.07 (0.37–3.11) | 2.74 (0.45–16.76) |

| ≥30 | 60 (27.5) | 4 (29.2) | 5 (8.9) | 51 (91.1) | ||

| Ignored | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | – | 2 | ||

| Prenatal care | <0.001 | 0.084 | ||||

| No | 16 (7.3) | 1 (8.3) | 6 (40.0) | 9 (60.0) | 13.92 (3.98–48.73) | 11.91 (0.72–197.84) |

| Yes | 185 (84.9) | 10 (83.4) | 8 (4.9) | 167 (95.4) | ||

| Ignored | 17 (7.8) | 1 (8.3) | 5 | 11 | ||

| ARTaduring pregnancy | <0.001 | 0.699 | ||||

| No | 38 (17.4) | 4 (33.3) | 9 (26.5) | 25 (73.5) | 7.02 (2.48–19.90) | 0.60 (0.05–7.89) |

| Yes | 172 (78.9) | 8 (66.7) | 8 (4.9) | 156 (95.1) | ||

| Ignored | 8 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 | 6 | ||

| ART during labor | <0.001 | 0.288 | ||||

| No | 29 (13.3) | 1 (8.3) | 9 (32.1) | 19 (67.9) | 9.30 (3.21–26.96) | 2.67 (0.44–16.26) |

| Yes | 175 (80.3) | 10 (83.4) | 8 (4.8) | 157 (95.2) | ||

| Ignored | 14 (6.4) | 1 (8.3) | 2 | 11 | ||

| Type of delivery | 0.129 | 0.838 | ||||

| Vaginal | 52 (23.9) | 3 (25.0) | 7 (14.3) | 42 (85.7) | 2.15 (0.79–5.90) | 0.81 (0.10–6.25) |

| Cesarean | 162 (74.3) | 9 (75.0) | 11 (7.2) | 142 (92.8) | ||

| Ignored | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 3 | ||

| ART for exposed infant | <0.001 | 0.381 | ||||

| No | 15 (6.9) | 1 (8.3) | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | 12.53 (3.64–43.11) | 2.99 (0.26–34.74) |

| Yes | 188 (86.2) | 11 (91.7) | 10 (5.6) | 167 (94.4) | ||

| Ignored | 15 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 | 12 | ||

| Duration of ART for exposed infant | <0.001 | 0.019 | ||||

| Incomplete treatment | 55 (25.2) | 3 (25.0) | 12 (23.1) | 40 (76.9) | 7.88 (2.40–25.85) | 8.92 (1.43–55.55) |

| Complete treatment | 113 (51.8) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (3.7) | 105 (96.3) | ||

| Ignored | 50 (22.9) | 5 (41.7) | 3 | 42 | ||

| Breastfeeding | 0.001 | 0.437 | ||||

| Yes | 10 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | 8.00 (2.00–31.99) | 0.21 (0.00–10.47) |

| No | 192 (88.1) | 12 (100) | 13 (7.2) | 167 (92.8) | ||

| Ignored | 16 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 | 14 | ||

Prenatal follow-up was performed in 185 (84.9%) deliveries. Most pregnant women (172/218, 78.9%) used antiretroviral therapy (ART), as well as most of their newborns (175/218, 80.3%). Among the 38 (17.4%) women who had not used ART during pregnancy, 12 (31.6%) had previous diagnosis of HIV infection and did not undergo any prophylaxis, 10 (26.3%) were diagnosed during prenatal consultation, 10 (26.3%) became aware of their HIV positivity shortly before delivery, three (7.9%) delivered undiagnosed for HIV infection, and in three pregnant women (7.9%) the reason for non-prophylaxis during pregnancy was unknown.

According to the notification forms, 12 women who received ART during pregnancy (12/172, 6.9%) did not receive ART at delivery. Among the mothers who reported having breastfed, two reported mixed feeding (breast and bottle).

No prenatal care (OR 13.92; 95% CI, 3.98–48.73) and no antiretroviral prophylaxis (pregnancy, labor and exposed infant) were significantly associated with a higher odds ratio for HIV transmission. In the same way, exposed infants who did not receive ART, received incomplete antiretroviral prophylaxis or were breastfed were more likely to be infected. However, in multivariate logistic regression, only the exposed infants who received incomplete antiretroviral prophylaxis were more likely to be HIV infected through vertical transmission.

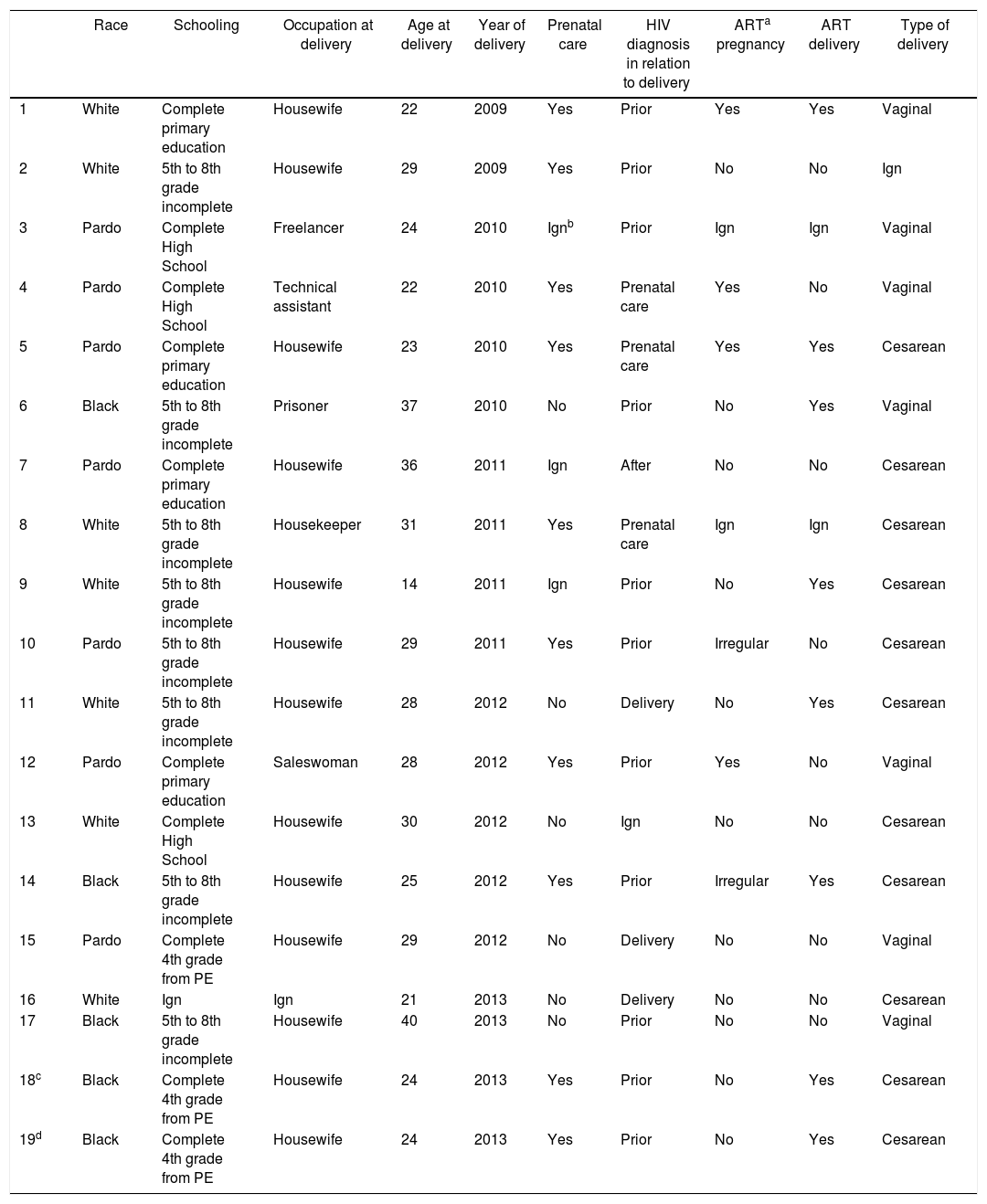

From 2007 to 2013, 19 cases of vertical HIV transmission were identified in Campo Grande. Table 2 presents the epidemiological and gestational characteristics of HIV-infected mothers whose pregnancy resulted in transmission of the virus. Patient 6 was addicted to cocaine paste and patient 13 was addicted to injecting drugs. Despite HIV diagnosis prior to delivery, pregnant women 6 and 17 had no prenatal care.

Characteristics of epidemiological and gestational HIV-infected mothers whose pregnancy resulted in transmission of the virus, Campo Grande-MS, from 2007 to 2013.

| Race | Schooling | Occupation at delivery | Age at delivery | Year of delivery | Prenatal care | HIV diagnosis in relation to delivery | ARTa pregnancy | ART delivery | Type of delivery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | White | Complete primary education | Housewife | 22 | 2009 | Yes | Prior | Yes | Yes | Vaginal |

| 2 | White | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housewife | 29 | 2009 | Yes | Prior | No | No | Ign |

| 3 | Pardo | Complete High School | Freelancer | 24 | 2010 | Ignb | Prior | Ign | Ign | Vaginal |

| 4 | Pardo | Complete High School | Technical assistant | 22 | 2010 | Yes | Prenatal care | Yes | No | Vaginal |

| 5 | Pardo | Complete primary education | Housewife | 23 | 2010 | Yes | Prenatal care | Yes | Yes | Cesarean |

| 6 | Black | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Prisoner | 37 | 2010 | No | Prior | No | Yes | Vaginal |

| 7 | Pardo | Complete primary education | Housewife | 36 | 2011 | Ign | After | No | No | Cesarean |

| 8 | White | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housekeeper | 31 | 2011 | Yes | Prenatal care | Ign | Ign | Cesarean |

| 9 | White | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housewife | 14 | 2011 | Ign | Prior | No | Yes | Cesarean |

| 10 | Pardo | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housewife | 29 | 2011 | Yes | Prior | Irregular | No | Cesarean |

| 11 | White | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housewife | 28 | 2012 | No | Delivery | No | Yes | Cesarean |

| 12 | Pardo | Complete primary education | Saleswoman | 28 | 2012 | Yes | Prior | Yes | No | Vaginal |

| 13 | White | Complete High School | Housewife | 30 | 2012 | No | Ign | No | No | Cesarean |

| 14 | Black | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housewife | 25 | 2012 | Yes | Prior | Irregular | Yes | Cesarean |

| 15 | Pardo | Complete 4th grade from PE | Housewife | 29 | 2012 | No | Delivery | No | No | Vaginal |

| 16 | White | Ign | Ign | 21 | 2013 | No | Delivery | No | No | Cesarean |

| 17 | Black | 5th to 8th grade incomplete | Housewife | 40 | 2013 | No | Prior | No | No | Vaginal |

| 18c | Black | Complete 4th grade from PE | Housewife | 24 | 2013 | Yes | Prior | No | Yes | Cesarean |

| 19d | Black | Complete 4th grade from PE | Housewife | 24 | 2013 | Yes | Prior | No | Yes | Cesarean |

It seems that technical and operational problems involving the health team occurred in the management of pregnant woman 7, whose HIV infection has not been identified before delivery and in the management of pregnant woman 12, who did not receive antiretroviral prophylaxis during labor, despite being aware of her positive serological situation. Pregnant woman 15 did not receive antiretroviral prophylaxis during labor.

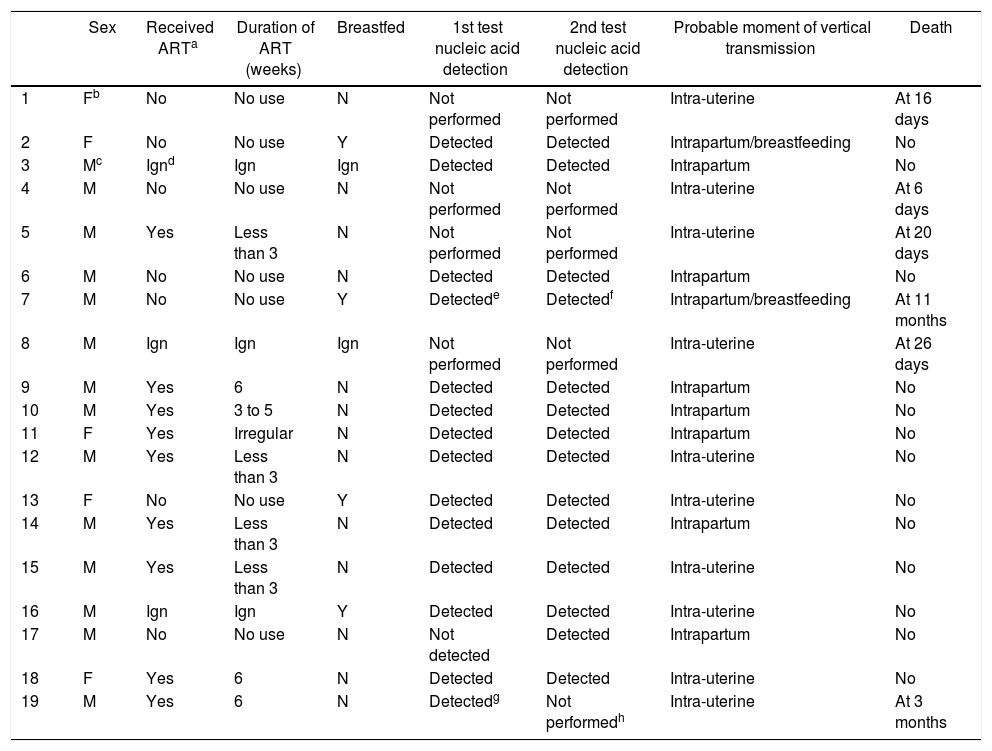

Table 3 presents the characteristics of HIV-exposed infants infected by vertical transmission between 2007 and 2013 in Campo Grande-MS. Although infection in infants 3, 6, 9 and 10 were classified as possibly intrapartum, it is possible that infection had occurred in utero. Likewise, child 7 had possibly intrapartum infection because of the nucleic acid detection date, but as no prophylactic measure for the pregnant women and for the child was used, the infection probably occurred in utero. Furthermore, child 9 was exposed to syphilis.

Characteristics of HIV-infected children by vertical transmission between 2007 and 2013 in Campo Grande-MS.

| Sex | Received ARTa | Duration of ART (weeks) | Breastfed | 1st test nucleic acid detection | 2nd test nucleic acid detection | Probable moment of vertical transmission | Death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fb | No | No use | N | Not performed | Not performed | Intra-uterine | At 16 days |

| 2 | F | No | No use | Y | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum/breastfeeding | No |

| 3 | Mc | Ignd | Ign | Ign | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 4 | M | No | No use | N | Not performed | Not performed | Intra-uterine | At 6 days |

| 5 | M | Yes | Less than 3 | N | Not performed | Not performed | Intra-uterine | At 20 days |

| 6 | M | No | No use | N | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 7 | M | No | No use | Y | Detectede | Detectedf | Intrapartum/breastfeeding | At 11 months |

| 8 | M | Ign | Ign | Ign | Not performed | Not performed | Intra-uterine | At 26 days |

| 9 | M | Yes | 6 | N | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 10 | M | Yes | 3 to 5 | N | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 11 | F | Yes | Irregular | N | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 12 | M | Yes | Less than 3 | N | Detected | Detected | Intra-uterine | No |

| 13 | F | No | No use | Y | Detected | Detected | Intra-uterine | No |

| 14 | M | Yes | Less than 3 | N | Detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 15 | M | Yes | Less than 3 | N | Detected | Detected | Intra-uterine | No |

| 16 | M | Ign | Ign | Y | Detected | Detected | Intra-uterine | No |

| 17 | M | No | No use | N | Not detected | Detected | Intrapartum | No |

| 18 | F | Yes | 6 | N | Detected | Detected | Intra-uterine | No |

| 19 | M | Yes | 6 | N | Detectedg | Not performedh | Intra-uterine | At 3 months |

The vertical HIV transmission rate in Campo Grande-MS during the period of 2007–2013 was 8.7%. It represents almost three times the Brazilian rate for the period, which ranged between 2.7% and 3.7%4 and was almost four times higher than the rate estimated at Campo Grande between 1996 and 2001.2 Also, it is far from the Ministry of Health recommended rate of 2% and it is also higher than the rate of 6.3% identified in Itajai, the Brazilian city with the highest HIV incidence.11

The reduction of vertical HIV transmission in Brazil was identified in multicenter studies since 1997,12–15 but Campo Grande results are similar to the scenario of the North and Northeast region of the country, where local studies have found transmission rates of 6.6%16 and 9.2%.17 The Southeast rates which were close to 3.0%18,19 rose again and a recent study described a rate of 5.1%.20 The other regions of Brazil have been successful in reducing this rate, with a decrease of 51.4%, 49.2%, and 40.0%, respectively, when comparing 2006 with 2016.5 HIV vertical transmission rate is less than or equal to 2.0% in the South.21,22

The low educational level18,23,24 and age at delivery less than 30 years4,8,20,25 are characteristics of HIV-infected pregnant women in Campo Grande and other regions of the country. Unawareness about prenatal care, appropriate type of delivery and lactation, adequate prophylaxis during pregnancy, delivery and to the newborn point to a health surveillance system not integrated with primary care.26

In general, the period between 2007 and 2013 was characterized by low prophylactic coverage and lack of retention of HIV-infected women in health services, with pregnant women who were aware of being HIV-infected and never used prophylaxis, pregnant women who used ART during pregnancy but not at delivery, exposed children who did not receive ART or received for a period shorter than recommended by the Ministry of Health. These failures are holding behind the goal of achieving 90.0% coverage at each step of prevention of mother-to-child transmission cascade toward reducing vertical HIV transmission.27

Despite the awareness of HIV seropositivity some barriers limit and lead to non-use or interruption of prophylaxis. Such barriers involve the HIV-infected pregnant women as they are unwilling and/or unable to comply with medical recommendations, drug-drug interactions, dosages, history of psychiatric treatment and/or drug use.28 The relationship of the health professional with the HIV-infected patient should seek the development of a good liaison, accompanied by a welcoming posture to meet specific demands and thus encourage patient's responsibility and participation in planning and deciding about their own treatment.29,30 On the other hand, no self-care and lack of interest of the HIV-infected mother about their own health condition can be extended to her newborn.31

The Brazilian guidelines for the use of ART in pregnancy indicate vaginal delivery only for mothers with viral load lower than 1000 copies after 34 weeks.7,32 However, in practice it seems difficult to ensure the safe performance of vaginal deliveries. Due to this reason, it was expected that at least the same number of pregnant women who used ART during pregnancy would have cesarean delivery.

Among the exposed children, 13.8% have not received antiretroviral prophylaxis or this information was unknown. Also, among those who received prophylactic medication, just over half received the complete regimen recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. It is necessary to consider that the infant is dependent on others for any care, including medication. Usually the mother is the main person in charge of administering the ART, but they report that the non-acceptance of their health condition, feeling of guilt and/or fear of prejudice, prevents them from correctly administer ART medication to their exposed infant.33

Few addicted to illegal drugs were identified in this study, but it is known that legal and sociocultural barriers prevent or discourage access to and use of health services. The removal of punitive measures in such cases and the creation of environments that reduce stigma and discrimination and protect human rights could contribute to HIV-infected pregnant women and their exposed infants to receive prophylaxis.34

Exposure to syphilis, identified in the child who seroconverted, increases the risk of HIV infection, once sexually transmitted infections break the mucosal barrier protection and recruit sensitive immune cells to the local infection, facilitating HIV transmission.23,35

Once the child has been vertically infected, early identification is essential for the initiation of ART, prophylaxis of opportunistic infections, and management of infectious complications and nutritional disorders. Therefore, due to the monitoring of children exposed to HIV or the intention in early detection of infection, it is important to perform the first viral load collection between four to six weeks of life. Symptomatic infants can have viral load measured at any time.36 Despite the recommendations of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, most viral load counts were performed or were documented from the fourth month on.

Many medical and non-medical technologies are available, including four HIV testing during pregnancy, but these are not properly used causing partial or none prophylaxis for vertical transmission.7 In addition, better health surveillance services articulated with primary care could overcome these barriers. By 2013, the STD/AIDS Program of Campo Grande and the Coordination of Primary Care were under the responsibility of the same Municipal Board. Even though, it was not possible to observe a reduction of vertical HIV transmission.

This study had limitations as the quality of information contained in the notification forms of HIV-infected pregnant women and the HIV-exposed infant, reflected in the number of ignored items. Overloading of nurse activities at the facility where the exposed infants were followed was a difficulty to the closure of the cases, along with the abandonment of monitoring. The involvement of the pharmacist from the Specialized Care Service (SAE) in the return of mother and exposed children could contribute to solve this problem. Further, the nucleic acid detection performed at different times made it harder to identify the time of infection, disfavoring the analysis of this result.

On the other hand, the lack of understanding of HIV-infected pregnant women regarding the consequences of HIV infection, the lack of commitment of the health team to the health of the population and to their profession itself, and the deficiency in the monitoring of drug users and adolescents by Mental Health Service were limitations in preventing vertical HIV transmission in that period.

The vertical HIV transmission rate in Campo Grande-MS is increasing over the years. The annual rates of the years 2007 to 2013 represent almost three times the Brazilian rate for the period and was almost four times higher than the rate estimated between 1996 and 2001. It was also observed the inadequate prenatal follow-up and lack of antiretroviral therapy which suggest that recommendations of the Brazilian STD/AIDS Program to reduce vertical HIV transmission are not being implemented properly.

The evaluation of health services integration, the quality of biomedical interventions as well as the impact of interventions on the social environment should be investigated to try to reduce vertical transmission rate and even eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.