In November of 2015, the Ministry of Health of Brazil published an announcement confirming the relationship between Zika virus and the microcephaly outbreak in the Northeast, suggesting that infected pregnant women might have transmitted the virus to their fetuses. The objectives of this study were to conduct a literature review about Zika virus infection and microcephaly, evaluate national and international epidemiological data, as well as the current recommendations for the health teams. Zika virus is an arbovirus, whose main vector is the Aedes sp. The main symptoms of the infection are maculopapular rash, fever, non-purulent conjunctivitis, and arthralgia. Transmission of this pathogen occurs mainly by mosquito bite, but there are also reports via the placenta. Microcephaly is defined as a measure of occipto-frontal circumference being more than two standard deviations below the mean for age and gender. The presence of microcephaly demands evaluation of the patient, in order to diagnose the etiology. Health authorities issued protocols, reports and notes concerning the management of microcephaly caused by Zika virus, but there is still controversy about managing the cases. The Ministry of Health advises notifying any suspected or confirmed cases of children with microcephaly related to the pathogen, which is confirmed by a positive specific laboratory test for the virus. The first choice for imaging exam in children with this malformation is transfontanellar ultrasound. The most effective way to control this outbreak of microcephaly probably caused by this virus is to combat the vector. Since there is still uncertainty about the period of vulnerability of transmission via placenta, the use of repellents is crucial throughout pregnancy. More investigations studying the consequences of this viral infection on the body of newborns and in their development are required.

In November of 2015, the Ministry of Health (MOH) of Brazil issued a bulletin confirming the relationship between Zika virus (ZIKV) infection and the microcephaly outbreak in the northeastern region.1

One of the first records of ZIKV disease in the country is from March of 2015, in the state of Bahia, Northeast Brazil, in which patients with “dengue-like syndrome” showed positivity in blood analysis by molecular biology (real time PCR-RT-PCR).2 Autochthonous transmission by ZIKV was confirmed in Brazil in April 20153 and in May of the same year, the Brazilian MOH confirmed the circulation of the virus.4

From an obstetric perspective, in October of 2015 there was an unusual increase in the number of newborns with microcephaly in the state of Pernambuco (Northeast). Considering that some of the mothers of these babies had a rash during pregnancy5 the possibility of ZIKV transmission from mother to child, causing neurological defects in the child, was suggested. After conducting tests in a baby born with microcephaly and other malformations in one of the Northeastern states, the presence of the virus in blood and tissues of the patient was detected, proving that assumption.4

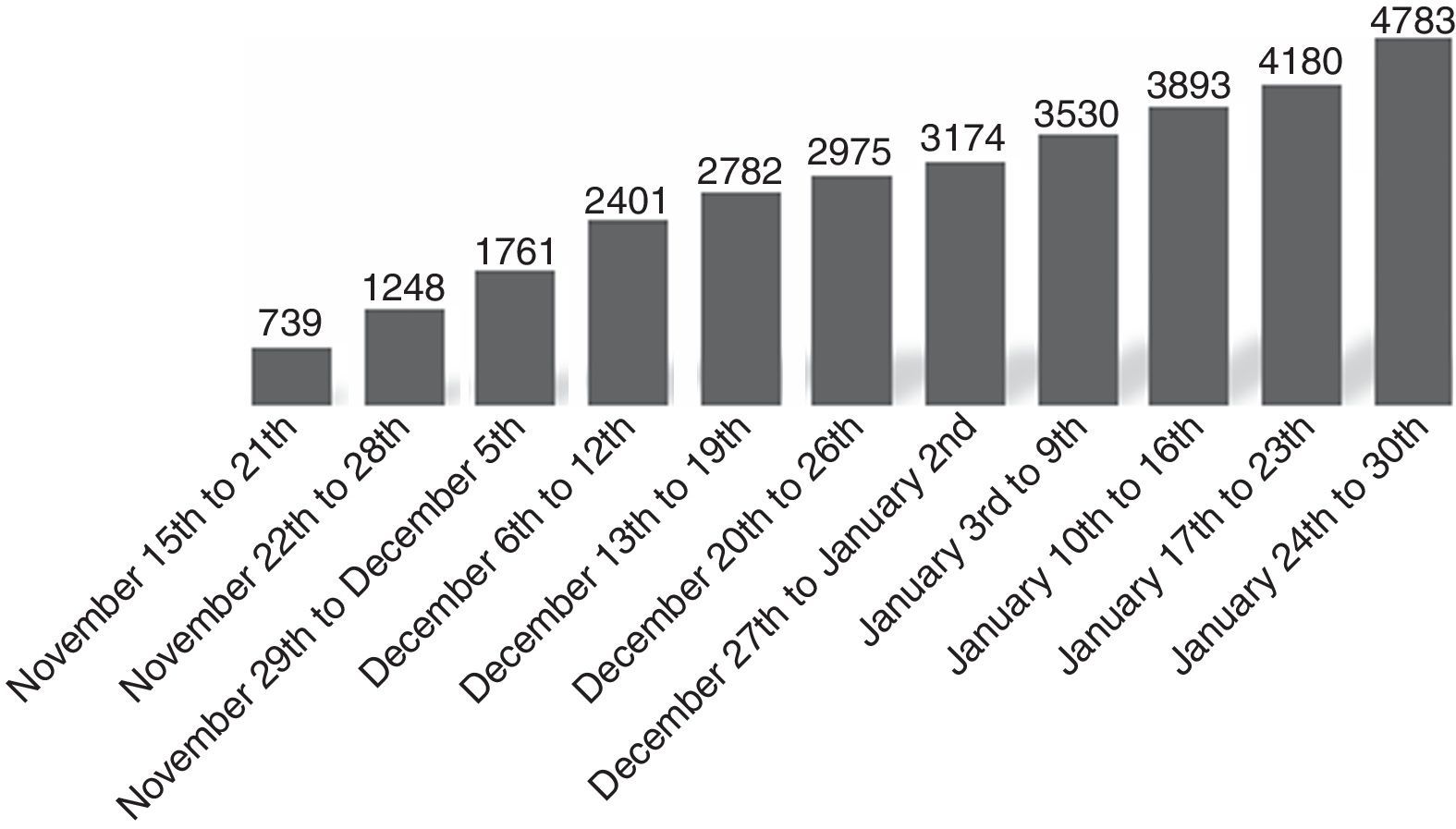

Currently, due to the progressive extension of cases of microcephaly, corresponding to 4783 suspected and 404 confirmed cases,6 this situation became extremely concerning to public health, since only 18% of the infected are symptomatic4 and there is no treatment for this condition.7 Therefore, the control of pregnant women who might bear a child with microcephaly is impaired, and consequently, a strict monitoring during prenatal care is needed.

In view of this new and alarming scenery, this study aimed to conduct a literature review about ZIKV and microcephaly, evaluate epidemiological data published until February 5th 2016 in national and international levels, as well as to review the current recommendations for the health teams.

Zika virusThe ZIKV is an arbovirus (arthropod-born virus), since part of its reproductive cycle occurs within the body of hematophagous insets. They belong to the Flaviviridae family, and Flavivirus genus, whose members are composed by a protein capsid involved by a lipid envelope, in which the membrane protein and glycoprotein spikes are inserted. The Aedes sp. mosquitoes are the vectors responsible for transmitting this microorganism, as well as Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV), and West Nile fever virus (WNV).8

The ZIKV was initially isolated in a Rhesus monkey, at the African Zika forest in Uganda. In the 60s, the first cases of ZIKV infection in humans have been confirmed by serologic evidence in the countries of Uganda, Nigeria, and Senegal.9 The dissemination was so great that in 2007 the first outbreak outside Africa and Asia was reported, on the Yap Island (Federated States of Micronesia). In October of 2013, the largest ZIKV outbreak affected approximately 28,000 inhabitants of the French Polynesia.8 After two years, in May 2015 the Brazilian MOH issued a statement confirming the first cases identified in the country: 16 people in the Northeast, at Bahia and Rio Grande do Norte states, were tested positive for the virus.4

The condition of ZIKV infection is named “dengue-like syndrome” because it resembles an infection caused by the DENV.9 The clinical criteria for diagnosing this self-limited disease are pruritic maculopapular rash plus at least two of the following: fever (generally low grade fever lasting 1–2 days), non-purulent conjunctivitis, polyarthralgia, and periarticular swelling.10 Other signs and symptoms may be present, such as muscle pain, retroocular pain, vomiting, and lymph node hypertrophy.9 Besides, ZIKV infection can affect the central nervous system (CNS). There are reports of a 20-fold increase in the incidence of Guillain–Barre Syndrome (GBS) in Micronesia during the outbreak of ZIKV, in addition to cases of GBS after infection by this pathogen in French Polynesia.11 However, about 80% of infections are asymptomatic, what makes the diagnosis and prevention of transmission highly challenging.12

The detection of viral RNA in the acute phase – up to 10 days from onset of symptoms – by RT-PCR assay is the method of choice for identification of the virus so far. Fortunately, studies to improve the identification of immunoglobulin (IgM) by ELISA are being carried out, but cross-reaction with the DENV is likely to occur in endemic areas of dengue fever.5,13 Moreover, another study suggested the possibility of diagnosing the infection from urine samples. Viral RNA was isolated even after 10 days of onset of symptoms, which shows that this technique is suitable for later diagnosis when compared with tests using blood samples.14

TransmissionZIKV is mainly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti vector, which resides in tropical and subtropical regions, as well as by the Aedes albopictus, inhabitant of the European Mediterranean. After the mosquito's bite, there is an incubation period of about nine days, and then the symptoms ensue.15,16

Although there is no evidence of sexual transmission in humans by other arboviruses, some authors hypothesized that this could be possible for ZIKV. Patients exposed to endemic areas showed symptoms of the disease and one atypical signal of hematospermia. In such cases, the presence of virus in semen was confirmed by serological tests or by RT-PCR. In addition, one of the sexual partners of these patients had similar symptoms, strengthening this assumption.8,16

During the outbreak in French Polynesia, a study to investigate ZIKV in blood donors was carried out using RT-PCR modified technique. It was noted that 3% of donors were asymptomatic hosts of the virus, but no case of infection was identified after blood transfusion. Still, the results suggest that testing for ZIKV must be implemented in the routine of blood donation.15,17

Regarding perinatal transmission, which is the main focus of this review article, on November 17th 2015 investigators of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (OCI/Fiocruz) detected the presence of ZIKV genome in amniotic fluid samples of two pregnant women in the state of Paraiba (Northeast), in whom ultrasound exams had confirmed microcephalic fetuses.18 This fact taken in isolation does not confirm transplacental transmission of the virus but is highly suggestive, since most of the pathogens that cause infections in pregnancy, such as toxoplasmosis, can be detected in the amniotic fluid.19

At the same time, the French Polynesian authorities reported a significant increase in cases of CNS malformations in fetuses born between 2014 and 2015, which was the period of ZIKV outbreak in the region.20 In this nation, a study20 suggests that other forms of contagion, such as milk and saliva, ought to be considered. This was evidenced in cases in which RT-PCR was positive for ZIKV in mother's milk, and baby's and mother's saliva, but when inoculated in Vero cells the viruses did not replicate. However, since this kind of transmission can occur in other arboviral diseases, like dengue21 and West Nile fever,22 these possibilities of contamination should not be neglected.

One of the concerns about the infection in women is the virus latency period, because it is not known if a virus acquired in a non-pregnant woman could have a potential impact on a future fetus. That is why some protocols highlight the importance of also notifying cases in which women have experienced symptoms 40 days before pregnancy.23

MicrocephalyMicrocephaly is defined as the measurement of head occipto-frontal circumference being more than two standard deviations below the mean for age and gender.24 It is known that the brain of microcephalic patients is proportionally smaller, thus about 90% of the cases are associated with some degree of intellectual disability.5 It is important to remind that microcephaly is not a diagnosis but a clinical finding, therefore further investigation is necessary when facing this situation.25

Regarding the initiation, microcephaly can be classified as primary (congenital) or secondary (postnatal). Primary microcephaly can be detected before 36 weeks of gestation. This may occur by failure or reduction of neurogenesis, by destructive pre-natal insults or by very early degenerative processes.25 The secondary microcephaly is caused by any insult factor in the development and function of the CNS. It associates commonly with neurological disorders.25

The etiological approach of microcephaly is extensive, as this can be caused by many genetic, environmental, and maternal factors.5 Not infrequently, genetic microcephaly progresses with dysmorphic features or concomitantly with other congenital abnormalities and it is very common the association with syndromes, as in Down Syndrome.5,25,26 As for environmental and maternal factors, there are hypoxic ischemic insults, placental insufficiency, systemic and metabolic disorders, exposure to teratogens during pregnancy, pregnant women with severe malnutrition, maternal phenylketonuria, and CNS infections (such as rubella, congenital toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus infection, herpes, and HIV).5,25 However, in some cases, the etiology of microcephaly cannot be defined (idiopathic).25

Concomitantly with the increase in cases of microcephaly notified by MOH, there was an outbreak of ZIKV infection, which was listed as a possible cause of that malformation.20 According to information reported by the Brazilian live births information system (SINASC), the extension of the 2015 situation becomes even more significant compared to previous years. From 2010 to 2014 there were around 150 cases reported per year in the country, and currently, suspected cases totaled 4783.6,27 Six months have elapsed between the first virus transmission reports (May 2015) and microcephaly outbreak (November 2015), which is the appropriated time for diagnosing cranial abnormalities by prenatal ultrasound examination, suggesting a temporal correlation. The increase in cases of microcephaly occurred in the same area where there had been circulation of virus, indicating also a place correspondence.27

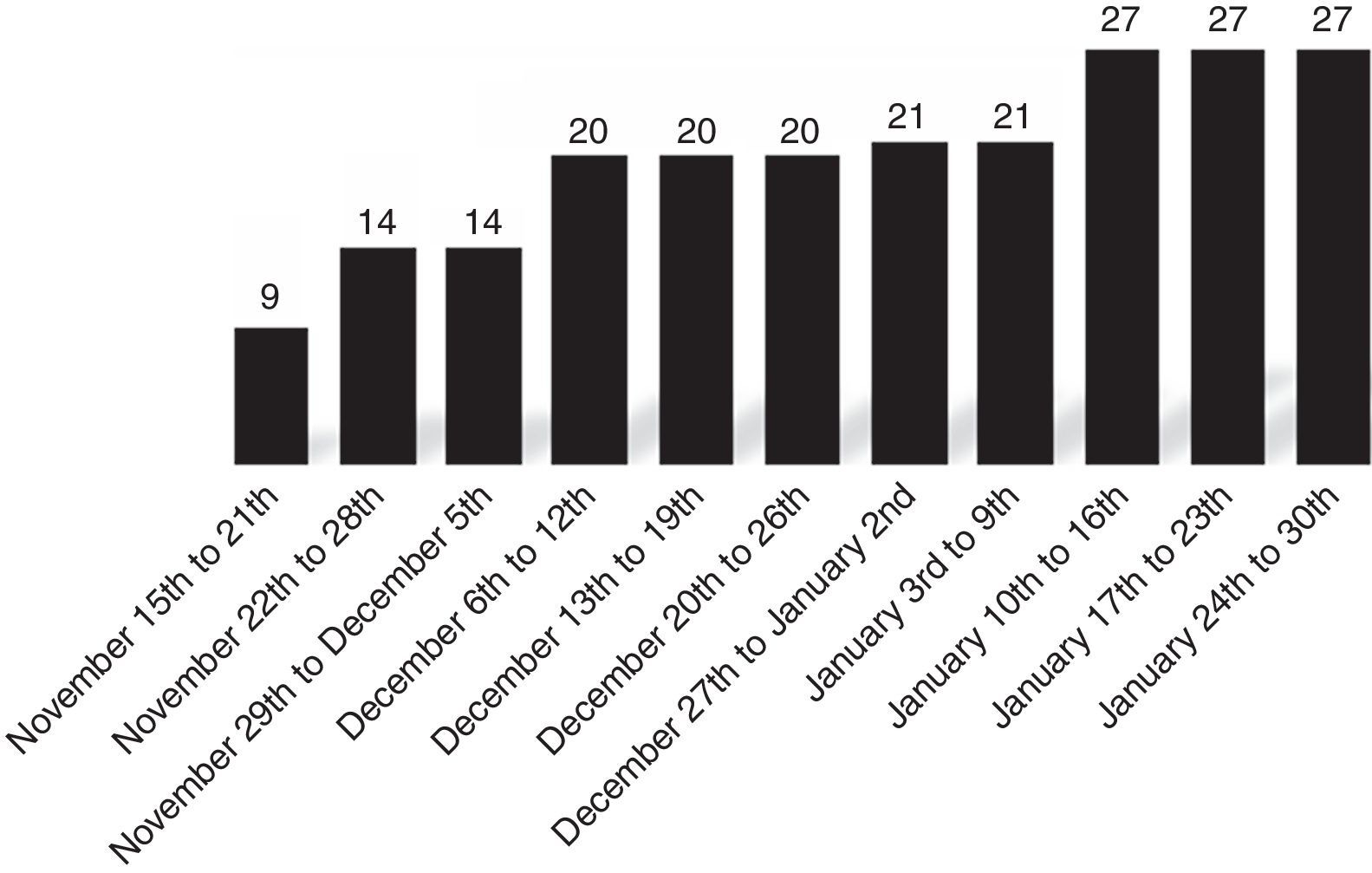

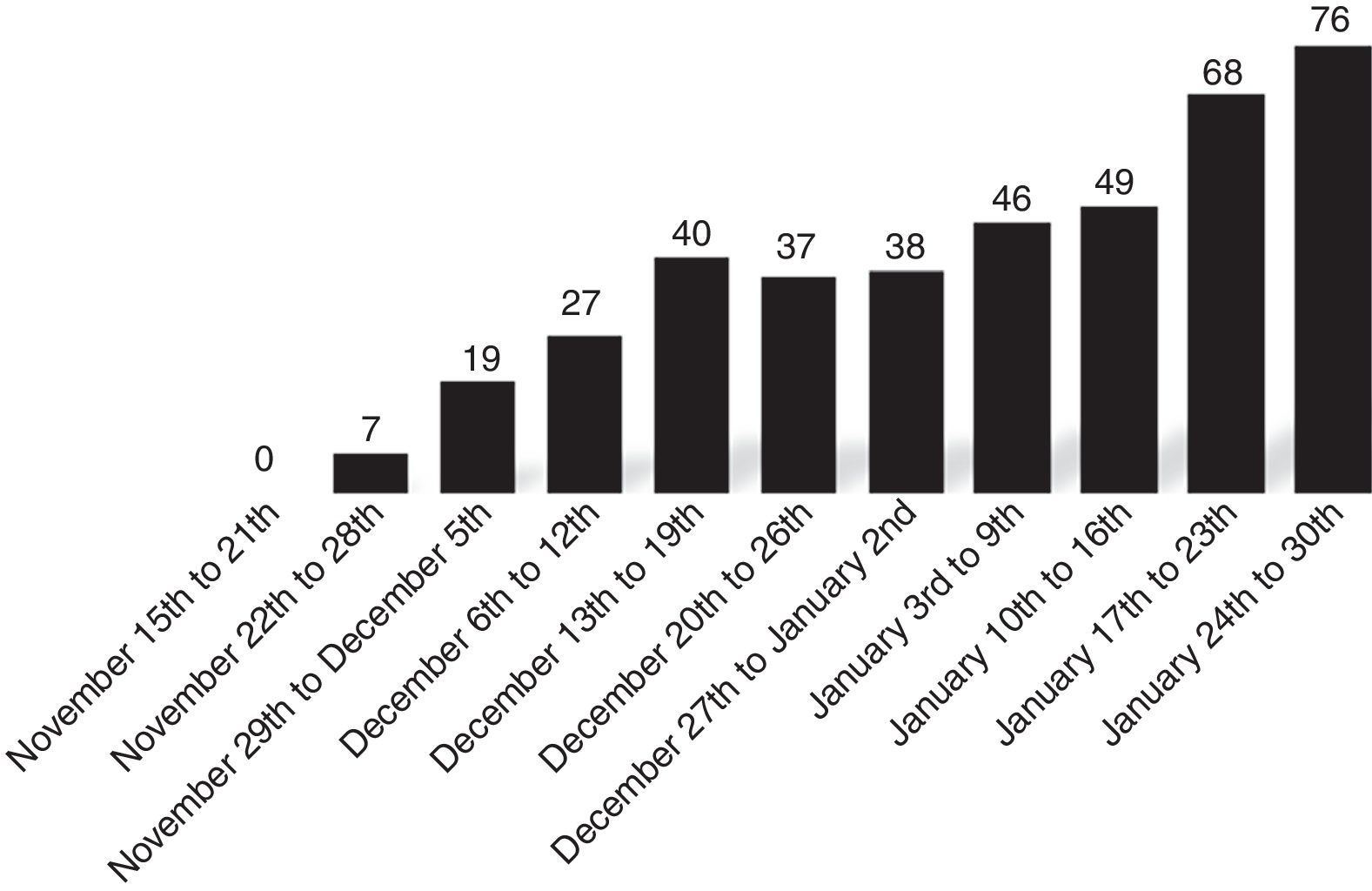

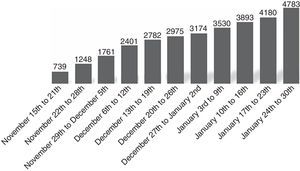

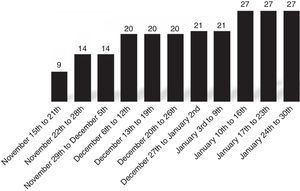

As a result of the increasing impact of this scenery, the MOH deployed the Emergency Operations Center on Health Issues (COES) on November 10th 2015, and after one day, declared “Public Health Emergency of National Importance”.28 The COES weekly publishes epidemiological reports, making it possible to compare and observe a large growth in the number of suspected cases of microcephaly (Fig. 1), and also the progressive involvement of other Brazilian states in different regional areas (Figs. 2 and 3). Of the total of suspected cases, 3670 are under investigation, 404 have been confirmed, and 704 were discarded from surveillance.6

Suspected cases of microcephaly. Graph showing the progressive prevalence of suspected cases of microcephaly occurring in Brazil from the beginning of the Zika virus outbreak until January 30, 2016.6,29–38

Affected federal units. Graph showing the progressive prevalence of suspected cases of microcephaly according to the number of Brazilian states, or Federal units, affected from the beginning of the Zika virus outbreak until January 30, 2016.6,29–38

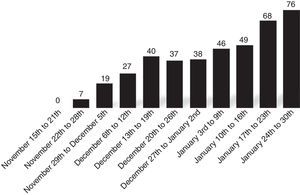

Suspected deaths. Graph exhibiting the progressive prevalence of suspected deaths related with microcephaly caused by the ZIKV occurring in Brazil from the beginning of the outbreak until January 30, 2016.6,29–38

Scientific evidence support the relation between ZIKV infection and microcephaly. The literature describes neurotropism as a characteristic of ZIKV in laboratory tests involving rats.39 This fact endorses the hypothesis that the virus directly acts on nerve cells of the fetus. Yet, another possibility is that the mechanism occurs through the immune system, such as in Guillain–Barre condition, where antibodies are formed against neuronal myelin sheath.40

Different arboviruses have also shown neurological consequences in perinatal infections, such as encephalopathy by CHIKV in humans41 and necrotizing encephalopathy and white matter vacuolization by the Akabane virus in sheep and goats.42 In addition, arboviruses can cause meningitis, myelitis, neuritis, producing symptoms such as headache, fever, vomiting, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, and even Parkinsonism and chronic epilepsy.43

Other facts also corroborate this association. In November 2015, the Evandro Chagas Institute declared the presence of ZIKV genome in blood and tissues of a baby with microcephaly, who died 5min after birth.1,20 Likewise, according to the epidemiological reports of COES, the number of deaths assumed to be associated with this deformity has expanded significantly since this case. Among the 76 suspected cases, 15 were confirmed.6

Furthermore, analysis of medical records and interviews with 60 women, who presented a rash during their pregnancy and whose babies were born with microcephaly, showed an absence of other genetic disorders in the family and of findings that might suggest others infections. Thus, the exanthematous disease is probably the putative cause of this deformity.44

In spite of the relation between microcephaly and ZIKV infection being established in Brazil, some epidemic countries, such as Micronesia and New Calendonia, showed no raise in the number of congenital CNS deformities. It is worth remembering that, however, such sites have considerably smaller population as well as less registered cases, making their limited sample difficult to analyze.27

The microcephaly is an anomaly in which the skull growth is limited due to the lack of stimulation as a result of the deficit in the brain growth.45 The first trimester of pregnancy is when there is greatest risk that some external factor would cause malformations in the developing child. But when it comes to the CNS, the risk exists throughout pregnancy.5 According to analyses carried out in Brazil, the risk of microcephaly or congenital abnormalities in newborns associated with ZIKV is greater when the infection occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy.20,27 Health authorities of French Polynesia suggested that the critical interval would be during the first or second trimesters.20,27 Nevertheless, the gestational period of major vulnerability remains unknown.

Moreover, it has been suggested that microcephaly related to ZIKV could be more aggressive. According to a research with a cohort of 35 babies that were born with microcephaly in Brazilian affected areas, 71% of them had this abnormality in a severe level.46 Consequently, depending on the intensity, it could lead to seizures, hearing and vision impairment, intellectual disability, developmental impairment, and even a life-threatening condition.47

Detecting, monitoring and managingWhereas ZIKV infection became a public health emergency, the Brazilian MOH and several state health departments have published protocols, reports and notes concerning the diagnosis and management of congenital microcephaly. As it is a recent condition, there is still much controversy about guidelines and dynamic flowcharts. For this part of the review, we selected technical reports of State Departments of Health (SESA) of two states considered of great importance in this epidemiological situation: São Paulo and Pernambuco, in addition to the MOH protocols.

The MOH published the “Surveillance Protocol in Response to the Occurrence of Microcephaly related to the ZIKV Infection”. This document advises that the presence of exanthema in a pregnant woman, regardless of gestational age, features a suspected case of Zika virus infection, after ruling out other infectious and non-infectious causes. The confirmation is made by a specific positive laboratory test for the pathogen. The MOH recommends two blood samples of the pregnant woman under investigation: the first collected three to five days after the onset of symptoms and the second two to four weeks after the first sample. The material will only be analyzed by PCR if the serology is positive. The ZIKV-specific IgM antibodies can be detected by ELISA or immunofluorescence assays in serum specimens from day five after the onset of symptoms. However, there are no commercial kits for serological diagnosis of ZIKV.44,48

The management of pregnant women with suspicion of ZIKV infection differs slightly between the SESA of Pernambuco, the SESA of Sao Paulo, and recommendations by the MOH. According to the SESA of Pernambuco, it is necessary to collect a blood sample within five days of the onset of symptoms and a urine sample within eight days, then repeat blood sampling 14–21 days after the start of clinical symptoms. These samples will be analyzed by serology and molecular biology for ZIKV. Still, for this group of pregnant women it is recommended an ultrasound examination between the 32 and 35 weeks of gestation regardless of laboratory test results.5 For the São Paulo SESA, the only difference from the MOH recommendations is that the second blood drawing should be done 3–4 weeks after the onset of symptoms.49

For the pregnant women with no history of skin rash and who gave birth to a child with microcephaly, the MOH recommends collecting a mother's blood sample at the time of diagnosis of the child's malformation, and a second blood collection 2–4 weeks after the first sample.44 The report of São Paulo State determines that the second test should be done 3–4 weeks after the first collection,49 while Pernambuco's Protocol does not specify about this lay-off.5

The diagnosis of microcephaly can be made during the prenatal and/or postnatal periods. According to the MOH recommendations a case should deemed suspected during pregnancy when the fetus presents head circumference (HC) with two standard deviations below the mean for gestational age or when there is an ultrasound finding with CNS alteration suggestive of congenital infection. Any suspected case of microcephaly caused by ZIKV should be immediately notified to health authorities. In order to confirm, it is necessary to rule out other infectious and non-infectious causes or perform laboratory tests.44 The Pernambuco's Protocol propose that, if there is positivity in these tests, the health professional must issue a notification to the local health authorities, explain the ultrasound findings to the mother, evaluate the need for repeating the ultrasound, keep prenatal care routine – as isolated microcephaly does not characterize pregnancy as high risk – and guide the pregnant woman to psychosocial support by a multidisciplinary team of the health unit.5 The São Paulo SESA does not specify the correct approach to a case of microcephaly during prenatal care.49

On the other hand, the postnatal diagnosis used to be determined by the cutoff of HC value lower or equal to 33cm. But recently the MOH decreased this number to less than or equal to 32cm, the same value proposed by the WHO, consequently avoiding unnecessary exposure to potentially harmful tests in children with normal skull. When the HC of the newborn is below the third percentile or less than or equal to 32cm, it is considered a suspected case associated with ZIKV infection, and it is confirmed through positive samples for the virus in the newborn or in the mother during pregnancy. Babies with congenital microcephaly should have samples of blood, umbilical cord, cerebrospinal fluid, and placenta collected at birth and analyzed by ZIKV serology, which, if positive, should be further subjected to molecular biology analysis.44 The preferred imaging exam is transfontanellar ultrasonography (US-TF) in order to avoid exposure to computed tomography scan (CT-scan). For those babies who present early-closing fontanel or if the suspicion persists after diagnostic laboratory and imaging tests, cranial CT-scan without contrast should be performed.50 However, the São Paulo SESA recommends the execution of laboratory tests involving merely the umbilical cord, placenta, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).49 On the other hand, the Pernambuco SESA advise that only CSF and blood of the fetus and the mother's blood should be tested, and the first imaging evaluation to be done is cranial CT scan without contrast.5

As stated, suspected and confirmed cases of microcephaly related to ZIKV infection must be notified. The notification shall be recorded in the online form of Public Health Event Log (RESP-Microcefalias), available on www.resp.saude.gov.br and SINASC online system. This is extremely important for epidemiological understanding of the features of this viral infection, since this data will be stored in a governmental database.44

The MOH endures the operation of nonspecific laboratory tests for newborns with microcephaly, which are: complete blood count, serum levels of liver aminotransferases, direct and indirect bilirubin, urea, creatinine, and indicators of inflammatory activity, as well as an abdominal ultrasound and echocardiography.44 The Pernambuco SESA also recommends rapid test for syphilis and/or VDRL.5 The technical report of the State of São Paulo does not specify which laboratory tests must be made in the newborn.49

Additionally, as microcephaly may be related to neurodevelopmental disorders, the Auditory Evoked Potential testing (BAEP) should be performed as the first choice for hearing assessment, in addition to the Ocular Neonatal Screening Test, for ophthalmic evaluation, and the Biological Newborn Screening Test.50 The São Paulo SESA does not specify any of these tests,49 while Pernambuco SESA emphasizes the importance of ophthalmologic examination with fundoscopy in newborns with microcephaly.5

A case of stillbirth with microcephaly at any gestational age is deemed suspected if the mother had a history of rash illness during pregnancy. Any suspected cases must be reported, and should undergo confirmation tests for ZIKV identification in the mother or fetal tissue. For this purpose, the MOH recommends collecting samples of 1cm3 from the child's organs (brain, liver, heart, lung, kidney and spleen) and 3cm3 from the placenta for molecular and immunohistochemistry biology tests, in addition to the serological evaluation of the mother.44 In regard to this detection, the Pernambuco's Protocol also recommends that baby's tissue samples and placenta should be collected but it does not mention the mother's serum testing,5 while the São Paulo SESA has no recommendation on stillbirths in its technical report.49

In case of a positive history for rash during pregnancy followed by an abortion, the MOH considers it as a suspected abortion related to ZIKV infection. It is confirmed only when the pathogen is identified in maternal or fetal tissue. Therefore, it is necessary to collect samples in the same way as for the cases of stillbirths with ZIKV related microcephaly.44 The São Paulo and Pernambuco SESA have not published recommendations for this situation.5,49

The most effective plan to combat this outbreak of microcephaly possibly caused by ZIKV is the prevention, fighting the Aedes sp. mosquito by eradicating their breeding grounds.51 It is essential for the community to be oriented on the control of mosquito proliferation in urban and peri-urban areas. For this reason, public health actions, such as home visits by health professionals, advising and guiding the population to eliminate vector sources inside the houses should be implemented. Additionally, using insecticides sprayed by vehicles on public roads and urban sanitation campaigns should be contemplated.44,52

The MOH endorses instructing fertile women, who wish to have a child, about the current situation of microcephaly in the country.5,50 Health authorities do not request to postpone pregnancy, although there is discussion regarding this subject, especially for young couples who could plan for pregnancy after best knowledge and control of this virus. It is important for healthcare professionals to inform the population in general about the disease, belying unofficial information and checking the official data from epidemiological bulletins released weekly (available in www.saude.gov.br/sus). Moreover, it is particularly important to make an early diagnosis of microcephaly and recognize possible brain dysfunctions to guide the patient to a healthcare unit that can implement early brain stimulation measures.50

Furthermore, for personal protection, mainly for pregnant women, the MOH suggests using topical repellent products, registered at the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA). It is important to instruct the patients to follow the recommendations on the label and to spray insect repellent on top of the clothing. Researches demonstrate safety of n-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET)-based repellents. Nonetheless, other substances are also used in Brazil, such as hydroxyethyl isobutyl piperidine carboxylate (icaridin or picaridin) and ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535 or EBAAP), and essential oils such as citronella. Even if these products are safe for regular use, there are no studies in pregnant women. The CDC informs that repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, some oil of lemon eucalyptus and para-menthane-diol products provide long lasting protection.44,53

Besides repellent topical use, other forms of prevention are also important. It is suggested, whenever possible, the use of long clothes to protect the largest body surface as possible against mosquito's bites. Places and times with the presence of mosquitoes should be avoided, consequently it is important to stay in locations with barriers against the entry of insects, mainly in the period between sunset and dawn, as protective screens, mosquito nets, and air conditioning.44,50

In case of any alteration in the health condition of pregnant women, especially until the fourth month of pregnancy, it should be reported for the health professional.51 It is important to posit that defects in the CNS may also be caused by other conditions and diseases, such as toxoplasmosis, rubella, abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs during pregnancy, and also genetic syndromes that make differential diagnosis with those conditions associated with ZIKV.5

ConclusionThe relation between ZIKV infection during pregnancy and microcephaly in neonates was established by the Brazilian MOH. Therefore, more attention regarding Aedes sp. is required, since it transmits this disease, which has more disastrous consequences than DENV infection. Also, the pregnant woman should be concerned about exposure to endemic areas, and if possible, avoid remaining in such locations. Since there is still no evidence about the period of vulnerability of the embryo's development, the protection by using repellents in an epidemic situation is crucial throughout pregnancy. Notably, it is worth emphasizing that more research is warranted to study viral mechanisms of action on newborns and in their development, because although microcephaly can be easily diagnosed in the delivery room, other possible damage to the fetus can be not so evident.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.