Streptococcus bovis is a classical etiology of endocarditis and is associated with colonic lesions. No series of cases from Brazil has been described.

ObjectivesTo describe aspects of S. bovis endocarditis.

MethodsThis is a case series of patients admitted to a cardiac surgery referral center, during the years 2005–2014. Clinical, laboratory, echochardiographic, colonoscopic, treatment, surgical and outcome variables were studied.

ResultsNine patients with S. bovis endocarditis were included; all cases fulfilled the modified Duke criteria. Incidence was 8/220 (4%) in years 2006–2014. There were seven male and two female patients; mean age was 56.7 years, standard deviation 13.4. All patients had native aortic valve involvement. Presentation was subacute in 7/9 (71%). Fever was present in 7/9 (77.7%), embolic lesions to solid organs occurred in three, and perivalvular abscess in two patients. All echocardiograms showed moderate to severe valvular regurgitation and vegetations. Microcytic anemia was seen in 7/7 patients. Colonoscopy showed abnormal findings in 7/9 (77.7%). Surgery was indicated for 6/9 patients due to acute aortic regurgitation and left ventricular failure. All patients were discharged home.

ConclusionsS. bovis most frequently affected the aortic valve of male patients. Colon disease was frequent. Surgery was indicated frequently due to hemodynamic compromise.

S. bovis endocarditis is a classical, but uncommon cause of infective endocarditis (IE). The association of S. bovis IE and colon carcinoma has long been established. Several other colonic, non-neoplastic conditions have been attributed to S. bovis such as adenomatous polyps, hyperplastic polyps and diverticular disease, adenomatous polyps predominating, corresponding to 53% of cases.1 These evidences have established the need to investigate colon or liver disease in all patients presenting with S. bovis bacteremia and/or endocarditis. S. bovis bacteremia is a major criterion for infective endocarditis2 and echocardiograms are mandatory in this clinical scenario.

Recent studies have suggested a new nomenclature for S. bovis, so that S. bovis biotype I is now named Streptococcus gallolyticus, biotype II.1 corresponds to Streptococcus infantarius, and biotype II.2 to Streptococcus pasteurianus. In this respect, the “S. bovis” most commonly associated with colonic cancer is currently identified as S. gallolyticus biotype I; this is the species usually isolated from blood cultures in this situation.3 However, the routine clinical microbiology laboratory still reports “S. bovis” only.

A large case series evaluating 2781 cases of definite IE in adults, from various sites, in the International Collaboration Study on Infective Endocarditis-prospective cohort study, in the years 2000–2005, has shown geographical differences between the incidence of S. bovis IE.4 It corresponded to 9/597 (2%) of cases in North America, 17/254 (7%) in South America, 116/1213 (10%) of cases in Europe, and 23/717 (3%) of cases in other sites (Africa, Middle East, Asia). Despite the reference to 13 cases of S. bovis IE in 300 (4.3%) Brazilian patients with IE in a series published in 1990, no analysis of this group of patients was provided.5 Two recent Brazilian series of IE with 62 and 64 cases, respectively, did not feature S. bovis as an etiologic agent.6,7 The goal of the present study was to describe the features of a series of cases of IE in a Brazilian scenario, establishing a comparison to what is known from the literature.

This is a prospective case series study of patients admitted to Instituto Nacional de Cardiologia (INC), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between the years of 2005 and 2014. Adult patients with definite IE, according to the modified Duke criteria8 were included. INC is a cardiac surgery referral hospital, receiving a large number of cases with IE who have an indication for surgery. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of INC under the number 080/2005. Informed consent was obtained for all patients. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

Incidence of S. bovis IE was determined, as well as demographic data, clinical presentation, affected valves, routine laboratory and echocardiographic data, complications, presence of comorbidities, associated liver or colonic disease, surgery and mortality. Identification of S. bovis was done by automated methods (VITEK II system) and no biotyping was available. Descriptive statistics, using frequencies as percentages and mean and standard deviation (SD) was computed on Excel® charts.

Nine cases of S. bovis IE were seen in the study period (2005–2014). All cases were referred from other hospitals. There were seven male and two female patients; age range was 26–70 years, mean±SD was 56.7±13.4 years. All patients presented aortic valve involvement, although two also had the mitral valve affected and one the tricuspid valve. Clinical presentation was subacute in 7/9 patients and acute in 2/9.

In the past medical history, three patients had previous abdominal surgery, two had chronic liver disease, three had previous IE, two had congestive heart failure, and two had a history of rheumatic fever. One out of six was a heavy drinker, three drank “socially”; one was a smoker. Three of the nine patients already had a previous diagnosis of colon carcinoma (four, five and six years prior to the present episode of IE).

Fever was seen in 7/9 (77.7%), newly diagnosed splenomegaly in two out of six patients (33.3%). Embolic phenomena were seen in 3/9 patients (splenic infarct in one, splenic abscess in two). Two of nine patients had intracardiac abscesses. No patients had persistently positive blood cultures, persistent sepsis, or osteoarticular complications.

C-reactive protein levels were elevated in 3/7 cases (42.8%) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in four (57%, 4/7). Ferritin levels were within normal range in the eight cases in whom it was measured, although hemoglobin level was low in all 7/7 patients who it determined. Mean hemoglobin was 10.22 and mean corpuscular volume was 77.6fl.

Transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) were done in two patients and transesophageal scans in seven; moderate to severe valvular regurgitation and vegetations were seen in all scans. Major echocardiographic criteria were present in all patients, two by TTE and seven by TEE.

All patients were submitted to colonoscopy, and 7/9 (78%) had abnormal findings: three colon carcinomas, four diverticular disease of the colon (polyps were present in three of these).

Antibiotic treatment was given for four to six weeks, and consisted of penicillin in 5/9 cases, and ampicillin in 4/9; gentamicin was given in combination in six cases.

Surgery was indicated in 6/9 cases due to severe aortic regurgitation and/or heart failure.

All patients were discharged alive from the index hospitalization.

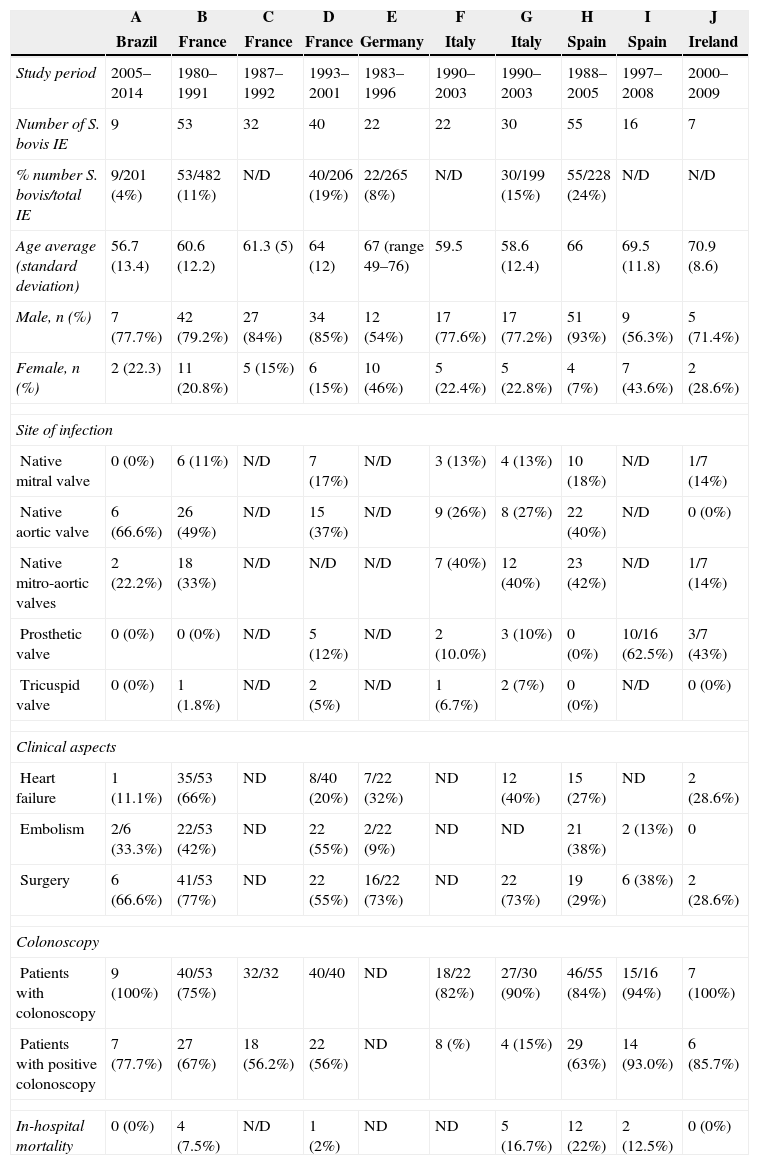

Table 1 summarizes the main clinical and laboratory characteristics of the cases, and compares them to other published series. Papers selected for comparison were those reporting series of patients with S. bovis IE after the 1980s.

Comparison of variables from recent case series of S. bovis infective endocarditis.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | France | France | France | Germany | Italy | Italy | Spain | Spain | Ireland | |

| Study period | 2005–2014 | 1980–1991 | 1987–1992 | 1993–2001 | 1983–1996 | 1990–2003 | 1990–2003 | 1988–2005 | 1997–2008 | 2000–2009 |

| Number of S. bovis IE | 9 | 53 | 32 | 40 | 22 | 22 | 30 | 55 | 16 | 7 |

| % number S. bovis/total IE | 9/201 (4%) | 53/482 (11%) | N/D | 40/206 (19%) | 22/265 (8%) | N/D | 30/199 (15%) | 55/228 (24%) | N/D | N/D |

| Age average (standard deviation) | 56.7 (13.4) | 60.6 (12.2) | 61.3 (5) | 64 (12) | 67 (range 49–76) | 59.5 | 58.6 (12.4) | 66 | 69.5 (11.8) | 70.9 (8.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 7 (77.7%) | 42 (79.2%) | 27 (84%) | 34 (85%) | 12 (54%) | 17 (77.6%) | 17 (77.2%) | 51 (93%) | 9 (56.3%) | 5 (71.4%) |

| Female, n (%) | 2 (22.3) | 11 (20.8%) | 5 (15%) | 6 (15%) | 10 (46%) | 5 (22.4%) | 5 (22.8%) | 4 (7%) | 7 (43.6%) | 2 (28.6%) |

| Site of infection | ||||||||||

| Native mitral valve | 0 (0%) | 6 (11%) | N/D | 7 (17%) | N/D | 3 (13%) | 4 (13%) | 10 (18%) | N/D | 1/7 (14%) |

| Native aortic valve | 6 (66.6%) | 26 (49%) | N/D | 15 (37%) | N/D | 9 (26%) | 8 (27%) | 22 (40%) | N/D | 0 (0%) |

| Native mitro-aortic valves | 2 (22.2%) | 18 (33%) | N/D | N/D | N/D | 7 (40%) | 12 (40%) | 23 (42%) | N/D | 1/7 (14%) |

| Prosthetic valve | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | N/D | 5 (12%) | N/D | 2 (10.0%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 10/16 (62.5%) | 3/7 (43%) |

| Tricuspid valve | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | N/D | 2 (5%) | N/D | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | N/D | 0 (0%) |

| Clinical aspects | ||||||||||

| Heart failure | 1 (11.1%) | 35/53 (66%) | ND | 8/40 (20%) | 7/22 (32%) | ND | 12 (40%) | 15 (27%) | ND | 2 (28.6%) |

| Embolism | 2/6 (33.3%) | 22/53 (42%) | ND | 22 (55%) | 2/22 (9%) | ND | ND | 21 (38%) | 2 (13%) | 0 |

| Surgery | 6 (66.6%) | 41/53 (77%) | ND | 22 (55%) | 16/22 (73%) | ND | 22 (73%) | 19 (29%) | 6 (38%) | 2 (28.6%) |

| Colonoscopy | ||||||||||

| Patients with colonoscopy | 9 (100%) | 40/53 (75%) | 32/32 | 40/40 | ND | 18/22 (82%) | 27/30 (90%) | 46/55 (84%) | 15/16 (94%) | 7 (100%) |

| Patients with positive colonoscopy | 7 (77.7%) | 27 (67%) | 18 (56.2%) | 22 (56%) | ND | 8 (%) | 4 (15%) | 29 (63%) | 14 (93.0%) | 6 (85.7%) |

| In-hospital mortality | 0 (0%) | 4 (7.5%) | N/D | 1 (2%) | ND | ND | 5 (16.7%) | 12 (22%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

A – present study, adapted from references: B – Ballet et al. (1995); C – Bruno Hoen et al. (1994); D – Pergola et al. (2001); E – Kupferwasser et al. (1998); F – Tripodi et al. (2005); G – Tripodi et al. (2004); H – Corredoira et al. (2008); I – Fernández-Ruiz et al. (2010); J – Fitzmauric et al. (2013).

S. bovis group colonizes the human gastrointestinal tract. It is present in 2.5–15% of healthy individuals and in 29–55% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and colon carcinoma. It reaches the bloodstream by penetrating the gastrointestinal mucosa, which is facilitated by breaches as in inflammation or neoplasia. S. bovis group accounts for approximately 7% of native valve IE in non-drug users and 5% in patients with prosthetic valve IE in the largest published series so far.4 However, the incidence of S. bovis IE varies greatly by geographical area, in this same report. All major series of IE reported so far are from Europe, where incidence is above 10%.9–17 Although S. bovis features in some series of IE from Brazil, it has not been studied as a single entity, so as to verify differences or similarities to the literature.

IE in Brazil, a developing country, affects both young patients, with rheumatic heart valve disease, and older patients, who may have underlying colonic pathology. In our institution, incidence of S. bovis IE was 4% in recent years, which is similar to a recently published series of IE.18 This may reflect the low positivity rates of blood cultures, especially because of prior antibiotic use. In Brazil, purchase of antibiotics was restricted to medical prescription only after 2011, and over-the-counter sale of antibiotics was the rule until then. Antibiotic use would rapidly clear S. bovis from the bloodstream, as it is very sensitive to penicillin.6,7,19

S. bovis IE usually affects patients older than 60 years; mean age in our study was 56.7 years. It more often affects the aortic valve, and this was the case in all our patients, although there is a referral bias, since INC is a surgical hospital and hemodynamic compromise is more severe when the aortic valve is affected. However, aortic valve involvement, alone or combined with the mitral valve, with high rates (55–77%) of surgery indication was seen in larger series from France, Italy and Germany.9–12 A strong association with colonic cancer has been recognized for S. bovis biotype I, or S. gallolyticus.20 However, colonic lesions found in association with S. bovis IE may be neoplastic or non-neoplastic. It is believed the colonic lesion facilitates colonization by S. bovis, provides a physical breach in the mucosa, and therefore makes bacteremia more likely. On the other hand, S. bovis may have tumor promoting properties to colonic lesions, via proinflammatory (cyclo-oxygenase 2) pathways. Incidence of colon carcinoma and IE by S. bovis has been estimated as 18–62%, and it was present in three out of nine patients in this series. Bacteremia or endocarditis may precede or follow colon carcinoma. Three of the nine patients in our study already had a previous diagnosis of colonic cancer.

A recent meta-analysis was conducted to determine the risk associated with Streptococcus bovis infection and the occurrence of colorectal neoplasia.21 Studies included were those on S. bovis septicemia, S. bovis endocarditis and S. bovis fecal carriage. Overall, the presence of S. bovis infection was found to be significantly associated with the presence of colorectal neoplasia. S. bovis endocarditis showed the strongest association in analyses of case-control studies and case series (OR 14.54, 95% CI 5.66–37.35).

Despite the small number of cases in this series, it is the first series of S. bovis IE describing patients from Latin America. The clinical profile of S. bovis IE and associated colon disease was similar to other recently published series from Europe. Similarities are the mean age of 60 years, the predominance of aortic valve involvement, high proportion of surgery indication, and the finding of colonic pathology in most patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank all the medical and non-medical staff who helped looking after the patients presented in this study.

Dr. Lamas thanks FUNADESP/Unigranrio for a personal grant that helped her in her endocarditis research.