Despite potent antiretroviral therapy, HIV still causes brain damage. Better penetration into the CNS and efficient elimination of monocyte/macrophages reservoirs are two main characteristics of an antiretroviral drug that could prevent brain damage. The aim of our study was to assess efficacy of three antiretroviral drug scores to predict brain atrophy in HIV-infected patients.

MethodsA cross sectional study consisting of 56 HIV-infected patients with controlled viremia, who had no clinically evident neurocognitive impairment. All patients had MRI of the head. A typical T2 transversal slice was analyzed and ventricles–brain ratio (VBr) as an overall brain atrophy index was calculated. Three antiretroviral drug scores were used and correlated with VBr: 2008 and 2010 CNS penetration effectiveness scores (ΣCPE2008 and ΣCPE2010) and the recently established monocyte efficacy (ΣME) score. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsΣCPE2010 was significantly associated with VBr in both univariate (r=−0.285, p=0.033) and multivariate (β=−0.299, p=0.016) regression models, while ΣCPE2008 was not (r=−0.141, p=0.300 and β=−0.156, p=0.214). ΣME was associated with VBr in multivariate model only (r=−0.297, p=0.111 and β=−0.406, p=0.029). Age and reported duration of HIV infection were also significant predictors of overall brain atrophy in multivariate regression models.

ConclusionsAlthough based on similar type of research, ΣCPE2010 is a superior drug score compared to ΣCPE2008. ΣME is an efficient drug score in determining brain damage. Both ΣCPE2010 and ΣME scores should be taken into account in preventive strategies of brain atrophy and neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected patients.

Different neuropathological and neuroradiological studies have shown that HIV-infected patients have significant reduction of the brain parenchyma of both cortical1,2 and subcortical brain regions.3,4 Despite effective HIV treatment, brain tissue remains susceptible to the virus1 as there is still detectable viral load in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF),5 brain volume loss6–8 and neurocognitive (NC) impairment.9,10 As shown in euroSIDA study, antiretroviral therapy significantly reduced the incidence of NC disorders caused by HIV,11 but its prevalence is still high (15–40%).12 Due to the blood–brain and the blood–CSF barriers, drug entry into the CNS is limited, which results in incomplete viral suppression in the CNS. That might be the reason why CNS acts as a reservoir for viral persistence and evolution of drug resistance, in which the virus acquire unique properties.13,14 Different penetration levels of antiretroviral drugs into the CNS have been quantified by CNS-penetration effectiveness score (CPE), established by Letendre et al.15 The score has 2008 (CPE2008) and 2010 (CPE2010) versions.15,16 Higher CPE means not only a better penetration efficacy into the CNS, but also a decline of new CNS events and even a decline in mortality rates.17 In contrast, a study by McManus et al.18 has not reached the same conclusion.

As viral reservoirs, circulating monocytes are considered to be responsible for chronic HIV infection in the brain. Activated monocytes traffic to the brain, where they become macrophages and produce inflammatory molecules. Increased inflammatory milieu results in damage of the brain tissue and eventually leads to NC impairment.19–23 Autopsy studies have shown increased number of macrophages in brain despite antiretroviral treatment.24 Therefore, antiretroviral drugs that are effective in destroying viral reservoirs (monocytes and brain macrophages) should slow down brain atrophy and NC deterioration caused by HIV. Collecting in vitro data about effectiveness of antiretroviral drugs against activated monocytes/macrophages, Shikuma et al. established monocyte efficacy (ME) score of drugs and proved its efficacy in predicting NC impairment.25

To our knowledge, there is only one study in which these three drugs scores were compared and NC parameters were used as outcome.25 There is no neuroimaging study in which ME score was validated and compared with CPE scores in assessing brain atrophy in HIV-infected patients.

The aim of our study was to compare recently established ME score with two CPE scores in terms of efficacy in predicting brain atrophy in HIV-infected patients. We also wanted to investigate other potential determinants of brain atrophy, such as age, nadir and current CD4+ T-cell count and durations of HIV infection and HAART.

Materials and methodsStudy design and subjectsThis cross-sectional study consisted of HIV-infected patients receiving care at the HIV/AIDS Center, Infectious Diseases Clinic, Clinical Center of Vojvodina in Novi Sad, Serbia. There were 81 patients, who had undergone MRI of the brain, which is around one-third of all registered patients. All MRIs were performed at the Diagnostic Imaging Center, Oncology Institute in Sremska Kamenica, Serbia from July 2011 to July 2014. Out of the 81 patients, 63 were on HAART and had plasma HIV RNA<50copies/mL for at least three months. Exclusion criteria were presence of focal brain changes on MRI, clinically evident NC impairment, co-infection with hepatitis C virus, and intravenous drug use. In a total of 56 patients who met all the above criteria (Suppl. 1) the International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) was applied as a neuropsychological screening test, established by Sacktor et al.26 in which 0 is the worst and 12 is the best score. The study is a part of a larger project, which has been approved by the local ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

MorphometryFor every included patient typical T2 transversal MRI slices were obtained in which lateral ventricles are most visible. Ventricular–brain ratio (VBr) was calculated by measuring lateral ventricles area and dividing by the brain area at the same level. This is a marker of overall brain atrophy and has already been used in studies on brain atrophy related to diseases including HIV.27,28

Antiretroviral drugs and drug scoring systemsAll patients were on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) that consisted of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) plus a protease inhibitor (PI) and/or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). Three antiretroviral drug-scoring systems were used: 2008 and 2010 (CPE2008 and CPE2010) CPE score versions,15,16 and ME score.25 All scores for antiretroviral regimens were calculated as a sum of the individual grades from the score. There are no published data on ME score of lopinavir/ritonavir (lpv/r) and darunavir. Therefore, for 26 (46.4%) patients, who were on lpv/r or darunavir, it was not possible to calculate ΣME values.

Statistical analysesData were evaluated and statistically processed using the software package IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21. T-test for independent samples was used to assess differences in means of brain atrophy index between two groups. Pearson's coefficient was used for estimating correlation between brain atrophy index and parameters, such as age, nadir and current CD4+ T-cell count, duration of HIV, duration of HAART, and drug scores. Multivariate linear regression analyses were performed for assessing predictors of brain damage. All tests were two-tailed. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsMean age of patients in the study was 41 years, 89% were males. Demographic and virologic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients. Data are shown as mean value (SD) or percentage.

| Total (n=56) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 41.1 (9.6) |

| Male gender | 89% |

| Virology and therapy | |

| Nadir CD4+ T-cell count, cells/mm3 | 186.0 (112.5) |

| Current CD4+ T-cell count, cells/mm3 | 472.5 (254.1) |

| HIV-positive status, months | 69.9 (52.6) |

| Duration of therapy, months | 39.4 (35.4) |

| Neuropsychological screening | |

| IHDS, points | 10.9 (1.0) |

| Brain morphometry | |

| VBr, ×1000 | 84.2 (16.2) |

IHDS, International HIV Dementia Scale; VBr, ventricles–brain ratio.

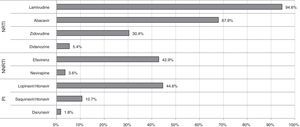

Lamivudine was taken by 94.6%, abacavir by 67.9%, lpv/r by 44.6%, efavirenz by 42.9%, zidovudine by 30.4%, saquinavir/ritonavir by 10.7%, didanosine by 5.4%, nevirapine by 3.6%, and darunavir by 1.8% of patients (Fig. 1). Based on the presence of efavirenz in the regimen the patients were categorized into two groups. There were no significant differences in VBr (p=0.926) and IHDS (p=0.501) values between these two groups.

Mean values, SD, medians, IQR, minimal and maximal values of ΣCPE2008, ΣCPE2010, and ΣME scores are shown in Table 2. ΣME significantly correlated with ΣCPE2010 (r=0.546, p=0.002), while the association between ΣME and ΣCPE2008 was not significant (r=0.097, p=0.609). Correlation between two the CPE versions (ΣCPE2008 and ΣCPE2010) was highly significant (r=0.644, p<0.001).

Mean, median and measures of dispersion for three drug scores of patients in the study.

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΣCPE2008 | 2.16 | 0.45 | 2 | 2.0–2.5 | 1–3 |

| ΣCPE2010 | 8.18 | 0.81 | 8 | 8–9 | 6–10 |

| ΣME | 152.80 | 35.52 | 153 | 153–170 | 73–200 |

ΣCPE2010, CNS-penetration effectiveness score (version 2010) of the HAART regimen.

ΣCPE2008, CNS-penetration effectiveness score (version 2008) of the HAART regimen.

ΣME, monocyte efficacy score of the HAART regimen.

A linear regression model was built including each of the three drug scoring systems. The independent variables age, nadir and current CD4+ T-cell count, duration of HIV status and HAART therapy were included in each of the three regression models. The dependent variable in all models was VBr, a measure of brain atrophy. Results of these linear regression models are presented in Table 3. In univariate analyses age (r=0.283, p=0.035) and ΣCPE2010 (r=−0.285, p=0.033) were found to be significantly associated with brain atrophy. However, in multivariate analyses, both ΣCPE2010 and ΣME were significant predictors of brain atrophy (β=−0.299, p=0.016 and β=−0.406, p=0.029, respectively). ΣCPE2008 was neither significantly associated in univariate (r=−0.141, p=0.300) nor in multivariate (β=−0.156, p=0.214) regression models. Age and duration of HIV-positive status were parameters that were significantly associated with brain atrophy in all three multivariate models (Table 3).

Linear regression models of three drug scoring systems with brain atrophy index (VBr) as a dependant variable.

| Regression model | Independent variables | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient r | p | Regression coefficient β | p | Model significance | ||

| ΣCPE2010 | Age | 0.283 | 0.035 | 0.390 | 0.003 | p=0.001 |

| Nadir CD4+ count | −0.113 | 0.406 | ||||

| Current CD4+ count | −0.112 | 0.413 | ||||

| Duration of HIV | 0.235 | 0.082 | 0.291 | 0.022 | ||

| Duration of HAART | 0.238 | 0.078 | ||||

| ΣCPE2010 | −0.285 | 0.033 | −0.299 | 0.016 | ||

| ΣCPE2008 | Age | 0.283 | 0.035 | 0.365 | 0.006 | p=0.008 |

| Nadir CD4+ count | −0.113 | 0.406 | ||||

| Current CD4+ count | −0.112 | 0.413 | ||||

| Duration of HIV | 0.235 | 0.082 | 0.322 | 0.015 | ||

| Duration of HAART | 0.238 | 0.078 | ||||

| ΣCPE2008 | −0.141 | 0.300 | −0.156 | 0.214 | ||

| ΣME | Age | 0.283 | 0.035 | 0.348 | 0.045 | p=0.022 |

| Nadir CD4+ count | −0.113 | 0.406 | ||||

| Current CD4+ count | −0.112 | 0.413 | ||||

| Duration of HIV | 0.235 | 0.082 | 0.377 | 0.043 | ||

| Duration of HAART | 0.238 | 0.078 | ||||

| ΣME | −0.297 | 0.111 | −0.406 | 0.029 | ||

ΣCPE2010, CNS-penetration effectiveness score (version 2010) of the HAART regimen.

ΣCPE2008, CNS-penetration effectiveness score (version 2008) of the HAART regimen.

ΣME, monocyte efficacy score of the HAART regimen.

Numerous studies emphasized basal ganglia as the main region in which pathological effects of HIV take place in the CNS.4,6 Other studies showed that numerous cortical parts of the brain are damaged as well.29,30 Therefore, we have used VBr in our study, as an index of overall brain atrophy.

Our hypothesis was that the level of an antiretroviral drug in the CNS affects all steps in the neuropathogenesis chain. The first step includes inflammatory changes and neurological injury. It can be diagnosed with CSF markers and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Atrophic changes occur in the second step, which can be evaluated with different neuroimaging methods. Structural damage further results in functional changes, the hallmark of the third step. These functional changes are observed as NC impairment and can be diagnosed using different neuropsychological tests. This integral approach has been proved with correlations between structural and functional variables in numerous studies,3,31–35 although there are also studies in which correlations were not shown.2,6

One of the aims of our study was to compare two CPE scoring systems. The original ΣCPE2008 scoring system was based on clinical, pharmacological and chemical reports on antiretroviral drugs. In literature it was mostly indicated as a predictor of decreasing viral load in CSF15,36; in neuropsychological studies the results are controversial.37–40 Imaging studies failed to prove ΣCPE2008 as a predictor of brain atrophy.4,7,8 Our results are in line with published reports as we found no significant association between ΣCPE2008 and VBr.

Although such an outcome was expected due to similar results previously reported, we hypothesized that ΣCPE2008 could be used to predict brain atrophy as it strongly correlates with ΣCPE2010. There are some possible reasons why the association is not shown:

- –

Sum of score values range is too narrow to show small differences.

- –

CPE scale classifies drugs into only three categories, masking the differences among drugs in the same category.

On the contrary, a revised ΣCPE2010 was shown to be a good predictor of brain atrophy in both univariate and multivariate regression models. According to our results, it is expected that HAART regimens consisting of drugs with higher CPE2010 score have a protective effect on the brain tissue. The study by Ciccarelli et al., using NC performance as the outcome of interest, found results regarding ΣCPE2008 and ΣCPE2010 similar to our study. In their study ΣCPE2010 was emphasized as an improved predicting tool and a step forward compared to ΣCPE2008.41

There are very few neuroimaging studies that have examined ΣCPE2010. Ragin et al. conducted a neuroimaging study that showed association between brain atrophy and ΣCPE2010.29 On the contrary, there are numerous studies in which NC performance was used as an outcome. Some studies have shown significant positive association, whereas others have not shown any association; furthermore, other studies have found even worse NC performance in patients who were on higher CPE drug regimens.31,41–43 Possible reasons for such discrepancy might be heterogonous cohorts regarding virological status and NC performance, HCV co-infection, and intravenous drug use among examined patients. Therefore, our cohort consisted only of neuroasymptomatic patients with HIV RNA<50copies/mL for at least three months. In order to reduce possible biases,44,45 we excluded HCV-HIV co-infected patients and intravenous drug users. Thus, a relatively homogenous sample was gathered representing the majority of our HIV-infected patients. Further longitudinal studies are needed to provide more data about exact influences of different variables on brain damage in these patients.

Possible neurotoxic effects of drugs with better penetration mentioned in several studies38,39,43 were not identified in our study. Efavirenz is the most often emphasized drug for its potential neurotoxicity.46 However, in our study the relationship between the use of efavirenz and brain damage was not found.

Reported duration of HIV infection was significantly associated with brain atrophy. Results suggest that chronic infection of the CNS permanently damages brain tissue and causes brain atrophy, which has been documented in the literature.4,30,34 Hidden behind blood–brain barrier, relatively isolated environment increases the magnitude of damage. This finding suggests that patients should be always asked to provide, if possible, approximate date of infection with HIV, as this information might be important to estimate the extent of brain atrophy. The obvious problem of this parameter is its subjective nature. Often it is not possible to establish the approximate time of infection due to large number of partners and rarity of testing. As life expectancy of HIV-infected patients continuously increases, duration of HIV positive status also increases. According to our results, higher ΣCPE2010 might decrease effects of HIV duration in terms of brain atrophy.

Surprisingly, other HIV-related parameters, nadir and current CD4+ T-cell count, were not associated with VBr in our study. As for nadir CD4+ T-cell count, results suggest that brain atrophy is affected more by the duration of immune compromise than its “depth”. A failure to prove significant association between brain atrophy and current CD4+ T-cell count could be explained by individualized pattern of the immunological recovery in patients with undetectable viral load. Therefore its effect on the CNS is unpredictable. In literature, results in regard to effects of nadir and current CD4+ T-cell count on brain damage extent/NC impairment are controversial.1,6,29,47

Duration of HAART was significantly associated with VBr in univariate analyses, similar to duration of HIV. Duration of HAART and duration of HIV are highly correlated with each other. For this reason it was necessary to select one of these two variables for multivariate analyses. As duration of HAART depends on the duration of HIV, we have included duration of HIV in multivariate analyses. A similar reasoning was used in the study by Kuper et al.8

As it was already mentioned, this is the first neuroimaging study, to our knowledge, in which association between a neuroimaging parameter and ME score is investigated. ME score is based on the hypothesis that suppression of HIV in the CNS actually means elimination of monocyte/macrophage reservoirs. Our results showed that ΣME is negatively associated with brain damage, suggesting that drugs that are effective in eliminating monocyte/macrophage reservoirs might protect brain tissue from injury. Similar results were shown in the study by Shikuma et al., in which ME score was associated with NC performance.25

Effective ΣME drug regimens provide a completely new insight in prevention and treatment of the neurocognitive disorders caused by HIV. Elimination of reservoirs can start even before activated monocytes cross the blood–brain barrier and continues as brain macrophages enter into the CNS. In that sense, theoretically the ideal antiretroviral drug would be one that effectively destroys monocyte/macrophage reservoirs (in the periphery and in the CNS) and penetrates well into the CNS. So, combining both CPE and ME drug scores and integrating both qualities of a drug would be a step forward to a better understanding of pathological effects of HIV in the CNS and effects of HAART onto counteracting them. For establishing such a scoring system, larger cohorts and further investigation on pharmacokinetics and pharmacology of the drugs are needed.

In that sense, HAART regimens with high ΣME values could be more effective in clearing latent reservoirs not only in the CNS, but also throughout the whole body, as systemic clearing viral reservoirs would lead to eradication of the HIV.48 To prove this, longitudinal studies are needed.

The main limitation of ΣME score is lack of known ME values for darunavir, atazanavir, and most importantly for lpv/r, although it is well known that this drug accumulates in monocytes.49 Further in vitro analyses are needed to determine acute infection EC50 values of these drugs and calculate their ME values.

ConclusionsAlthough the sample size might seem small and a follow-up would be a logical next step, the expensive and sophisticated imaging methods used in this study are not done routinely. Previous similar neuroimaging studies were done on a similar or even smaller sample. Although the marker used in this study was used in other studies on brain atrophy, there are now more accurate techniques to define brain volumes. Despite these limitations, our results suggest a few important conclusions. Firstly, ΣCPE2010 is a superior drug-scoring system compared to ΣCPE2008. Secondly, ΣME is an effective drug-scoring system in determining brain damage. Thirdly, both ΣCPE2010 and ΣME scores should be taken into account in preventing strategies of brain atrophy and NC impairment in HIV-infected patients.

Controversial results in literature concerning drug-scoring systems underscore the need for a new scoring system. One of the possibilities is to build a mathematical model combining ΣCPE2010 and ΣME scores, in which both important qualities of a drug (penetration in the CNS and elimination of reservoirs) would be presented. This would require larger longitudinal studies. The use of ME scoring system is limited due to missing values for some common HIV drugs, such as darunavir, atazanavir, and lpv/r.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank all the patients for their involvement in the study. We also thank the nursing staff at the HIV/AIDS Center of Infectious Diseases Clinic in Novi Sad and at the Diagnostic Imaging Center of Oncology Institute in Sremska Kamenica.

This study was supported by the Provincial Secretariat for Science and Technological Development, Government of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, Serbia (project 114-451-2255/2011-01).