Two types of Epstein Barr virus (EBV1/EBV2) have been shown to infect humans. Although their genomes are similar, the regions containing the EBNA genes differ. This study aimed to characterize the EBV genotypes of infectious mononucleosis (IM) cases in the metropolitan region of Belém, Brazil, from 2005 to 2016. A total of 8295 suspected cases with symptoms/signs of IM were investigated by infectious disease physicians at Evandro Chagas Institute, Health Care Service, from January 2005 to December 2016. Out of the total, 1645 (19.8%) samples had positive results for EBV by enzyme immunoassay and 251 (15.3%) were submitted to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, using the EBNA3C region, in order to determine the type of EBV. Biochemical testing involving aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase were also performed. EBV type was identified by PCR in 30.3% (76/251) of individuals; of those, 71.1% (54/76) were classified as EBV1, 17.1% (13/76) as EBV2, and 11.8% (9/76) as EBV1 + EBV2. The main symptoms/signs observed with EBV1 infection were cervical lymphadenopathy (64.8%, 35/54), fever (63%, 34/54), headache (20.4%, 11/54), arthralgia (20.4%, 11/54), and exanthema (18.5%, 10/54). EBV2 infection was detected in all but two age groups, with an average age of 24 years. The most common signs/symptoms of EBV2 were fever (76.9%, 10/13), average duration of 18 days, and lymphadenopathy (69.2%, 9/13). In contrast, EBV1 + EBV2 coinfections were more frequent in those aged five years or less (20.0%, 2/10). The symptoms of EBV1 + EBV2 coinfection included fever (66.7%, 6/9), and cervical lymphadenopathy and headache (33.3%, 3/9) each. The mean values of hepatic enzymes according to type of EBV was significantly different (p < 0.05) in those EBV1 infected over 14 years of age. Thus, this pioneering study, using molecular methods, identified the EBV genotypes in 30.3% of the samples, with circulation of EBV1, EBV2, and EBV1 + EBV2 co-infection in cases of infectious mononucleosis in the northern region of Brazil.

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) belongs to the order Herpesvirales, family Herpesviridae, subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae, genus Lymphocryptovirus and species Human gammaherpesvirus 4.1 EBV was the first oncogenic virus shown to infect humans.2,3 The hexagonal nucleocapsid viral particles are formed with linear, double-stranded, enveloped DNA, with a diameter ranging from 180 to 200 nm.4

Although symptomatic infections with these viruses can occur benignly, EBV has been implicated in the genesis of a variety of lymphoproliferative disorders and severe epithelial neoplasms, such as African Burkitt’s lymphoma5 and nasopharyngeal carcinoma6.

In Brazil, several studies have documented high levels of antibodies to EBV in the studied populations. Investigation conducted by Monteiro et al.7 found that at least 70% of serum samples analyzed in the city of Belém, state of Pará, contained IgG antibodies to EBV, with rates in outpatient clinics ranging from 53.8% to 95.6% and at communities from 81.1% to 100%. Positivity rates were high even in younger age groups with 10.6% (25/234) of children and adolescents in northern Brazil showing active and recent infection (infectious mononucleosis).8

Data from Young and Murray9 demonstrated that EBV is present in approximately 90% of individuals and is controlled by the immune system, mainly by cellular immunity, which may make the person more susceptible to virus proliferation and may trigger lymphoproliferative disorders.10

The phenotypic difference between EBV1 and EBV2 is more evident during immortalization of B cells in lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) by EBV1 compared to EBV2. This fact reinforces the biological and functional difference between the two viral types, where B cell immortalization in vitro was shown to be more effective by EBV1.11 According to Mandell et al.12 the differentiation of genotypes can clarify the different immune responses during viral persistence.

Epidemiological studies on EBV1 and EBV2 types characterizing clinical, demographic (sex, age and origin) and molecular findings in the metropolitan region of Belém, are still lacking. Due to their characteristics in terms of viral persistence, EBVs may induce chronic infections and reactivations in human populations with genetic competence, possibly leading to oncogenic outcomes.

The aim of this study was to determine the types of EBV (EBV1/EBV2) in clinical cases of IM in the metropolitan area of Belém between 2005 and 2016.

Material and methodsPatientsThis was a retrospective study involving serum samples collected from January 2005 to December 2016, from 8295 clinically suspected individuals of having IM. Patients were screened by infectious diseases physicians from the Evandro Chagas Institute, Ministry of Health of Brazil (IEC/MS), Reference Center for the Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases in Northern Brazil to identify those with serological confirmation.

Laboratory analysisSerum samples were collected and tested for EBV using an enzyme immune assay as well as for biochemical analyses. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by Ficoll-Hipaque density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep Nycomed Pharma AS, Norway) for use in future polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests.

Immunoenzymatic assay (EIA)EBV screening in samples was carried out using the RIDASCREEN® enzyme immunoassay kit (R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany), which detects IgG and IgM antibodies to viral capsid antigen (VCA), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Nucleic acid extractionPBMC DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Identification of the EBV EBNA3C geneThe primer EBNA-3C was used to identify both types of EBV,13 because the primary flanking region can differentiate them based on the resulting product: EBV1 with 153 base pairs (bp) and EBV2 with 246 bp.

Five microliters of the eluted DNA was used for PCR amplification with a primer concentration of 0.05 μM (EBNA3C1, forward: 5′-GCCAGAGGTAAGTGGACTTT-3′ and EBNA3C2, reverse: 5′-TGGAGAGGTCAGGTTACTTA-3′). PCR was performed in 0.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes in a final volume of 25 μL of mixture containing 0.125 μL (5 U/μL) of Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen™, Brazil), 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen™, Brazil), 0.2 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen™, Brazil), 5 μL of 10X buffer (Invitrogen™, Brazil) and 2 μL (20 μM/μL) of each the above mentioned primers.

The PCR cycle conditions (PTC 100/Peltier Effect Cycle, Thermostable Controller) were as follows: denaturation of the DNA at 94 °C for 1 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. For all PCR analyses, water was used as negative control, and B958 and P3HR1 cell lines were used as positive controls for EBV1 and EBV2, respectively. The amplified products were subjected to 2% agarose gel electrophoresis using ethidium bromide and visualized by UV illumination.

Biochemical dosages analysesBiochemical tests such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST; reference: 4–40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT; reference: 2–41 U/L), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT; reference: 5–55 U/L) were performed on an automated clinical biochemistry analyzer (COBAS INTEGRA clinical PLUS 400/ROCHE).

Statistical analysisResults were organized and stored in a database in Microsoft Office Access 2016, Statistical Package for Social Science — SPSS 17.0. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.14

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the research ethics committees of the Evandro Chagas Institute (CAAE number 65332717.2.0000.0019, with legal opinion number 2098453, of June 4, 2017).

ResultsSerological analysisOut of 8295 serum samples collected and tested for EBV by EIA, 19.8% (1645/8295) were positive for IgM antibodies. Of these samples, a subgroup of 251 (15.3%) was used in this research and tested for the detection of EBV by PCR. IgG antibody screening was also carried out in 162 (64.5%) of these positive samples and all of them had negative results.

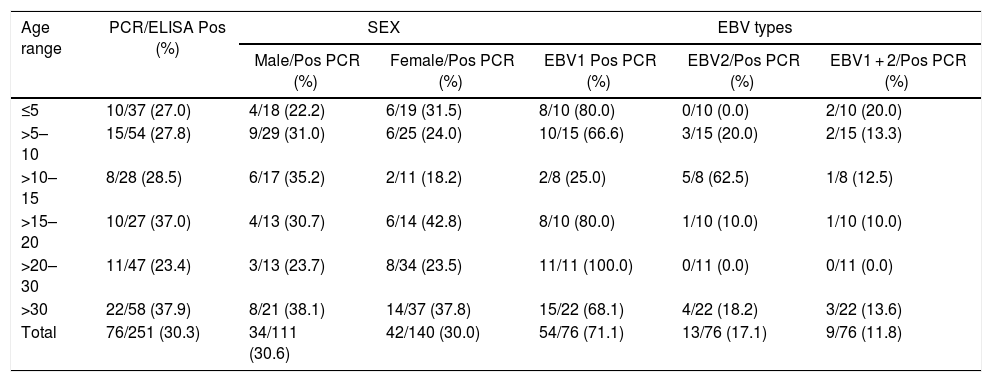

Molecular detectionThe type of EBV was identified by PCR in 30.3% (76/251) of the IgM positive samples with the EBNA-3C primer. The age groups 15–20 years and >30 years had slightly higher positivity by PCR (37.0%, p = 0.557) (Table 1). PCR positivity rates were similar among males (30.6%, 34/111) and females (30.0%, 42/140). Moreover, the majority of PCR positive cases were male aged >30 (38.1%) years; however, among females the positivity rate was higher in the age group 15–20 (42.8%) years.

Detection of the EBNA3C gene by PCR in 251 patients with infectious mononucleosis and anti-IgM positive for EBV, according to age, sex and type. Samples collected from 2005 to 2016.

| Age range | PCR/ELISA Pos (%) | SEX | EBV types | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Pos PCR (%) | Female/Pos PCR (%) | EBV1 Pos PCR (%) | EBV2/Pos PCR (%) | EBV1 + 2/Pos PCR (%) | ||

| ≤5 | 10/37 (27.0) | 4/18 (22.2) | 6/19 (31.5) | 8/10 (80.0) | 0/10 (0.0) | 2/10 (20.0) |

| >5–10 | 15/54 (27.8) | 9/29 (31.0) | 6/25 (24.0) | 10/15 (66.6) | 3/15 (20.0) | 2/15 (13.3) |

| >10–15 | 8/28 (28.5) | 6/17 (35.2) | 2/11 (18.2) | 2/8 (25.0) | 5/8 (62.5) | 1/8 (12.5) |

| >15–20 | 10/27 (37.0) | 4/13 (30.7) | 6/14 (42.8) | 8/10 (80.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | 1/10 (10.0) |

| >20–30 | 11/47 (23.4) | 3/13 (23.7) | 8/34 (23.5) | 11/11 (100.0) | 0/11 (0.0) | 0/11 (0.0) |

| >30 | 22/58 (37.9) | 8/21 (38.1) | 14/37 (37.8) | 15/22 (68.1) | 4/22 (18.2) | 3/22 (13.6) |

| Total | 76/251 (30.3) | 34/111 (30.6) | 42/140 (30.0) | 54/76 (71.1) | 13/76 (17.1) | 9/76 (11.8) |

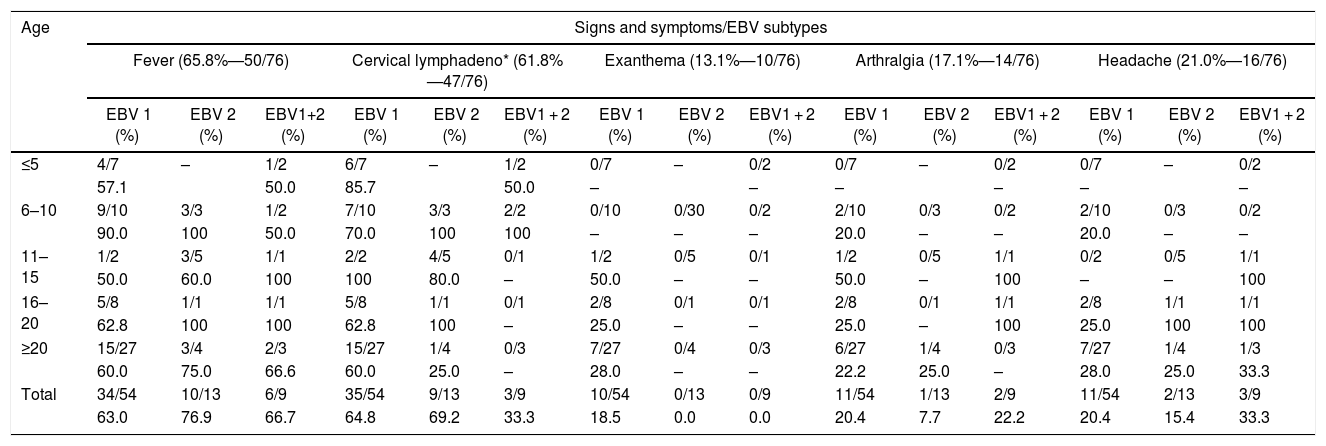

Classification of the positive samples by EBV type showed that 71.1% (54/76) were EBV1, 17.1% (13/76) EBV2, and 11.8% (9/76) EBV1 + EBV2 coinfection; 76.3% (58/76) PCR positive patients came from the cities of Belém, 22.4% (17/76) from Ananindeua, and 1.3% (1/76) from Marituba. Multiple signs and symptoms were observed in these cases (Table 2), including fever in 65.8% (50/76), cervical lymphadenomegaly in 61.8% (47/76), exanthema in 13.1% (10/76), arthralgia in 17.1% (14/76), and headache in 21.0% (16/76).

Main symptoms observed in 76 EBV-infected cases, by age and type, who provided samples collected from 2005 to 2016.

| Age | Signs and symptoms/EBV subtypes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever (65.8%—50/76) | Cervical lymphadeno* (61.8%—47/76) | Exanthema (13.1%—10/76) | Arthralgia (17.1%—14/76) | Headache (21.0%—16/76) | |||||||||||

| EBV 1 (%) | EBV 2 (%) | EBV1+2 (%) | EBV 1 (%) | EBV 2 (%) | EBV1 + 2 (%) | EBV 1 (%) | EBV 2 (%) | EBV1 + 2 (%) | EBV 1 (%) | EBV 2 (%) | EBV1 + 2 (%) | EBV 1 (%) | EBV 2 (%) | EBV1 + 2 (%) | |

| ≤5 | 4/7 | – | 1/2 | 6/7 | – | 1/2 | 0/7 | – | 0/2 | 0/7 | – | 0/2 | 0/7 | – | 0/2 |

| 57.1 | 50.0 | 85.7 | 50.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| 6–10 | 9/10 | 3/3 | 1/2 | 7/10 | 3/3 | 2/2 | 0/10 | 0/30 | 0/2 | 2/10 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 2/10 | 0/3 | 0/2 |

| 90.0 | 100 | 50.0 | 70.0 | 100 | 100 | – | – | – | 20.0 | – | – | 20.0 | – | – | |

| 11–15 | 1/2 | 3/5 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 4/5 | 0/1 | 1/2 | 0/5 | 0/1 | 1/2 | 0/5 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 1/1 |

| 50.0 | 60.0 | 100 | 100 | 80.0 | – | 50.0 | – | – | 50.0 | – | 100 | – | – | 100 | |

| 16–20 | 5/8 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 5/8 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/8 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/8 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 2/8 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 62.8 | 100 | 100 | 62.8 | 100 | – | 25.0 | – | – | 25.0 | – | 100 | 25.0 | 100 | 100 | |

| ≥20 | 15/27 | 3/4 | 2/3 | 15/27 | 1/4 | 0/3 | 7/27 | 0/4 | 0/3 | 6/27 | 1/4 | 0/3 | 7/27 | 1/4 | 1/3 |

| 60.0 | 75.0 | 66.6 | 60.0 | 25.0 | – | 28.0 | – | – | 22.2 | 25.0 | – | 28.0 | 25.0 | 33.3 | |

| Total | 34/54 | 10/13 | 6/9 | 35/54 | 9/13 | 3/9 | 10/54 | 0/13 | 0/9 | 11/54 | 1/13 | 2/9 | 11/54 | 2/13 | 3/9 |

| 63.0 | 76.9 | 66.7 | 64.8 | 69.2 | 33.3 | 18.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.4 | 7.7 | 22.2 | 20.4 | 15.4 | 33.3 | |

Regarding the number of days with fever, 22% (11/50) reported fever for up to five days, 16% (8/50) for 10 days, 20% (10/50) for 15 days, 16% (8/50) for 20 days, and 16% (8/50) for more than 20 days, while 10% (5/50) had no such information in their record.

EBV1 was detected in all age groups. On the other hand, EBV2 was verified at a lower rate or absent, except in the age group 10–15 years, when it presented a much higher rate (62.5%) than EBV1 (25.0%). With the exception of the group 20–30 years, all other age groups had at least one case of coinfection (Table 1). EBV1 accounted for 79.1% (34/43) of individuals over 15 years old, with an average age of 22.6 years; 61.1% (33/54) of women were infected by EBV1, whereas 38.9% (21/54) were detected in men. Additionally, 75.9% (41/54) EBV1 infected individuals came from Belém, 22.2% (12/54) from Ananindeua, and 1.9% (1/54) Marituba.

Regarding clinical symptoms or signs observed in patients infected with EBV1, the prevailing symptoms were cervical lymphadenopathy in 64.8% (35/54), fever in 63.0% (34/54), headache and arthralgia in 20.4% (11/54), and exanthema in 18.5% (10/54) (Table 2)

EBV2 infection was also detected in all but two age groups groups, with a mean age of 24 years. This EBV type was more frequent among males (76.9%, 10/13) than females (23.1%, 3/13) (Table 1).

EBV1 + EBV2 co-infected patients presented with fever, cervical lymphadenopathy and headache as the most frequent symptoms (66.7%; 6/9) and 33.3% (3/9), respectively (Table 2). Coinfection was more common in individuals aged five years or less (20.0%; 2/10) (Table 1). The mean age of EBV1 + EBV2 coinfected patients was 21 years. There more cases among women (66.7%; 6/9) than among men (33.3%; 3/9).

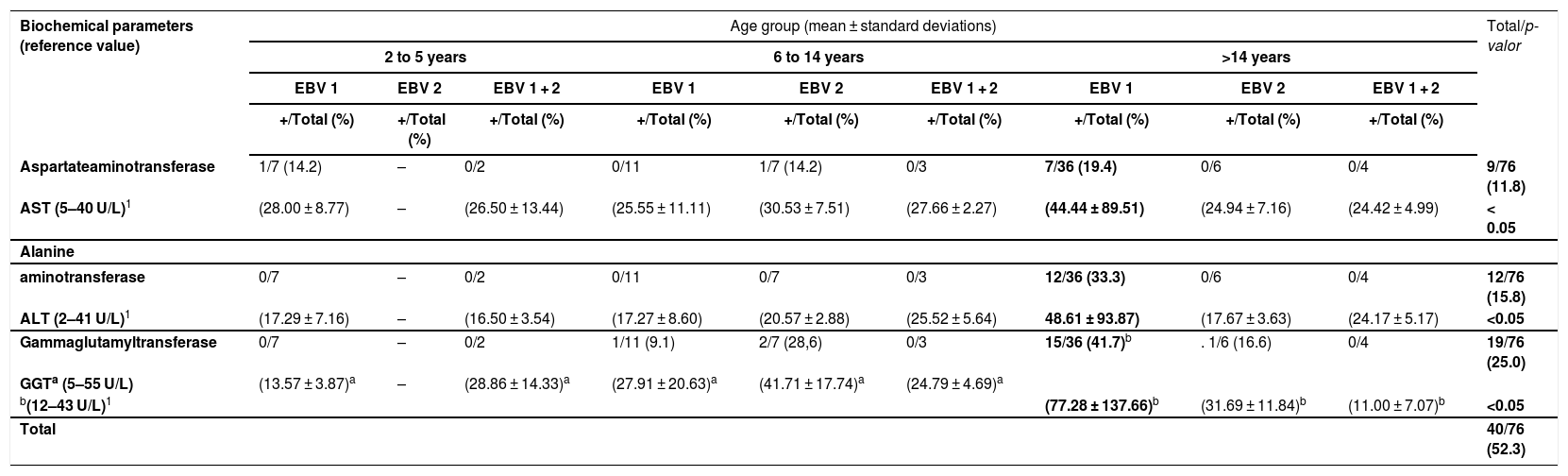

Regarding hepatic function tests, overall 14.8% (8/54) of EBV1-infected cases had elevated AST levels (normal range 5−40 U/L), while the age group of >14 years abnormal values in 19.4% (7/36) of the cases. For EBV2 infection, 7.7% (1/13) had elevated AST compared to 14.2%, (1/7) in the age group six to 14 years (Table 3).

Hepatic enzymes (AST, ALT and GGT) elevations according to age and EBV types, in 76 PCR positive samples using the EBNA3C gene, collected from 2005 to 2016.

| Biochemical parameters (reference value) | Age group (mean ± standard deviations) | Total/p-valor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to 5 years | 6 to 14 years | >14 years | ||||||||

| EBV 1 | EBV 2 | EBV 1 + 2 | EBV 1 | EBV 2 | EBV 1 + 2 | EBV 1 | EBV 2 | EBV 1 + 2 | ||

| +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | +/Total (%) | ||

| Aspartateaminotransferase | 1/7 (14.2) | – | 0/2 | 0/11 | 1/7 (14.2) | 0/3 | 7/36 (19.4) | 0/6 | 0/4 | 9/76 (11.8) |

| AST (5–40 U/L)1 | (28.00 ± 8.77) | – | (26.50 ± 13.44) | (25.55 ± 11.11) | (30.53 ± 7.51) | (27.66 ± 2.27) | (44.44 ± 89.51) | (24.94 ± 7.16) | (24.42 ± 4.99) | < 0.05 |

| Alanine | ||||||||||

| aminotransferase | 0/7 | – | 0/2 | 0/11 | 0/7 | 0/3 | 12/36 (33.3) | 0/6 | 0/4 | 12/76 (15.8) |

| ALT (2–41 U/L)1 | (17.29 ± 7.16) | – | (16.50 ± 3.54) | (17.27 ± 8.60) | (20.57 ± 2.88) | (25.52 ± 5.64) | 48.61 ± 93.87) | (17.67 ± 3.63) | (24.17 ± 5.17) | <0.05 |

| Gammaglutamyltransferase | 0/7 | – | 0/2 | 1/11 (9.1) | 2/7 (28,6) | 0/3 | 15/36 (41.7)b | . 1/6 (16.6) | 0/4 | 19/76 (25.0) |

| GGTa (5–55 U/L) | (13.57 ± 3.87)a | – | (28.86 ± 14.33)a | (27.91 ± 20.63)a | (41.71 ± 17.74)a | (24.79 ± 4.69)a | ||||

| b(12–43 U/L)1 | (77.28 ± 137.66)b | (31.69 ± 11.84)b | (11.00 ± 7.07)b | <0.05 | ||||||

| Total | 40/76 (52.3) | |||||||||

Concerning ALT, values above the reference range (2–41 U/L) were significantly more common among EBV1-infected cases aged 14 years and above (33.3%; 12/36) than in age goups 2–5 and 6–14 years (Table 3).

GGT was within the normal range (5–55 U/L) in the age group 2–5 years. GGT was elevated in 9.1% (1/11) and 28.6% (2/7) in EBV1- and EBV2-infected cases, respectively, in the age group 6–14 years. In those over 14 years of age, GGT was above the upper limit of normality for that age-range (12–43 U/L) in 41.7% (15/36) and 16.6% (1/6), respectively, of EBV1- and EBV2-infected cases (Table 3).

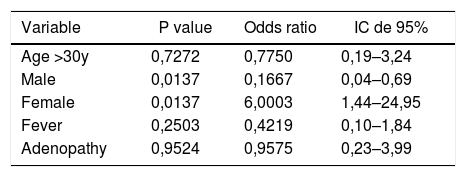

Multiple logistic regression (MLR) showed that among 76 positive cases for the EBNA3C gene, female sex was six-fold more likely to be infected with EBV subtype 1 (p = 0.0137; OR = 6.003), after adjusting for age and clinical data (fever and adenopathy) (Table 4).

Main variables analyzed of EBV type 1 infected cases who provided the samples collected from 2005 to 2016.

| Variable | P value | Odds ratio | IC de 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >30y | 0,7272 | 0,7750 | 0,19–3,24 |

| Male | 0,0137 | 0,1667 | 0,04–0,69 |

| Female | 0,0137 | 6,0003 | 1,44–24,95 |

| Fever | 0,2503 | 0,4219 | 0,10–1,84 |

| Adenopathy | 0,9524 | 0,9575 | 0,23–3,99 |

Primary EBV infection is usually asymptomatic and may progress to a benign lymphoproliferative disease known as IM, especially in late childhood or early adulthood of developing countries.4

Infectious mononucleosis is characterized by significant clinical polymorphisms in which factors such as age, immune status and comorbidities are associated with the clinical outcome of the disease, which can vary from asymptomatic infection to more severe conditions. This disease can be manifested by acute complications, such as multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, ulcer/perforation of the digestive tract, coronary artery aneurysm, lymphomas and lymphohistiocytes, and EBV-associated hemophagocytosis.15,16

Mendoza et al.17 confirmed that the incubation period of the EBV infection ranges from 4 to 6 weeks. Prodromal symptoms include asthenia, anorexia, headache and chills often followed by the signs and symptoms of mononucleosis such as fever (up to 39–40 °C) with concomitant pharyngotonsillitis and lymphadenopathy.18,19 Also in the present study with 76 EBV-infected patients, the main clinical findings were fever (65.8%; 50/76), cervical lymphadenomegaly (61.8%; 47/76), arthralgia (17.1%; 14/76), and headache (21.0%; 16/76).

There are two different types of EBV,20 namely, type 1 and type 2 which are related to variations in the EBNA2 and EBNA3 gene sequences.13,21

Our findings demonstrated that EBV1 was the most frequent type (82.9%, 63/76) detected by PCR using the EBNA 3C gene in IM cases reported in the metropolitan region of Belém, Pará, Brazil, where 71.1% of cases (54/76) had EBV1 alone and 11.8% (9/76) associated with EBV2.

It is worth mentioning that the present study, obtained in symptomatic patients, is the first report on EBV types in this region. An investigation conducted in Chinese individuals using the same technique showed slightly lower rates of EBV1 (76.3%, 45/59).22 In this context, other studies carried out by Deng et al. (2014)23 in Japanese patients and by Smatti et al. (2017)24 in Qatar have also described EBV1 with rates of 73.3% (107/146) and 72.5% (37/51), respectively.

Our analyses, using multiple logistic regression model (MLR) showed that women were six-fold more likely to be infected by EBV1, in contrast to the findings of Correa et al.25 This detail can be explained by the fact that women stay longer in the household, where asymptomatic transmission can occur through saliva, direct oral contact or salivary residues left in food, glasses, toys, etc. Another passive form of transmission can be through sexual contact.

EBV2 was detected in 28.9% (22/76) of the positive EBV cases, with 17.1% monoinfection and 11.8% (9/76) in coinfections with EBV1 (Table 1). The rate of EBV2 was higher than those reported by Deng et al.,23 and Correa et al.,25 in Japan (18.5%, 27/146) and Argentina (14.6%, 29/199), respectively. Notably, EBV2 positivity rate in the age group comprising individuals aged 10–15 years old was much higher (62.5%, 5/8) than EBV1 positivity rate (25.0%, 2/8). However, these cases were detected in different months of the years in which testing was conducted.

In this investigation we showed that EBV2 infection had a longer clinical course than EBV1, with a mean duration of 17.6 days (range: 1–90 days) of fever for EBV2 compared to 14.7 days (range: 1–30 days) for EBV1. The in the EBV2-infected individuals aged 10–15 year had a high rate (62.5%) of fever and lymphadenopathy. EBV-2 has frequently been associated with specific clinical conditions in patients with weakened immune systems, such as HIV-infected persons with neoplastic diseases. In vitro, several studies have recorded a low frequency of EBV2 in B lymphocytes demonstrating a reduced or less efficient capacity for replication in cell cultures.13

The presence of coinfections by EBV1 + EBV2 was observed in 11.8% of the IgM positive cases of IM. Of those, 20.0% (2/10) were children less than five years old (Table 1). This finding emphasizes that coinfections are not limited to immunocompromised individuals. This association was also verified by Correa et al.,25 in 10.5% of healthy individuals who participated in a study conducted in Argentina. Coinfection may result from simultaneous transmission of both genotypes or by contact with two people infected with distinct strains.

Another notable finding of the present investigation was the elevations of hepatic enzymes (AST, ALT and GGT) levels. The proportion of individuals with these alterations varied from 19.4% to 41.7% (Table 3) among those with EBV1 in the age group over 14 years. These subjects showed increased levels of these enzymes, consistent with the findings of Herbinger et al.26

Small elevations in hepatic enzymes can occur in normal individuals without infection (less than twice the reference value), while in individuals with EBV-infective mononucleosis, these values can increase five to 10 times the upper limit and may even increase to levels indicating fulminate hepatitis.27

In addition, in this study the means of hepatic enzymes were significantly higher in EBV1-infected subjects aged 14 years and above (p < 0.05) compared to EBV2-infected or EBV1 + EBV2 coinfected subjects. Similar data have also been reported by Zhang et al.,28 comparing IM cases and controls, as they observed high levels of ALT, AST and GGT only in cases of IM, indicating that hepatic enzymes levels should also be observed as a risk alert in IM caused by EBV infection.

ConclusionIn this pioneering study, conducted from 2005 to 2016, the predominance of EBV1, the presence of EBV2 and the co-circulation of both types (EBV1 + EBV2) were observed. Additionally, the relevant clinical signs/symptoms of lymphadenopathy and fever and expressive enzymatic changes are described. This knowledge regarding the main EBV genotypes with local circulation can support the formulation of new clinical approaches, especially in cases of infectious mononucleosis that can evolve with a severe course. Determination of the types of EBV in the present study has enabled, for the first time, the ability to distinguish the molecular epidemiology and the circulation of these viral agents in individuals from northern Brazil

FundingThe authors received no specific funding for this work.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We are grateful to those who contributed to the development of this study, especially Antonio de Moura, Alessandra Alves Polaro and Dr. Manuel Gomes.