Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) can be caused by viruses, bacteria, and parasites. The World Health Organization estimated more than 300 million new global cases of curable STIs among individuals of reproductive age. Infection by Trichomonas vaginalis is one of the most prevalent curable STI. Despite the current treatments available, the diagnosis of T. vaginalis can be difficult, and the resistance to the treatment increased concern for the healthcare system.

ObjectivesThe aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and factors associated with Trichomonas vaginalis infection among women of reproductive age attending community-based services for cervical screening.

Patients and methodsA total of 1477 reproductive-aged women attending 18 Primary Health Care Units in Botucatu, Brazil, from September to October 2012, were enrolled. A structured questionnaire was used for individual face-to-face interviews for obtaining data on sociodemographic, gynecologic, and obstetrics history, sexual and hygiene practices, among others. Cervicovaginal samples were obtained for detection of T. vaginalis by culture using Diamond's medium and microscopic vaginal microbiota classification according to Nugent. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was carried out to estimate Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for the association between participants’ sociodemographic, behavioral factors, and clinical factors with T. vaginalis infection.

ResultsMedian age of study participants was 33 years (ranging from 18 to 50). The overall prevalence of T. vaginalis infection was 1.3% (n = 20). Several factors were independently associated with T. vaginalis infection, such as self-reporting as black or Pardo for ethnicity (OR = 2.70; 95% CI 1.03‒7.08), smoking (OR=3.18; 95% CI 1.23‒8.24) and having bacterial vaginosis (OR = 4.01; 95%CI = 1.55–10.38) upon enrollment. A protective effect of higher educational level (having high school degree) was observed (OR = 0.16; 95% CI 0.05‒0.53).

ConclusionsOur data suggest that screening programs to correctly detect T. vaginalis infection can be helpful to guide prevention strategies to the community. Our study supports an association between abnormal vaginal microbiota and T. vaginalis infection.

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) are caused by several microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria, and parasites that are transmitted primarily by vaginal, oral, or anal sexual contact.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States, the annual impact of STIs in 2018 on the North American healthcare system was nearly 16 billion in direct medical costs.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 374 million new global cases as one of the most common curable STIs among individuals from 15 to 49 years-old only in 2020. Of these, infection by Trichomonas vaginalis is the most prevalent curable STI accounting for nearly half of the cases (156 million).3 Despite the existing treatment regimens with antimicrobial drugs, infections by T. vaginalis are frequently a(oligo)symptomatic and diagnosis is not equally available worldwide, being particularly difficult in low resources regions.

T. vaginalis is a typically pyriform and occasionally amoeboid protozoan with primarily anaerobic metabolism that infects the genitourinary tract epithelium gender-independently.4 Due to its characteristic morphology, microscopy methods have been largely employed for diagnostic purposes, especially for scrutinizing status of culture of clinical samples in specific media. Most commonly reported signs and symptoms include dyspareunia and vaginal discharge, that may be diffuse, malodorous, or yellow green, with or without vulvar irritation. Also, in clinical examination cervical hemorrhagic punctate may be observed, which is often referred to as a “strawberry cervix”.5

Due to the occurrence of pelvic inflammatory disease6,7 and evidence that the infection reduces the viability of sperm, men and women may have reproductive consequences as a result of infection.8 Trichomoniasis may also impact the pregnancy course, causing low birth weight, premature rupture of membranes, and preterm delivery.9

Two population-based studies in the United States observed rates of 2.3% among adolescents10 and 3.1% among women with 14 to 49 years old.11 In Brazil, studies show that prevalence range from 2.6% to 20% in different settings,12–15 while the Brazilian Ministry of Health estimates an overall T. vaginalis prevalence of 15%.16

Several factors were already associated with the incidence of T. vaginalis infection such as younger ages, sexual activity, increased number of sexual partners, condom use, having other STIs, social demographic, and low economic conditions.2,3,17,18 Literature has also shown that T. vaginalis infection is associated with changes in the components of the vaginal microbiota, such as in bacterial vaginosis.19–24 Additionally, it was demonstrated that the presence of T. vaginalis infection increases susceptibility to the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).25

Studies of prevalence and risk factors for T. vaginalis infection are therefore of great importance to the health care system for the adoption of decisions and for the development of new guidelines for routine primary health care. Thus, this study aimed to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with the prevalence of T. vaginalis infection in reproductive-aged women in community-based clinics in southeast Brazil.

Materials and methodsStudy population and designThis cross-sectional study was carried out in Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil, from September to October 2012, and included a total of 1477 women of reproductive age who provided informed consent to participate in the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Board of Botucatu Medical School (UNESP), protocol 4121‒2012.

The community-based health system in Botucatu comprises 18 Primary Health Care Units which were the enrollment settings for the present study. Primary healthcare units are part of the Brazilian public health system and provide free medical care to the population of Botucatu. The reasons for consultation were 100% cervical screening program with or without genital symptom complaints.

The criteria for eligibility included women who were: non-pregnant, non-menopausal, no hysterectomy, no prior report of seroconversion for HIV, no antibiotic at least four weeks prior to the study or vaginal cream used in the preceding 30 days, and abstinence from sexual intercourse for 72 hours before the visit. A structured questionnaire containing 58 questions was administered by face-to-face interview to collect information on demographics characteristics, clinical history, and patients’ practices that predispose them to T. vaginalis infections was applied by trained nursing from Botucatu Medical School of São Paulo State University (FMB-UNESP). Following the interview, women were submitted to a gynecological examination. After inserting a non-lubricated speculum, routine pap smear was collected and cervical cytology was reported according to the Bethesda system. A sample from mid-vaginal wall was collected using a cotton swab to evaluate the vaginal microbiota pattern, and an additional sample from vaginal posterior fornix was taken to assess infection by T. vaginalis.

Detection of Trichomonas vaginalisInfection by T. vaginalis was examined by culture of vaginal posterior fornix samples in modified Diamond's medium at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Using a clean glass slide without cover and a sterile pipette, fresh wet-mount microscope slides were prepared with aliquots from the culture and examined microscopically under ×40 objectives.26 Presence of motile protozoan was checked daily, if it was not observed, the culture was incubated again with daily examination for up to 3 days in the same manner for the same trained observer. Whether T. vaginalis were not detected, the specimen was considered negative.

Microscopy evaluation of the vaginal microbiotaVaginal samples were spread onto glass microscope slides to classify vaginal microbiota following Gram-stain according to Nugent's scoring system: normal (scores 0‒3), intermediate (4‒6), and bacterial vaginosis (7‒10), regardless of the presence of symptoms or clinical findings.27 Vaginal candidiasis was based on the presence of yeast blastospores or pseudohyphae on the smears with accompanying inflammatory cells in the presence of vulvovaginal pruritus.28 All smears were evaluated by an experienced microscopist. All women with abnormal vaginal microbiota and/or positive for Candida spp. and T. vaginalis were treated in accordance with a protocol established by the Health Care Units of Botucatu.

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae testingFor the evaluation of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection by PCR, DNA extraction was obtained with a previous digestion with proteinase K. The presence and integrity of DNA samples were confirmed by the amplification of β-globin housekeeping gene using primers GH20 (GAA GAG CCA AGG ACA GGT AC) and PCO4 (CAA CTT CAT CCA CGT TCA CC) which target a 268-base pair sequence.29 To verify the presence of C. trachomatis infection in the sample, a multiplex PCR was performed using two pairs of specific primers. Primer pairs used were CTP1 (TAG TAA CTG CCA CTT CAT CA); CTP2 (TTC CCC TTG TAA TTC GTT GC) product site: 201 bp sequence, and PL6.1 (5′AGA GTA CAT CGG TCA ACG A 3′); PL6.2 (5′TCA CAG CGG TTG CTC GAA GCA 3′) product site: 130 bp sequence, using Taq DNA Polimerase (Platinum, Invitrogen®). Amplification parameters consisted of 40 cycles of 60 s at 95 °C, 60 s at 55 °C, and 90 s at 72 °C. In all reactions, negative and positive controls were run simultaneously, with respectively sterile water and C. trachomatis DNA extracted from infected McCoy cells.30 The evaluation of N. gonorrhoeae was performed with specific primers for PCR: HO1 (5′GCT ACG CAT ACC CGC GTT GC 3′) and H03 (5′CGA AGA CCT TCG AGC AGA CA 3′). PCR was performed using the Go Taq Green master mix (Promega Corporation, USA). Amplification parameters consisted of 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 60 s at 55 °C, and 30 s at 74 °C.31 Amplicon molecular weight was determined by comparing to a standard size marker, under UV transillumination.

Statistical analysisAll analyses were performed using Stata/SE 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics for continuous and categorical variables were performed utilizing non-parametric Mann-Whitney and test and Chi-Squared tests according to the status of T. vaginalis infection, with p-values <0.05 considered to be statistically significant. Crude univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for the association between covariates (sociodemographic, gynecologic and obstetrics history, sexual and hygiene practices, and others) and T. vaginalis infection. In addition, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed using a forward stepwise model (variables were retained at p-value ≤0.15) with positivity for T. vaginalis set as the dependent variable.

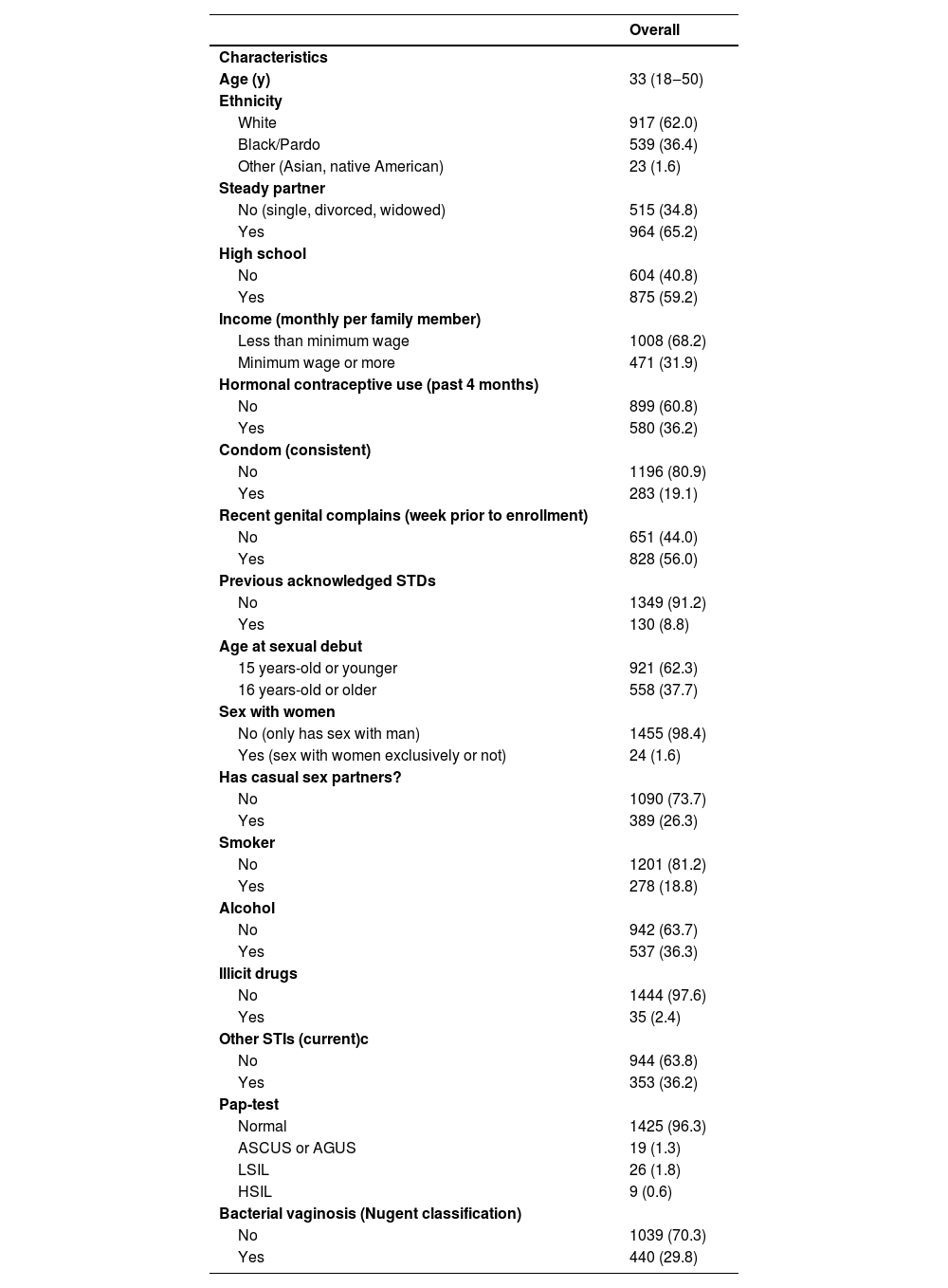

ResultsFor this study, 1477 women were enrolled and provided full data available for analysis. Median age of participants was 33 years old (ranging from 18 to 50); the majority self-defined their ethnicity as white (62.0%, n = 917) and most of the women were married or living in a steady partner (65.2%, n = 964). In relation to educational level, 59.2% (n = 875) had completed high school. Microscopic analysis of vaginal smears obtained upon study enrollment showed that bacterial vaginosis was detected in 29.8% (n = 440) of the study population (Table 1).

Sociodemographic, gynecological, and behavioral characteristics of patients according to their Trichomonas vaginalis infection status.

Continuous variables are displayed in median (range) and discrete variables in number (%). ASCUS, Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance; AGUS, Atypical Glandular cells of Undetermined Significance; LSIL, Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion; LSIL, High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial lesion.

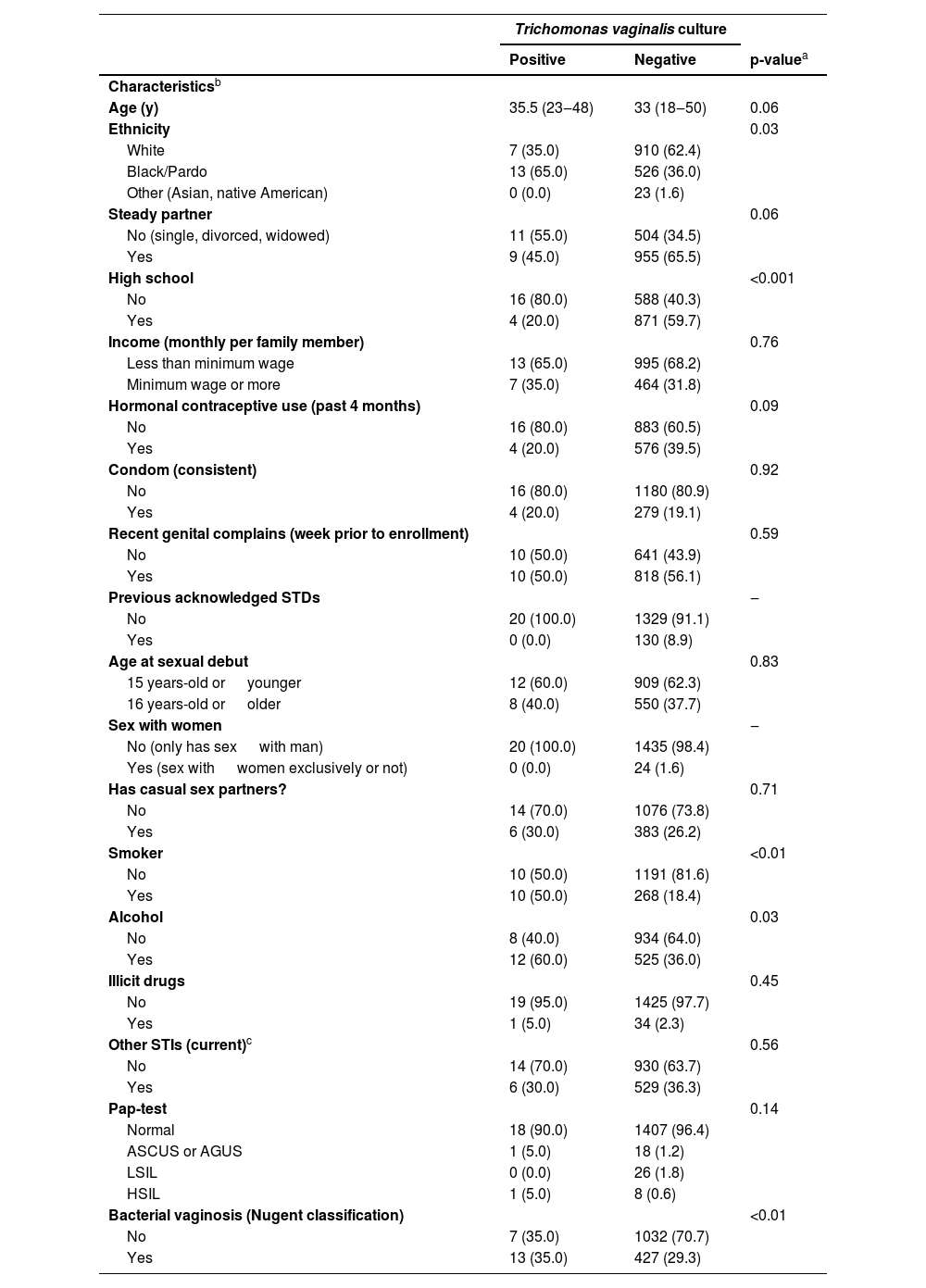

The reported prevalence of T. vaginalis was 1.3% (20/1477). Table 2 shows the results comparing population characteristics according to T. vaginalis status provided. Most of positive cases of T. vaginalis were observed among women that self-reported as black or Pardo (65.0%, n = 13), did not complete high school (80.0%, n = 16), presented habits as smoking in 50.0%, (n = 10) or alcohol consumption in 60.0% (n = 12), and had microscopic bacterial vaginosis at the time of enrollment was 35.0% (n = 13).

Sociodemographic, gynecological, and behavioral characteristics of patients according to their Trichomonas vaginalis infection status.

| Trichomonas vaginalis culture | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | p-valuea | |

| Characteristicsb | |||

| Age (y) | 35.5 (23‒48) | 33 (18‒50) | 0.06 |

| Ethnicity | 0.03 | ||

| White | 7 (35.0) | 910 (62.4) | |

| Black/Pardo | 13 (65.0) | 526 (36.0) | |

| Other (Asian, native American) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (1.6) | |

| Steady partner | 0.06 | ||

| No (single, divorced, widowed) | 11 (55.0) | 504 (34.5) | |

| Yes | 9 (45.0) | 955 (65.5) | |

| High school | <0.001 | ||

| No | 16 (80.0) | 588 (40.3) | |

| Yes | 4 (20.0) | 871 (59.7) | |

| Income (monthly per family member) | 0.76 | ||

| Less than minimum wage | 13 (65.0) | 995 (68.2) | |

| Minimum wage or more | 7 (35.0) | 464 (31.8) | |

| Hormonal contraceptive use (past 4 months) | 0.09 | ||

| No | 16 (80.0) | 883 (60.5) | |

| Yes | 4 (20.0) | 576 (39.5) | |

| Condom (consistent) | 0.92 | ||

| No | 16 (80.0) | 1180 (80.9) | |

| Yes | 4 (20.0) | 279 (19.1) | |

| Recent genital complains (week prior to enrollment) | 0.59 | ||

| No | 10 (50.0) | 641 (43.9) | |

| Yes | 10 (50.0) | 818 (56.1) | |

| Previous acknowledged STDs | ‒ | ||

| No | 20 (100.0) | 1329 (91.1) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 130 (8.9) | |

| Age at sexual debut | 0.83 | ||

| 15 years-old or younger | 12 (60.0) | 909 (62.3) | |

| 16 years-old or older | 8 (40.0) | 550 (37.7) | |

| Sex with women | ‒ | ||

| No (only has sex with man) | 20 (100.0) | 1435 (98.4) | |

| Yes (sex with women exclusively or not) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (1.6) | |

| Has casual sex partners? | 0.71 | ||

| No | 14 (70.0) | 1076 (73.8) | |

| Yes | 6 (30.0) | 383 (26.2) | |

| Smoker | <0.01 | ||

| No | 10 (50.0) | 1191 (81.6) | |

| Yes | 10 (50.0) | 268 (18.4) | |

| Alcohol | 0.03 | ||

| No | 8 (40.0) | 934 (64.0) | |

| Yes | 12 (60.0) | 525 (36.0) | |

| Illicit drugs | 0.45 | ||

| No | 19 (95.0) | 1425 (97.7) | |

| Yes | 1 (5.0) | 34 (2.3) | |

| Other STIs (current)c | 0.56 | ||

| No | 14 (70.0) | 930 (63.7) | |

| Yes | 6 (30.0) | 529 (36.3) | |

| Pap-test | 0.14 | ||

| Normal | 18 (90.0) | 1407 (96.4) | |

| ASCUS or AGUS | 1 (5.0) | 18 (1.2) | |

| LSIL | 0 (0.0) | 26 (1.8) | |

| HSIL | 1 (5.0) | 8 (0.6) | |

| Bacterial vaginosis (Nugent classification) | <0.01 | ||

| No | 7 (35.0) | 1032 (70.7) | |

| Yes | 13 (35.0) | 427 (29.3) | |

ASCUS, Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance; AGUS, Atypical Glandular cells of Undetermined Significance; LSIL, Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion; LSIL, High-grade Squamous intraepithelial Lesion.

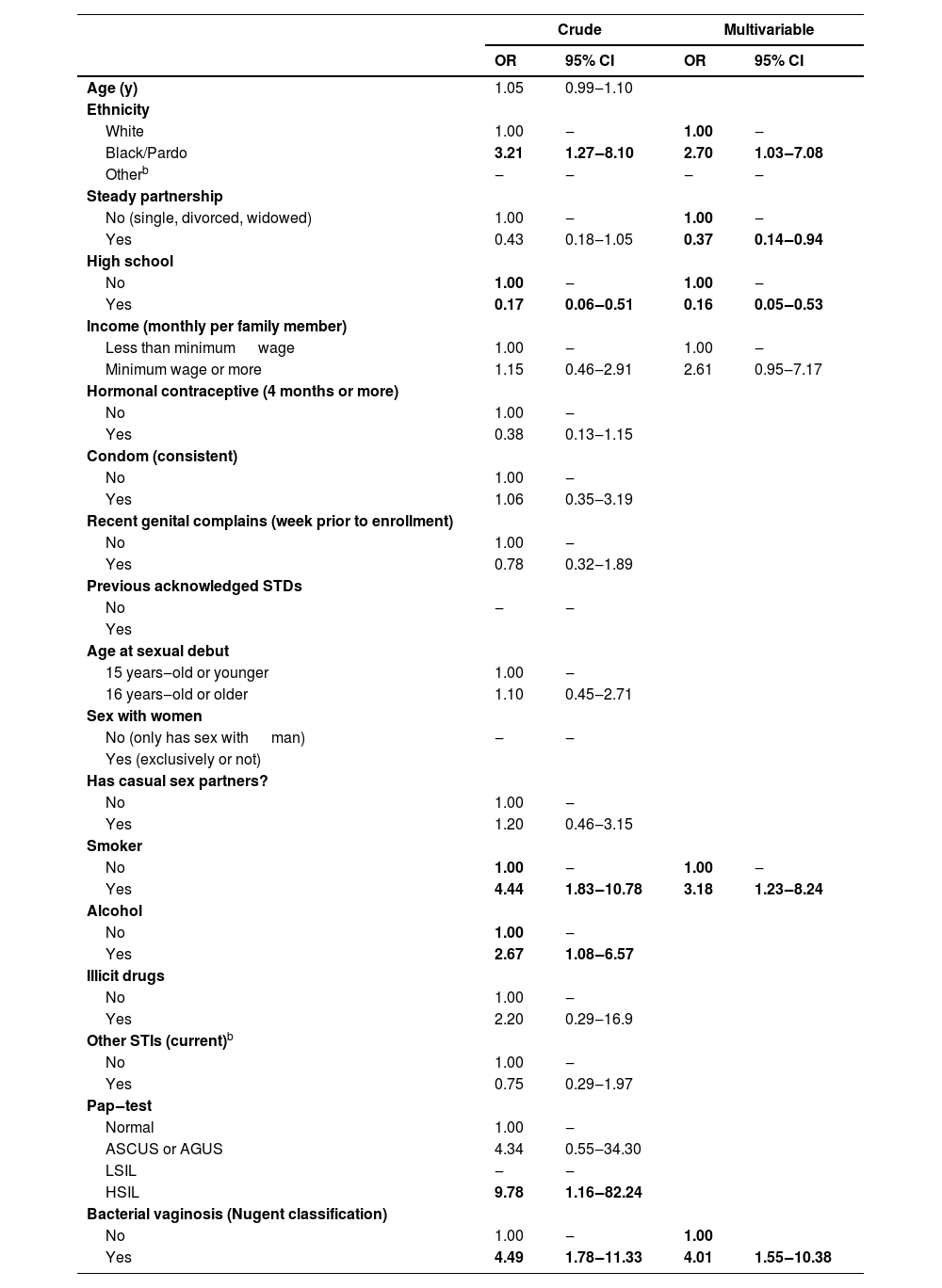

Sociodemographic characteristics, sexual behavior, and clinical history were calculated by the logistic regression model considering the T. vaginalis infection as the variable response, estimating each variable's effects as independent. While the prevalence of T. vaginalis was neither sociodemographic characteristics nor sexual behavior dependent (p > 0.05), abnormal microbiota was independently associated with the infection (OR = 4.49; 95% CI 1.78‒11.33) (Table 3). Also, in Table 3, race and ethnicity were categorized as white, black/Pardo and other (Asian, native American). Among all racial/ethnic groups combined, black/Pardo was associated with the infection in both models, univariable (OR = 3.21; 95% CI 1.27‒8.10) and multivariable (OR = 2.70; 95% CI 1.03‒7.08). Higher education level showed a protective effect also in the two models, univariable (OR = 0.17; 95% CI 0.06‒0.51) and multivariable (OR = 0.16; 95% CI 0.05‒0.53). In contrast, tobacco smoke was correlated with an increased risk of infection, univariable (OR=4.44; 95% CI 1.83‒10.78) and multivariable (OR = 3.18; 95% CI 1.23‒8.24). As a result of a multivariable analysis of T. vaginalis infection risk factors, being married or living with a partner proved to be protective compared to singles, divorcees, and widows.

Values of OR and 95% CI were obtained at univariate and multivariable stepwise logistic regression analysis for the population factors according to the status of Trichomonas vaginalis infection.

| Crude | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age (y) | 1.05 | 0.99‒1.10 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Black/Pardo | 3.21 | 1.27‒8.10 | 2.70 | 1.03‒7.08 |

| Otherb | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Steady partnership | ||||

| No (single, divorced, widowed) | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 0.43 | 0.18‒1.05 | 0.37 | 0.14‒0.94 |

| High school | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 0.17 | 0.06‒0.51 | 0.16 | 0.05‒0.53 |

| Income (monthly per family member) | ||||

| Less than minimum wage | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Minimum wage or more | 1.15 | 0.46‒2.91 | 2.61 | 0.95‒7.17 |

| Hormonal contraceptive (4 months or more) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 0.38 | 0.13‒1.15 | ||

| Condom (consistent) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.35‒3.19 | ||

| Recent genital complains (week prior to enrollment) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 0.78 | 0.32‒1.89 | ||

| Previous acknowledged STDs | ||||

| No | ‒ | ‒ | ||

| Yes | ||||

| Age at sexual debut | ||||

| 15 years‒old or younger | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| 16 years‒old or older | 1.10 | 0.45‒2.71 | ||

| Sex with women | ||||

| No (only has sex with man) | ‒ | ‒ | ||

| Yes (exclusively or not) | ||||

| Has casual sex partners? | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 1.20 | 0.46‒3.15 | ||

| Smoker | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 4.44 | 1.83‒10.78 | 3.18 | 1.23‒8.24 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 2.67 | 1.08‒6.57 | ||

| Illicit drugs | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 2.20 | 0.29‒16.9 | ||

| Other STIs (current)b | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| Yes | 0.75 | 0.29‒1.97 | ||

| Pap‒test | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 | ‒ | ||

| ASCUS or AGUS | 4.34 | 0.55‒34.30 | ||

| LSIL | ‒ | ‒ | ||

| HSIL | 9.78 | 1.16‒82.24 | ||

| Bacterial vaginosis (Nugent classification) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 4.49 | 1.78‒11.33 | 4.01 | 1.55‒10.38 |

ASCUS, Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance; AGUS, Atypical Glandular cells of Undetermined Significance; LSIL, Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion; LSIL, High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion.

aAsian, native American.

In this study we observed a prevalence of T. vaginalis infection of 1.3% and evidence for a 4-fold increased risk of T. vaginalis infection among women who had abnormal vaginal microbiota. The prevalence found here was similar to observed in other studies in Brazil and worldwide.32–35 Additionally, sociocultural characteristics should also be considered as different across different populations.36

To establish the infection, T. vaginalis must mediate contact with epithelial cells, adhere to, and lyse host epithelial cells, causing tissue damage, generated by a strong infiltration of leukocytes and by high local concentrations of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines.37 Immune responses during infection cause inflammation, which can also contribute to disease establishment, however, T. vaginalis has host immunity evasion mechanisms. Subsequently, the parasite lives associated with the vaginal microbiota, leading to pathogenic ruptures of vaginal bacteria.38 Bacterial vaginosis, a microbiome-disturbance prevalent in reproductive-age women, is characterized by a shift from a Lactobacillus-dominated to a diverse polymicrobial state, with pro-inflammatory features, combined with an immune response driven by individual variability in the host immune system,39 and occurs commonly in concert with trichomoniasis, and its interaction has been suggested.24

The relation between vaginal microbiota and T. vaginalis infection observed in this study corroborates with others.40–42 Although several studies have reported an increased risk of T. vaginalis acquisition among women with bacterial vaginosis, the precise nature of the relationship between the role of T. vaginalis infection in the susceptibility to an unbalance in the vaginal microbial, or even the opposite, a previous imbalance of the microbiota that would favor infection by the protozoan is not well understood.

More longitudinal cohort studies are needed, using accurate detection techniques to demonstrate cause and consequence between vaginal microbiota and T. vaginalis infection. As demonstrated, women experiencing abnormal microbiota during a three-month span appear to have significantly increased risk of acquiring T. vaginalis infection.42

Prevalence of T. vaginalis infection in this study did not differ by economic status, but higher prevalence has been consistently reflected in women who did not complete high school in comparison to having at least completed high school, as demonstrated by Patel et al.,43 and a positive association with infection in participants with lower level of education was demonstrated in previous study.44 The importance of identifying the demographic characteristics of populations at higher risk for acquire STIs may impact the need for effective educational strategies, screening of groups at higher risk and treatment for infected people and sexual partners.

The risk factors for T. vaginalis infection and the prevalence in our study were similar to those observed by Tompkins et al.45 Our studies found risk factors that representing behavioral habits such as smoking were more likely to be infected with T. vaginalis, as compared to non-smokers.

According to our results, the infection rate of T. vaginalis suggests that screening programs to detect this infection could be helpful in establishing prevention strategies in our population. Our study supports an association between abnormal vaginal microbiota and T. vaginalis infection.

Author contributionsGVSP contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data analysis, writing.

ANB contributed to investigation LFM contributed to investigation NPM contributed to investigation BRAR contributed to investigation.

MDCS contributed to investigation, writing, reviewing and edition MTCD contributed to investigation, writing, reviewing, and edition ART contributed to investigation, writing, reviewing and edition.

MGS contributed to supervision, conceptualization, writing, editing, reviewing, and funding.

CM contributed to supervision, conceptualization, writing, editing, reviewing, and funding.

FundingThis study was supported by: developmental funds granted by São Paulo Research Foundation − FAPESP (Grant 2012/01278-0) granted to Dr. Márcia Guimarães da Silva from the Department of Pathology, Botucatu Medical School, UNESP − Univ. Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil; and by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES (88881.132503/2016-01) granted to Gabriel Vitor da Silva Pinto, Master student in the Post-graduate Program in Pathology, Botucatu Medical School, UNESP − Univ. Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil. This work was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brazil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.