Clostridium difficile infections caused by the NAP1/B1/027 strain are more severe, difficult to treat, and frequently associated with relapses.

MethodsA case–control study was designed to examine a C. difficile infection (CDI) outbreak over a 12-month period in a Mexican hospital. The diagnosis of toxigenic CDI was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction, PCR (Cepheid Xpert C. difficile/Epi).

ResultsDuring the study period, 288 adult patients were evaluated and 79 (27.4%) patients had confirmed CDI (PCR positive). C. difficile strain NAP1/B1/027 was identified in 31 (39%) of the patients with confirmed CDI (240 controls were included). Significant risk factors for CDI included any underlying disease (p<0.001), prior hospitalization (p<0.001), and antibiotic (p<0.050) or steroid (p<0.001) use. Laboratory abnormalities included leukocytosis (p<0.001) and low serum albumin levels (p<0.002). Attributable mortality was 5%. Relapses occurred in 10% of patients. Risk factors for C. difficile NAP1/B1/027 strain infections included prior use of quinolones (p<0.03).

Risk factors for CDI caused by non-027 strains included chronic cardiac disease (p<0.05), chronic renal disease (p<0.009), and elevated serum creatinine levels (p<0.003). Deaths and relapses were most frequent in the 027 group (10% and 19%, respectively).

ConclusionsC. difficile NAP1/BI/027 strain and non-027 strains are established pathogens in our hospital. Accordingly, surveillance of C. difficile infections is now part of our nosocomial prevention program.

Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) are the leading worldwide cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea and in some countries CDI surpass all other healthcare-associated infections (HCAI).1 A recent prevalence survey of HCAI conducted across 183 hospitals determined that C. difficile was the most frequently reported infectious agent, responsible for 12.1% of all HCAI.1

In the United States of America (USA) during 2011, 15,461 CDI cases were reported with 24.2% of cases having an onset during hospitalization. Incident CDI cases were estimated to be >450,000 with an estimated >29,000 deaths.2 However, the emergence of the C. difficile NAP1/B1/027 strain in 2000 changed the morbidity and mortality rates associated with CDI.3,4

Since 2004, the role of other emergent C. difficile strains causing human disease has expanded. These strains are derived from 39 different ribotypes and some C. difficile strains have been found to be toxin A-negative but toxin B-positive,5 and 027 strain was the second most common isolate responsible for CDI.6 Ribotype 078 was reported to have an increased prevalence,7 and ribotype 244 seems to cause more severe disease with higher mortality rates than rates associated with ribotype 027.8,9 The prevalence of other ribotypes now appears to surpass that of 027, including ribotypes 037, 018, and 078.10–12

Epidemiologic research of CDI resulting from infections with diverse C. difficile strains, including strain NAP1/B1/027 in developing countries, is expanding and includes data regarding hospital epidemiology, clonal spread, and dissemination across the respective countries.13–16

The present study reports on a 12-month evaluation of a CDI outbreak caused by different C. difficile strains including the NAP1/BI/027 strain.

MethodsSetting, study design, and study populationThe outbreak described in this report occurred at the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde, an 899-bed tertiary care teaching hospital located in the city of Guadalajara, the second largest city in Mexico.

This was a case–control study of adult patients with hospital-onset CDI presenting between December 2013 and December 2014. During the study period 288 adult patients were evaluated and all patients had diarrhea defined as the passage of ≥3 unformed stools (Bristol scale type 5–7) within 24 or 48h after admission.17 Case patients were defined as those with a first episode of nosocomial CDI.

Clostridium difficile toxin identificationStarting in April 2014, all stool samples were tested for C. difficile toxins using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Cepheid Xpert C. difficile/Epi, Cepheid, Sunnyvale CA) to identify toxin-producing C. difficile strains, including strain NAP1/B1/027. Prior to the availability of PCR-based diagnostic approaches all diarrhea specimens were tested by enzyme immunoassay (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH, USA). All positive specimens were saved for future testing. All stool specimens were stored at 4°C for five days, and then frozen at −70°C. After PCR retesting, only positive samples were included in the final analysis.

Control patientsPatients without diarrhea or a positive CDI test were selected at the same time and ward that CDI patients were identified. Control patients were randomly selected across the study period. Control patients were matched to case patients at a 3:1 ratio.

DefinitionsPrevious hospitalization was defined as a hospital stay six weeks prior to the onset of diarrhea. Recent antibiotic therapy and steroid use were defined as exposure to these medicines six weeks prior to diarrhea onset.

Clinical severity score assessment and outcomePatients were clinically evaluated for disease severity using the SHEA/IDSA definitions of mild, moderate, or severe disease. Serum creatinine levels were included in the definition of severe disease.18 In addition, age >60 years, fever >38.3°C, and a WBC count >15,000 were used to further define clinically severe disease.19 Patients with >2 findings were considered to have severe disease.

A poor outcome was defined as death within 14 days after CDI diagnosis. Favorable outcome was defined by survival 14 days after CDI diagnosis. Relapse was defined as a second episode of diarrhea after adequate response to therapy.

Therapy and follow-upTherapy for CDI was administered for 10 days after an adequate response to treatment was achieved (defined as a 50% reduction of loose stools after 24h of therapy, continuous reduction after 48h of treatment, and no diarrhea after 72h of treatment). All patients discharged where followed via telephone every 30 days.

Statistical analysisThe data generated were coded, entered, validated, and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 22.0. Univariate analyses were used to describe significant variables among cases and controls and among individuals infected with strain 027 and individuals infected with non-027 strains. P-values were calculated using the Chi-squared test or the Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis: logistic regression analysis was carried out considering CDI as dependent variable and clinical and demographic data as independent variables.

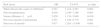

ResultsStudy populationThe age range of CDI patients and controls were similar (Table 1). Patients >65 years of age were the minority in both groups (Table 1). There was no gender difference between cases and controls; however, males were more frequently affected with CDI than females (Table 1). The presence of any underlying disease was an important risk factor for acquiring CDI, especially a previous episode of pneumonia or the presence of chronic renal disease (Table 1). Additional risk factors associated with CDI included prior hospitalization, antibiotic or steroid use, and elevated white blood cell counts (>12,000/mm3) combined with low serum albumin levels (<3g/dl) (Table 1). Four (5%) patients died in the CDI group and 8 (10%) relapsed (Table 1). The incidence of CDI was 1.7 per 1000 discharges.

Characteristics of CDI patients and controls, severity, outcomes, relapses, and clinical aspects of patients infected with 027 and non-027 strains.

| Parameters | CDI patients (n=79)n (%) | Controls (n=240)n (%) | p-value | 027 strain (n=31)n (%) | Non-027 strain (n=48)n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||||

| 18–30 | 23 (29.1) | 62 (25.8) | 0.28 | 7 (23) | 16 (34) | 0.22 |

| 31–50 | 24 (30.4) | 88 (36.7) | 0.15 | 11 (35) | 13 (27) | 0.29 |

| 51–65 | 21 (26.6) | 53 (22.1) | 0.20 | 10 (32) | 12 (25) | 0.32 |

| >65 | 11 (13.9) | 37 (15.4) | 0.38 | 3 (10) | 7 (14) | 0.39 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 51 (64.5) | 148 (61.7) | 0.32 | 21 (67.7) | 30 (62.5) | 0.40 |

| Female | 28 (35.5) | 92 (38.3) | 0.32 | 10 (32.3) | 18 (37.5) | 0.40 |

| Underlying disease | ||||||

| Any | 73 (92.4) | 170 (70.8) | <0.001 | 27 (87.1) | 46 (95.6) | 0.15 |

| Malignancy | 11 (13.9) | 18 (7.5) | 0.142 | 6 (19.3) | 5 (10.4) | 0.21 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (25.3) | 51 (21.3) | 0.27 | 5 (16.1) | 15 (31.3) | 0.10 |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 22 (27.8) | 49 (20.4) | 0.112 | 5 (16.1) | 17 (35.4) | 0.05 |

| Chronic hepatic disease | 2 (2.5) | 5 (2.0) | 0.55 | 0 | 2 (4.2) | 0.36 |

| Previous episode of pneumonia | 16 (20.2) | 16 (6.7) | 0.005 | 5 (16.1) | 11 (22.9) | 0.33 |

| Chronic renal disease | 23 (29.1) | 43 (17.9) | 0.027 | 4 (12.9) | 19 (39.6) | 0.009 |

| Healthcare-associated exposure | ||||||

| Prior hospitalization | 43 (54.4) | 57 (23.8) | <0.001 | 20 (64.5) | 23 (47.9) | 0.11 |

| Prior surgery | 44 (55.7) | 117 (48.8) | 0.173 | 17 (62.9) | 27 (56.3) | 0.54 |

| Prior antibiotics | ||||||

| Any | 58 (73.4) | 150 (62.5) | 0.050 | 23 (74.2) | 35 (72.9) | 0.55 |

| Betalactams | 43 (54.4) | 108 (45) | 0.155 | 17 (54.8) | 30 (62.5) | 0.32 |

| Quinolones | 16 (20.3) | 31 (12.9) | 0.142 | 9 (39.13) | 5 (10.4) | 0.03 |

| Clindamycin | 10 (12.7) | 38 (15.8) | 0.313 | 4 (17.39) | 6 (12.5) | 0.60 |

| Prior use of acid suppressing medication | ||||||

| Proton pump inhibitors | 67 (84.8) | 192 (80.0) | 0.21 | 25 (80.65) | 42 (87.5) | 0.30 |

| H2 blocker | 5 (6.3) | 18 (7.5) | 0.47 | 1 (3.23) | 4 (8.3) | 0.34 |

| Prior use of steroids | 17 (21.5) | 16(6.7) | <0.001 | 8 (25.8) | 9 (18.8) | 0.31 |

| White blood cells count >12,000/mm3 | 37 (46.8) | 63 (26.3) | <0.001 | 15 (48.4) | 22 (45.8) | 0.50 |

| Serum creatinine ≥1.5mg/dl | 22 (27.8) | 53 (22.1) | 0.20 | 3 (9.7) | 19 (39.6) | 0.003 |

| Serum albumin <3g dl | 46 (58.2) | 91 (37.9) | <0.002 | 18 (58.1) | 28 (58.3) | 0.58 |

| Initial Clinical Severity Score ≥2 | 69 (87.3) | – | – | 28 (90) | 41 (85) | 0.39 |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Poor/death | 4 (5) | – | – | 3 (10) | 1 (2) | 0.16 |

| Good/cured | 75 (95) | – | – | 28 (90) | 47 (98) | 0.16 |

| Relapses | 8 (10) | – | – | 6 (19) | 2 (4) | 0.03 |

Strain NAP1/B1/027 was identified in 31 (39%) patients with CDI. There were some differences between CDI resulting from infections with strain 027 and non-027 strains. The presence of chronic cardiac disease and chronic renal disease were found to be significantly more frequent in the non-027 group (Table 1). Although both groups had a similar initial severity score, more deaths and relapses were associated with strain 027 infections (Table 1). Additional risk factors associated with 027 and non-027 infections were prior use of quinolone and abnormal serum creatinine level (>1.5mg/dl), respectively (Table 1).

Logistic regression analysis included the significant risk factors for CDI prior use of steroids, a previous episode of pneumonia, and prior hospitalization (Table 2). Also identified abnormal white blood cell count and low serum albumin levels as independent risk factors for acquiring CDI (Table 2).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for CDI.

| Risk factor | OR | CI 95% | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells count >12,000/mm3 | 2.541 | 1.414–4.567 | 0.002 |

| Prior hospitalization | 4.029 | 2.240–7.246 | 0.001 |

| Serum Albumin <3g dl | 2.026 | 1.138–3.608 | 0.016 |

| Previous episode of pneumonia | 4.251 | 1.848–9.779 | 0.001 |

| Prior use of steroids | 5.077 | 2.203–11.698 | 0.001 |

The CDI outbreak described in this report occurred following introduction of the C. difficile 027 strain into our hospital by a patient diagnosed in December 2013. This individual had had multiple healthcare contacts in the USA (including several due to diarrhea) prior to being admitted to our neurosurgical ward. Introduction of C. difficile into a hospital will usually develop into an outbreak and previous studies have documented outbreaks following detection of strain 027.3,4,20

Other Latin American countries from Central and South America have now described the presence and dissemination of C. difficile.15,21 The C. difficile dissemination pattern seen in Mexico was similar to that described in hospitals in the USA and Canada, but different from that of the European Union where C. difficile 027 is not yet as prevalent. The appearance, establishment, and dissemination of C. difficile in Mexico seemed to occur in large referral hospitals where a high percentage of patients admitted had multiple risk factors for CDI.14,22

The presence of a serious underlying disease is a frequent risk factor for the development of CDI23 and the presence of any underlying illness (particularly a previous episode of pneumonia) was a significant risk factor in patients compared to controls.

In our population, community acquired pneumonia was diagnosed most frequently in older patients with comorbidities including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These patients typically had multiple previous healthcare exposures including prior hospitalizations allowing for a greater probability of acquiring C. difficile. Because current guidelines of our hospital recommend administration of quinolones as empiric treatment for pneumonia24 this patient group had been exposed to this drug.

A frequent risk factor in our study included patients with chronic renal disease. Since our hospital is a regional center for the diagnosis and care of patients in need of renal replacement therapy or a renal transplant it is responsible for a large population that is affected by this underlying illness.25 Similar to patients with other chronic diseases, patients with chronic renal disease have multiple healthcare contacts (including dialysis) and have multiple previous antibiotic exposures due to empiric or definitive treatment of different infectious diseases complications, including peritonitis resulting from peritoneal dialysis. Concomitant administration of steroids occurs frequently when patients have serious comorbidities and need assistance in the treatment of various complications.

The clinical features found in our CDI patients included an increased white blood cell count, elevated serum creatinine and reduced serum albumin levels. These findings are the basis for most clinical prediction rules used today.18,19,26–29 Patients presenting with severe CDI typically were older and had an increased number of bowel movements, had a history of systemic antibiotic use, and presented with fever, abdominal distention, abnormal respiratory rate, abnormal level of C-reactive protein, prior episodes of CDI, increased white blood cell count, elevated serum creatinine level, and low serum albumin level.18,19,26–29 Using these clinical prediction rules most of our patients had severe CDI.

The use of clinical prediction rules in CDI are also used to determine individuals at risk of having poor outcomes or a relapse.28,30–34 The most prominent factor predictive of a poor outcome or relapse among CDI patients described in this report was infection with strain 02735 and chronic renal disease.

After eliminating confounders, independent risk factors for CDI included prior use of steroids, previous episodes of pneumonia, and prior hospitalizations (Table 2). The epidemiology of C. difficile infections is constantly changing and probably explains some of the differences found in our study compared with previous observations made in Mexico.14,22,36

The diagnosis of CDI was primarily carried out using a commercial PCR kit, a test that has high sensitivity and specificity but with several limitations, including the inability of this test to identify emergent C. difficile variants.9,37,38

The choice for initial empirical therapy in our study consisted of metronidazole. Other therapeutic choices included administration of oral vancomycin as opposed to intravenous administration combined with either intravenous metronidazole or intravenous tigecycline based on individual response to oral metronidazole.39,40

In an effort to control the outbreak our intervention program focused on identifying CDI cases as quickly as possible, providing early treatment, isolating CDI cases in a dedicated ward, and restricting all quinolone use.41–43 The presence of a disease such as CDI that is transmitted via oral-fecal contamination prompted us to reevaluate patient hand washing practices prior to each meal or the intake of oral medication, in addition to assessing hand washing practices of the staff assigned to help feed patients. This resulted in the implementation of an aggressive patient hand washing campaign.

All patients discharged after an episode of CDI received careful instructions on how to proceed should a relapse occur.44 The instructions included a description of some of the symptoms that may present during a relapse, where to get medical attention, and what to inform healthcare personnel on arrival to clinics.

The present study had several limitations including the lack of C. difficile cultures to enable typing, limited use of a computed tomography scan for abdominal radiographic imaging prior to colonoscopy, colonoscopy for diagnosis of CDI, follow-up PCR testing was used only in select patients,45 and no autopsies were performed.

In conclusion, the control of CDI in our hospital now represents a constant challenge. The control of CDI in a hospital like ours should include a tailored strategy designed to identify cases of CDI as rapidly as possible. This study represents the first description of an extended CDI outbreak caused by diverse C. difficile strains including the NAP1/B1/027 strain in a Mexican hospital.

FundingNo funding was received for this work.

Ethical approvalThis study was performed with the approval of the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent approved by the Ethics Committee was obtained from all patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Members for the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, Fray Antonio Alcalde Clostridium difficile Team were: Leon-Garnica G, Castillo-Mondragon A, Camacho-Rubio JR, Rodriguez-Nuñez AJ, Mendoza-Mujica C, Heredia-Cervantes J, Mata-Esteban RA, Llamas-Alonso J, Lucio-Figueroa JO, Macias-Hernandez KZ, Macías-Bolaños DJ. Cardenas-Lara FJ, Fernandez-Ramirez A (Instituto de Patologia Infecciosa y Experimental, Centro Universitario Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Guadalajara), Vazquez-León M, Gomez-Quiroz P. (Infectious Diseases Unit Attendings), Eduardo Ortigosa-Medrano, Gomez-Gomez K, Vargas-Garcia LF (Infectious Diseases Unit Fellows) Gutierrez-Martinez ES, Garcia-Reyes MG, Zamora-Morales S, Casillas-Pacheco MA, Martinez-Cardona L, Magaña-Ibarra S. Tello G. (Epidemiology) Rodriguez-Chagollan JJ, Anguiano-Gaytan G, Atilano-Duran MCG, Llanos-Perez E, Gomez-Quiroz A, Zavala M (Microbiology).

Members for the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, Fray Antonio Alcalde Clostridium difficile Team were given in Appendix A.