Herein we report the case of a 10-year-old boy with an autosomal mosaic mutation who developed bacteremia. The causative agent was identified as Moraxella osloensis by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. In the pediatric population, there have been 13 case reports of infection attributed to M. osloensis and this is the fifth reported case of pediatric bacteremia due to M. osloensis. After Moraxella species infection was confirmed, the patient recovered with appropriate antimicrobial therapy. It is important to consider that M. osloensis can cause serious infections, such as bacteremia, in otherwise healthy children.

Moraxella osloensis is an aerobic, Gram negative coccobacillus. It can be isolated from healthy human respiratory tracts, but has been reported as a rare pathogen in immunocompromised individuals, like patients with cancer, leukemia, and organ transplant recipients.1 However, it is not well known as a pediatric pathogen. Here, we report a pediatric case of bacteremia due to M. osloesnis, with a partial review of the literature.

Case reportThe patient was 10-year-old boy with an autosomal mosaic mutation [46XY,t(9;15)(p22;p13),46XY,der(9)t(9;15)(p22;p13)]. He had mild intellectual disability and a substantial history of infectious diseases, including pneumonia, otitis media, sinusitis, and urinary tract infection due to Escherichia coli. He received prophylactic trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole until six years of age. His immune function was normal, including number of neutrophils, immunoglobulins, and complement. In recent years, he had been doing well without medication.

The patient visited Kofu Municipal Hospital with a 10-day history of fever, cough, and sore throat, and he had been treated with oral cephem antibiotics for a few days before presentation. On physical examination, his temperature was 40°C, and his throat was found to be infected. Laboratory testing revealed the following: white blood cell count 6400/μL (77% neutrophils, 17% lymphocytes, and 15% monocytes), hemoglobin 14.0g/dL, platelet count 19.9×104/μL, C-reactive protein level 1.8mg/dL, IgG 1050mg/dL (IgG1 600mg/dL, IgG2 326mg/dL, IgG3 30.6mg/dL, and IgG4<3.0mg/dL), IgA 101mg/dL, and IgM 71mg/dL. Urinalysis was normal and rapid influenza A and B antigen tests were negative. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography findings were normal. He received ambulatory care for acute pharyngitis after blood and a throat swab for culture were obtained. Two days later, a Gram negative coccobacillus was isolated from blood culture. The patient, who still had fever and fatigue, was admitted to the hospital for Gram negative bacteremia. Intravenous meropenem (100mg/kg/day) was administered as an empirical treatment. The patient became afebrile after treatment, and his other symptoms improved. On day 2, Moraxella species were isolated from blood culture, but precise identification was not obtained with our BD Phoenix system (BD Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The isolate was determined to be susceptible to ampicillin, piperacillin, cefazolin, cefotaxime, gentamicin, levofloxacin, meropenem, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, a cefinase test found the isolate positive for β-lactamase. We switched to ceftriaxone (120mg/kg/day) until discharge on day 10 when a repeated blood culture was sterile. The throat culture did not yield Moraxella species.

The organism in this case was finally identified as M. osloensis by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Biotyper). Its identity was confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Namely, 16S rRNA gene fragments were amplified by PCR using universal primers 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and 5′-CTTGTGCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC-3 (Y is C or T and H is A, C, or T) and 55°C annealing temperature.2 PCR amplicon was purified with a Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean Up system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and sequenced directly on both strands with a BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an ABI 3730xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The 1308-bp nucleotide sequence obtained had 100% sequence identity to the corresponding sequence of M. osloensis (accession no. AB931117) by analyzing with Ribosomal Database Project II (release 11, update 5) (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/index.jsp).

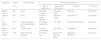

DiscussionM. osloensis was first described by Bövre in 1947 and has been isolated in various environments, including hospitals. In the pediatric population, there have been 13 case reports of infection attributed to M. osloensis including four cases of bacteremia (Table 1). This is the fifth reported case of pediatric bacteremia due to M. osloensis, to the best of our knowledge. In contrast to older patients, the majority of these infections were found in patients that did not have underlying medical conditions.

Clinical characteristics of Moraxella osloensis bacteremia in children.

| Reference | Age(y) | Clinical History | Clinical manifestation(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Without bacteremia | Approach for identification | Treatment | Outcome | ||

| Butzler et al.6 | 2/M | None | Stomatits, Impetigo | Laboratory culture | Ampicillin | Recovered |

| Shah et al.1 | 2/M | None | Reactive airway disease | Laboratory culture | Cefloxime, ST | Recovered |

| Dien Bard et al.7 | 3/M | Cortical dysplasia and developmental delay | Prolonged hypotension | 16S rRNA | Piperacillin/tazobactam | Recovered |

| Minami et al.8 | 9/M | Cerebral palsy | Possible cholecystitis | 16S rRNA | Cefmetazole | Recovered |

| Present patient | 10/M | Mild intellectual disability | Prolonged fever | MALDI-TOF MS, 16S rRNA | Meropenem, ceftriaxone | Recovered |

M, male; ST, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; 16S rRNA, 16S rRNA gene sequencing; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry.

The appropriate treatment for invasive M. osloensis infection has not been studied. Most reported isolates have been susceptible to penicillin and cephalosporins, but penicillin-resistant strains of M. osloensis (minimum inhibitory concentration of 6.25μg/mL) have been reported.3 Among Moraxella species, M. catarrhalis, M. lacunata, and M. nonliquefaciens are known to produce BRO β-lactamase, which degrades penicillin and a part of first-generation cephalosporin.4 It remains to be clarified whether or not M. osloensis produces BRO β-lactamase. We chose ceftriaxone as a definitive therapy because of its performance against BRO β-lactamase and effectiveness against other Moraxella species.

M. osloensis is difficult to identify because of the presence of several other species with similar phenotypic characteristics.5 MALDI-TOF MS is a tool for rapid, accurate, and cost-effective identification of cultured bacteria and fungi based on automated analysis of the mass distribution of bacterial proteins. The organism in this case was identified by this method and confirmed furthermore by 16SrRNA sequence analysis, which is the most reliable method for species-level identification.

Herein we report a rare pediatric case of bacteremia caused by M. osloensis. The patient recovered with antimicrobial therapy, but it is important to consider that M. osloensis can cause serious infections, such as bacteremia, in otherwise healthy children.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 17K10104).

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.