Antiretroviral therapy for HIV has led to increased survival of HIV-infected patients. However, tuberculosis remains the leading opportunistic infection and cause of death among people living with HIV/AIDS. Tuberculosis has been shown to be a good predictor of virological failure in this group. This study aimed to evaluate the incidence of tuberculosis and its consequences among individuals diagnosed with virological failure of HIV. This was a retrospective cohort study involving people living with HIV/AIDS being followed-up in an AIDS reference center in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Individuals older than 18 years with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy for at least six months, diagnosed with virological failure (HIV-RNA greater than or equal to 1000copies/mL), from January to December 2013 were included. Tuberculosis was diagnosed according to the criteria of the Brazilian Society of Pneumology. Fourteen out of 165 (8.5%) patients developed tuberculosis within two years of follow-up (incidence density=4.1 patient-years). Death was directly related to tuberculosis in 6/14 (42.9%). A high incidence and tuberculosis-related mortality was observed among patients with virological failure. Diagnosis of and prophylaxis for tuberculosis in high-incidence countries such as Brazil is critical to decrease morbidity and mortality in people living with HIV/AIDS.

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has led to increased survival among HIV-infected patients and improved the quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).1 However, tuberculosis (TB) remains the most common opportunistic infection and a leading cause of death among patients with HIV, particularly in sub-Saharan African and Asian countries, where it is highly prevalent.2,3 Worldwide, it is estimated that there were 9.0 million new TB cases in 2013, 13% of whom were PLWHA.2 In Brazil, 73,000 new TB cases were detected, and 4577 deaths occurred in 2013.4 In Bahia, a northeastern state of Brazil, the incidence of TB is decreasing slowly, and it is the state with the fourth largest number of TB cases in Brazil.5

An estimated 36.7 million people are living with HIV worldwide and of these, 17 million are using antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 In Brazil, it is estimated that approximately 798,000 people were living with HIV in 2014, a prevalence of 0.39%. Of these, approximately 405,000 PLWHA were on ART, and 356,000 (88%) of them presented with viral suppression at least six months after initiation of antiretroviral therapy.6

The risk of TB in HIV-infected patients and the impact of TB diagnosis on disease progression in HIV-infected patients have been well described in Africa.3,7 It is known that PLWHA once infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis have a risk of developing overt TB of approximately 5–10% per annum, higher than for the general population8; moreover, TB may occur at any stage of HIV infection. The management of HIV infections in persons with TB is complicated by several factors, including drug interaction, overlapping drug toxicities, exacerbation of side effects, concerns about adherence, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).9 Some studies suggest that virological failure is more likely to ensue in patients diagnosed with TB after starting ART therapy develop, suggesting that it is a result of the above-mentioned factors associated with double infection.10–12

Although the success rates of ART are considered high, other factors may be associated with the occurrence of virological failure. Singh et al.12 and Tran et al.13 pointed to TB as a predictor of virological failure, as well as the most frequent opportunistic infection among individuals who change ARV regimens.

Currently, early initiation of ART is recommended, but this strategy can potentially increase the risk of HIV resistance.6,14 This underscores the importance of virological monitoring in the clinical treatment routine. Early recognition of virological failure and TB control is critical to minimize the consequences of partial or incomplete viral suppression. Few studies have shown the occurrence of TB associated with virological failure. This study aimed to evaluate the incidence of TB and its consequences among individuals diagnosed with virological failure of HIV.

This is a retrospective cohort study involving PLWHA followed in the State Center Specialized in Diagnosis, Care, and Research (CEDAP), the largest reference center for treatment of PLWHA in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, where 3200 HIV/AIDS patients are under therapy. We included patients over 18 years of age, with a confirmed diagnosis of HIV infection, who were diagnosed with virological failure in the period from January to December 2013. These subjects were followed until December 2015. Sociodemographic, behavioral, clinical, and laboratory data were obtained from clinical records, pharmacy reports of ART and TB drugs, and in the following databases: (a) Internal Registration CEDAP Laboratory data – CompLab; (b) Logistics Management System Drugs – SICLOM; (c) System Laboratory Tests Control of the National Network of Lymphocyte Count CD4/CD8 and viral load – SISCEL; and (d) Brazilian Information System on Mortality – SIM.

Virological failure was defined as detectable HIV RNA above 1000copies/mL (Abbot molecular, Illinois, USA) in individuals on ART for at least six months. TB diagnosis was assessed by identification of M. tuberculosis in cultures or acid-fast smears in sputum or other tissues, compatible histological findings from tissue biopsies, or compatible clinical features, according to the Brazilian Pneumology Society.15 Information on death was obtained from SIM. The survival time was calculated as the time elapsed between the diagnosis of virological failure and date of death or date of last visit to the Center.

Statistical analyses included χ2 and Fisher's exact tests for comparisons of seroprevalence rates and a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test for comparisons of sociodemographic indicators and laboratory test results between individuals with or without a diagnosis of TB. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V18. Results were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Survival analysis was performed using Cox backward stepwise regression analysis with the variables associated or near association (less than eight years of education, less than 200cells/mm3 of CD4 at failure, CMV retinitis or CNS toxoplasmosis, presence of comorbidities), prediction of death between groups (with or without a diagnosis of TB). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Department of the Bahia's State (SESAB), number 452782.

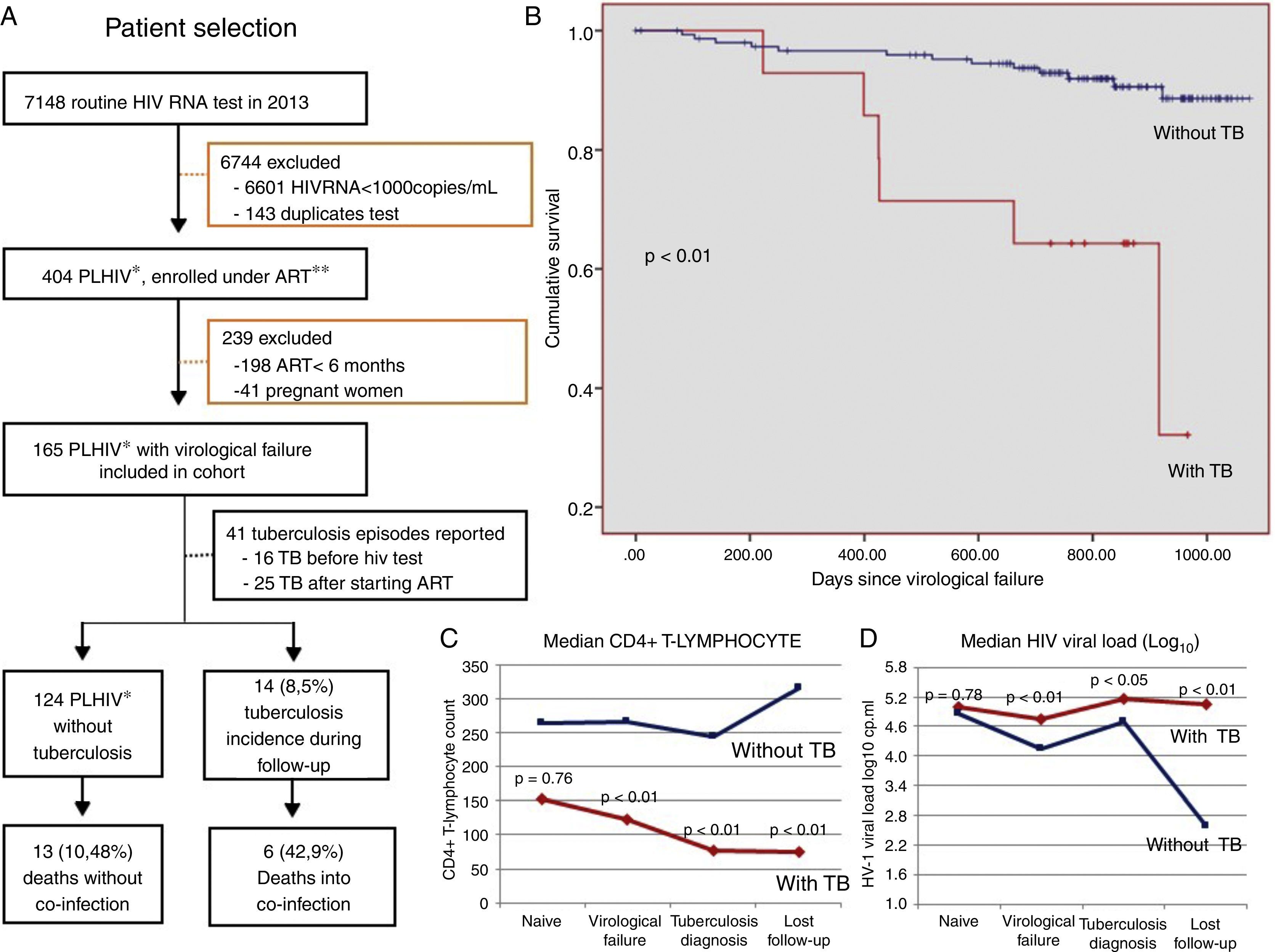

We identified 165 patients with HIV infection with virological failure in 2013 (Fig. 1A). TB incidence was 8.5% (14 cases) within the two years of follow-up (incidence density=4.1 cases in 100 patient-years). Among these 165 patients, 41 (32.7%) had a history of TB infection prior to virological failure. Of these, 16 (9.7%) patients already had active TB at the time of HIV diagnosis and started ART an average of 428.6 days after diagnosis (median 183 days). Seven (4.2%) patients postponed the initiation of ART because of TB diagnosis an average of 1300 days after the diagnosis of HIV (median=1038 days). Ten (18.9%) of these patients developed TB while being treated with ART but before HIV virological failure.

(A) Flow chart for patient selection and follow-up; (B) Kaplan–Meier curves according to tuberculosis (TB) status (Breslow–Day test); (C) median CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and (D) median viral load in HIV-positive adults with (n=14) and without TB (n=151) (Mann–Whitney test), after virological failure of HIV, Salvador, Bahia. *People living with HIV; **ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Of the 165 patients included, 19 (11.5%) died. There were six deaths directly related to TB/HIV co-infection (42.9%), with a mortality rate of 1.7 in 100 patient-years. Poorer survival was observed in patients who developed TB during follow-up and TB related mortality was high (p<0.01) (Fig. 1B).

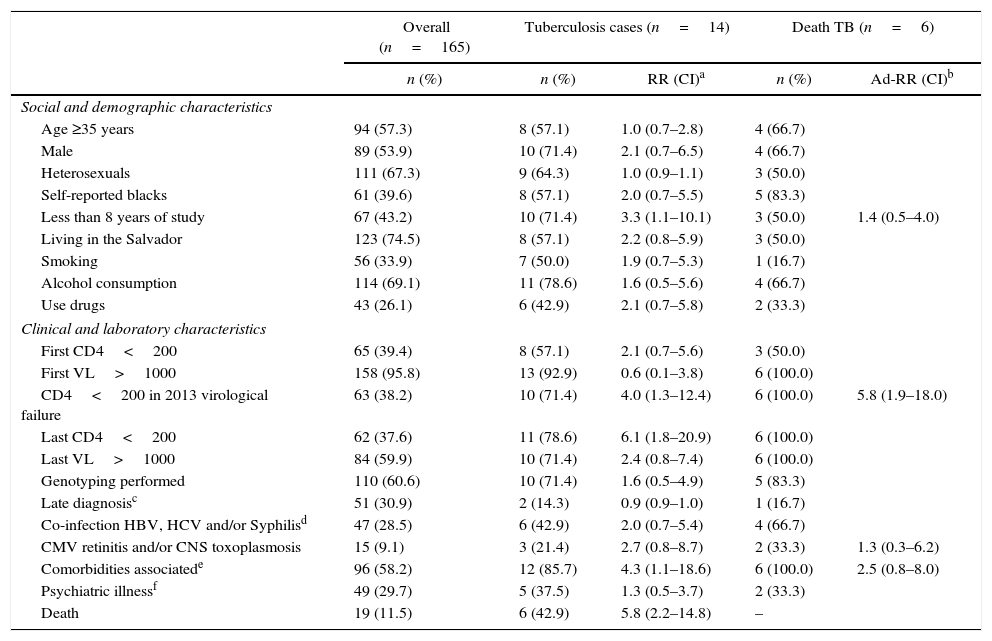

In our cohort TB was more incident in males (71.4%), self-reported blacks (57.1%), heterosexuals (64.3%), and those with less than four years of education (71.4%). The most frequent age group was 30–39 years (35.7%) with a mean age of 36.9 years (range: 18–67 years). Less than eight years of education, CD4 T-cell count below 200cells/mm3, and presence of clinical comorbidities were associated with the incidence of TB in these patients with virological failure (Table 1). The median CD4 count at the moment of virological failure was 123cells/mm3 (±204), lower than that at diagnosis (152.5cells/mm3; p<0.01). In the last follow-up visit, only 14.3% had a viral load of <50 HIV RNA copies/mL. High median viral load and low CD4 count were associated with increased incidence of TB and lower survival (p<0.01) as shown in Fig. 1B, C and D. After multivariate analysis, all variables previously associated in the univariate analysis remained statistically associated with the occurrence of TB. Only CD4 less than 200cells/mm3 remained associated with death (p<0.01) (Table 1).

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of people living with HIV/AIDS diagnosed with virological failure in 2013, State HIV/AIDS Reference Center, according to diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) and death, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

| Overall (n=165) | Tuberculosis cases (n=14) | Death TB (n=6) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | RR (CI)a | n (%) | Ad-RR (CI)b | |

| Social and demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age ≥35 years | 94 (57.3) | 8 (57.1) | 1.0 (0.7–2.8) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Male | 89 (53.9) | 10 (71.4) | 2.1 (0.7–6.5) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Heterosexuals | 111 (67.3) | 9 (64.3) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Self-reported blacks | 61 (39.6) | 8 (57.1) | 2.0 (0.7–5.5) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Less than 8 years of study | 67 (43.2) | 10 (71.4) | 3.3 (1.1–10.1) | 3 (50.0) | 1.4 (0.5–4.0) |

| Living in the Salvador | 123 (74.5) | 8 (57.1) | 2.2 (0.8–5.9) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Smoking | 56 (33.9) | 7 (50.0) | 1.9 (0.7–5.3) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 114 (69.1) | 11 (78.6) | 1.6 (0.5–5.6) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Use drugs | 43 (26.1) | 6 (42.9) | 2.1 (0.7–5.8) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Clinical and laboratory characteristics | |||||

| First CD4<200 | 65 (39.4) | 8 (57.1) | 2.1 (0.7–5.6) | 3 (50.0) | |

| First VL>1000 | 158 (95.8) | 13 (92.9) | 0.6 (0.1–3.8) | 6 (100.0) | |

| CD4<200 in 2013 virological failure | 63 (38.2) | 10 (71.4) | 4.0 (1.3–12.4) | 6 (100.0) | 5.8 (1.9–18.0) |

| Last CD4<200 | 62 (37.6) | 11 (78.6) | 6.1 (1.8–20.9) | 6 (100.0) | |

| Last VL>1000 | 84 (59.9) | 10 (71.4) | 2.4 (0.8–7.4) | 6 (100.0) | |

| Genotyping performed | 110 (60.6) | 10 (71.4) | 1.6 (0.5–4.9) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Late diagnosisc | 51 (30.9) | 2 (14.3) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Co-infection HBV, HCV and/or Syphilisd | 47 (28.5) | 6 (42.9) | 2.0 (0.7–5.4) | 4 (66.7) | |

| CMV retinitis and/or CNS toxoplasmosis | 15 (9.1) | 3 (21.4) | 2.7 (0.8–8.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1.3 (0.3–6.2) |

| Comorbidities associatede | 96 (58.2) | 12 (85.7) | 4.3 (1.1–18.6) | 6 (100.0) | 2.5 (0.8–8.0) |

| Psychiatric illnessf | 49 (29.7) | 5 (37.5) | 1.3 (0.5–3.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Death | 19 (11.5) | 6 (42.9) | 5.8 (2.2–14.8) | – | |

HBV, HCV and/or syphilis co-infection: hepatitis B surface antigen (AgHBs, Abbott Laboratories, Wiesbaden, Germany), hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV, Abbott Laboratories, Wiesbaden, Germany) and syphilis rapid test (immunochromatography-rapid treponemal lateral flow device, ALERE S.A., São Paulo, Brazil) and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL, OMEGA Diagnostics Ltd., Scotland, United Kingdom).

Our study showed that 8.5% (14/165) of patients failing HIV therapy were diagnosed with TB within two years of follow-up. Low level education and low CD4 cell counts at diagnosis of virological failure were risk factors associated with TB and early mortality. Several studies have shown that a low CD4 count is associated with a higher likelihood of virological failure,12,13,16,17 opportunistic infection onset, disease progression, and a higher risk of associated health problems.18,19

The incidence of TB was also significantly associated with virological failure,3,12 but to date, the importance of TB incidence and related mortality have not been observed after virological failure. Early detection of virological failure and adoption of appropriate measures to ensure viral suppression and immune recovery may also reduce the incidence of TB.

This study had some limitations. This retrospective, observational study was limited to one center and the data used in this analysis were from a secondary source, resulting in incomplete data for some patients; however, we conducted additional data searches in the official database of Brazil (SICLOM, SISCEL, SIM) to improve the quality of information obtained from medical records. Our evaluation was limited to patients who had available for review CD4 and HIV viral load testing in 2013. In addition, HIV-1 viral load, considered to be the best predictor of HIV disease progression,20 was the measure used in the present study.

However, published data indicate high early mortality in patients with virological failure and co-infection with TB.13 Therefore, our results could be an underestimation of virological failure and consequently, reduction of detectable cases of TB. Our cohort was not very large; only 165 patients were diagnosed with virological failure for inclusion in the study. On the other hand, the study site was the largest reference center for care of PLWHA in the state of Bahia, and the incidence of TB was high enough to draw relevant conclusions.

In summary, TB is associated with a high mortality rate when it is diagnosed in the context of virological failure. The diagnosis and prophylaxis for TB in high-incidence countries such as Brazil is critical to decrease morbidity and mortality in patients living with HIV.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.