Comparative data on hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir, commonly used agents in the treatment of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19), are still limited. In this study, it was aimed to compare treatment outcomes in healthcare workers with COVID-19 who were prospectively followed by the occupational health and safety unit.

MethodsA total of 237 healthcare-workers, diagnosed as mild or moderate COVID-19 between March 11, 2020 and January 1, 2021, were given hydroxychloroquine (n = 114) or favipiravir (n = 123). Clinical and laboratory findings were evaluated.

ResultsThe mean age of the patients was 33.4±11.5 years. The mean time to negative PCR was found to be significantly shorter in patients receiving favipiravir compared to the hydroxychloroquine group (10.9 vs. 13.9 days; p < 0.001). The rate of hospitalization in the hydroxychloroquine group was significantly higher than favipiravir group (15.8% vs. 3.3%). In terms of side effects; the frequency of diarrhea in patients receiving hydroxychloroquine was significantly higher than that in the favipiravir group (31.6% vs. 6.5%; p < 0.001).

ConclusionsFavipiravir and hydroxychloroquine were similar in terms of improvement of clinical symptoms of healthcare workers with mild or moderate COVID-19 infection, but favipiravir was significantly more effective in reducing viral load and hospitalization rates. Furthermore, favipiravir caused significantly less side-effects than hydroxychloroquine.

Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) has caused a pandemic that spread rapidly all over the world since December 2019. This pandemic led to several million cases and deaths within approximately one and a half year.1,2

Many agents are used for treating COVID-19, for which no definitive cure has yet been found. In COVID-19 cases, the characteristics of the patient, clinical condition, laboratory and radiological findings determine the treatment management.2–4 Although the treatment of COVID-19 generally includes a symptomatic approach, depending on severity of the infection, agents that reduce viral load or stimulate the immune response against infection have been tried and/or used. Among the most commonly used agents were hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir.3,5

Hydroxychloroquine is an agent that has been used for a long time in the treatment of malaria and some autoimmune diseases. Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), the agent of COVID-19, from entering the cell by glicolizing spike proteins on the virus surface and angiotensin converting enzyme-2 receptors, used as viral receptor. Hydroxychloroquine has also been reported to reduce the inflammatory response and cytokine storm in vitro, to reduce proinflammatory cytokine production, to activate anti-SARS-CoV-2 T cells, to inhibit virus-cell junction by increasing endosomal pH, and to inhibit pH-dependent steps of viral replication.2,3 Due to these mechanisms of action, it has been used in the treatment of COVID-19 during the pandemic process. However, its use has been restricted, especially when side-effects such as cardiac conduction disturbances became frequently reported.2–4,6

It has been suggested that the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRp) enzyme found in SARS-CoV-2 is 10-fold more active than the RDRp enzymes from other known viruses.7 Favipiravir, a guanosine analog that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, had been used in severe influenza cases and influenza outbreaks in Japan.7,8 With this mechanism of action, it begun to be widely used in COVID-19 patients during the pandemic process aiming at reducing viral replication. It has been more commonly used in severe COVID-19 cases or in those that require hospitalization.8,9

The efficacy and side effects of the agents that have been tried or used in the treatment of COVID-19 have not been fully elucidated. Comparative data on hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir, which are commonly used agents in the treatment of this infection, are still limited. In addition, patients’ knowledge and awareness about the infection can interfere in the evaluation of treatment clinical response and compliance.2–4 However, there is not enough research about the effect of sociodemographic differences of COVID-19 patients on treatment outcomes. For these reasons, in this study, it was aimed to compare the effects of hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir treatment on clinical and laboratory findings, and to evaluate the differences in treatment outcomes in healthcare workers with COVID-19 who were prospectively followed by the occupational health and safety unit.

Material and methodsThis study was approved by the local ethics committee (2021/04-640) with the permission of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Turkey, and was planned retrospectively.

Patients and testsA total of 237 healthcare-workers diagnosed with mild or moderate COVID-19 between March 11, 2020 and January 1, 2021 at the clinics of Chest Diseases or Infectious Diseases of our hospital and followed up by the occupational health and safety unit, to whom hydroxychloroquine (n = 114) or favipiravir (n = 123) were given were included in the study. The number of healthcare workers to whom neither drug was given was too small to allow for any comparison.

Patients whose diagnosis of COVID-19 was not confirmed by SARS-CoV-2 PCR and those who did not receive hydroxychloroquine or favipiravir were excluded from the study. In addition, patients who were given additional antiviral treatment were not included.

Patients diagnosed with mild or moderate COVID-19 infection were given high dose favipiravir 1600 mg bid per oral on the 1st day, and 600 mg bid per oral on days 2-5 or hydroxychloroquine 400 mg bid per oral on the 1st day, and 200 mg bid per oral on days 2-5.

Follow upAll healthcare professionals diagnosed as COVID-19 were prospectively followed up and recorded by the occupational health and safety unit. Symptoms, drug use, and initial laboratory findings were evaluated. The duration of fever, respiratory distress and drug side-effects were recorded every two days. SARS-CoV-2 PCR negativity between 7-10 days of follow-up were evaluated in the two treatment groups. Those who were still PCR positive were called to the hospital for a second test between 14-20 days and every seven days after the 21st day for another PCR test. Healthcare workers whose SARS-CoV-2 PCR turned out negative were invited to resume working in the hospital (Tables 3 and 4).

The decision for outpatient follow-up and inpatient follow-up was made by chest diseases specialists, and the clinical follow-up of inpatients was made by infectious diseases specialists.

Hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir were given according to the guidelines published by the Turkish Ministry of Health. Hydroxychloroquine was used for healthcare professionals who had COVID-19 infection in the March-July period, and favipiravir for healthcare professionals who had COVID-19 infection in the July-January period. Paracetamol was prescribed to all healthcare professionals as a symptomatic treatment.

Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses in this study were performed using SPSS 25.0 software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive data are given as numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were compared between groups using Pearson's chi square test or Fisher's exact test when appropriate. Normal distribution of continuous variables were assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. Continuous variables were compared between groups using Student's t-test, and the comparison of mean values among multiple groups by analysis of variance. The results were evaluated within the 95% confidence intervals, and p < 0.05 values were considered significant. Bonferroni correction was made where appropriate.

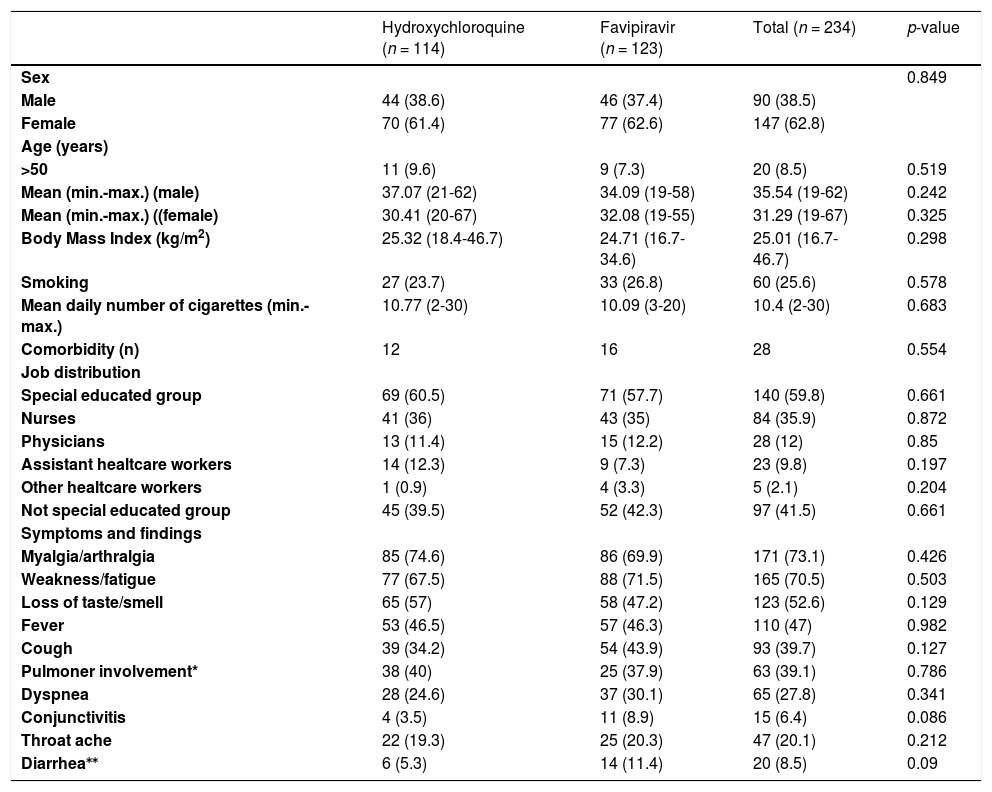

ResultsDemographic informationPatients’ mean age was 33.4±11.5 years, 90 (38.6%) patients were male, 84 (35.9%) were nurses, and 28 (12%) physicians (Table 1).

Baseline patient characteristics according to treatment groups.

| Hydroxychloroquine (n = 114) | Favipiravir (n = 123) | Total (n = 234) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.849 | |||

| Male | 44 (38.6) | 46 (37.4) | 90 (38.5) | |

| Female | 70 (61.4) | 77 (62.6) | 147 (62.8) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| >50 | 11 (9.6) | 9 (7.3) | 20 (8.5) | 0.519 |

| Mean (min.-max.) (male) | 37.07 (21-62) | 34.09 (19-58) | 35.54 (19-62) | 0.242 |

| Mean (min.-max.) ((female) | 30.41 (20-67) | 32.08 (19-55) | 31.29 (19-67) | 0.325 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.32 (18.4-46.7) | 24.71 (16.7-34.6) | 25.01 (16.7-46.7) | 0.298 |

| Smoking | 27 (23.7) | 33 (26.8) | 60 (25.6) | 0.578 |

| Mean daily number of cigarettes (min.-max.) | 10.77 (2-30) | 10.09 (3-20) | 10.4 (2-30) | 0.683 |

| Comorbidity (n) | 12 | 16 | 28 | 0.554 |

| Job distribution | ||||

| Special educated group | 69 (60.5) | 71 (57.7) | 140 (59.8) | 0.661 |

| Nurses | 41 (36) | 43 (35) | 84 (35.9) | 0.872 |

| Physicians | 13 (11.4) | 15 (12.2) | 28 (12) | 0.85 |

| Assistant healtcare workers | 14 (12.3) | 9 (7.3) | 23 (9.8) | 0.197 |

| Other healtcare workers | 1 (0.9) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (2.1) | 0.204 |

| Not special educated group | 45 (39.5) | 52 (42.3) | 97 (41.5) | 0.661 |

| Symptoms and findings | ||||

| Myalgia/arthralgia | 85 (74.6) | 86 (69.9) | 171 (73.1) | 0.426 |

| Weakness/fatigue | 77 (67.5) | 88 (71.5) | 165 (70.5) | 0.503 |

| Loss of taste/smell | 65 (57) | 58 (47.2) | 123 (52.6) | 0.129 |

| Fever | 53 (46.5) | 57 (46.3) | 110 (47) | 0.982 |

| Cough | 39 (34.2) | 54 (43.9) | 93 (39.7) | 0.127 |

| Pulmoner involvement* | 38 (40) | 25 (37.9) | 63 (39.1) | 0.786 |

| Dyspnea | 28 (24.6) | 37 (30.1) | 65 (27.8) | 0.341 |

| Conjunctivitis | 4 (3.5) | 11 (8.9) | 15 (6.4) | 0.086 |

| Throat ache | 22 (19.3) | 25 (20.3) | 47 (20.1) | 0.212 |

| Diarrhea⁎⁎ | 6 (5.3) | 14 (11.4) | 20 (8.5) | 0.09 |

The most common symptoms were muscle/joint pain (73.1%), weakness/fatigue (70.5%), loss of taste/smell (52.6%), fever (47%), and cough (39.7%). Hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir groups were found to be similar in terms of symptom distribution (p > 0.05 for each) (Table 1).

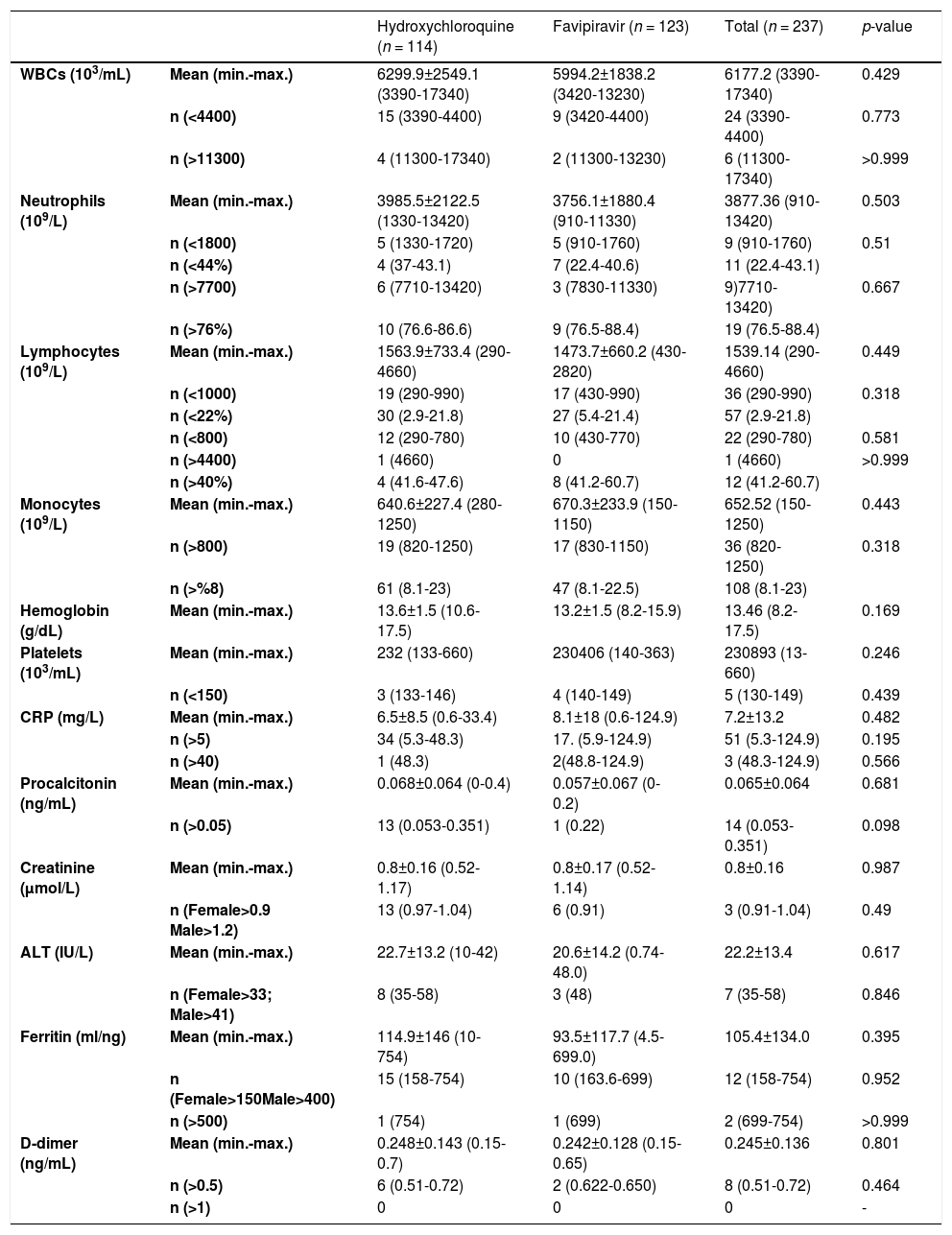

Mean laboratory values at the time of diagnosis and ratios of leukopenia, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, neutropenia, lymphocytosis, lymphopenia, monocytosis, thrombocytopenia and abnormal biochemical parameters (p > 0.05 for each) were also similar in the two treatment groups (Table 2).

Baseline laboraory results according to treatment groups.

WBC: White blood cell, CRP: C-reactive protein, ALT: Alanine transferase.

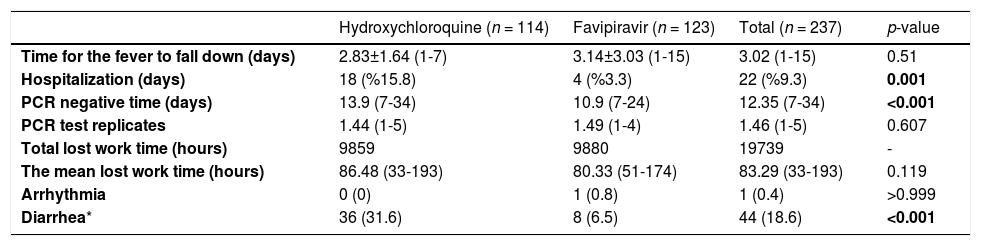

The mean time to negative for SARS-CoV-2 PCR in patients receiving favipiravir was found to be significantly lower than in those receiving hydroxychloroquine (10.9 vs. 13.9 days; p < 0.001). Hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir groups had similar mean duration of fever (p = 0.51) and mean lost work time (p = 0.119) (Table 3).

Outcome variables according to treatment group.

| Hydroxychloroquine (n = 114) | Favipiravir (n = 123) | Total (n = 237) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time for the fever to fall down (days) | 2.83±1.64 (1-7) | 3.14±3.03 (1-15) | 3.02 (1-15) | 0.51 |

| Hospitalization (days) | 18 (%15.8) | 4 (%3.3) | 22 (%9.3) | 0.001 |

| PCR negative time (days) | 13.9 (7-34) | 10.9 (7-24) | 12.35 (7-34) | <0.001 |

| PCR test replicates | 1.44 (1-5) | 1.49 (1-4) | 1.46 (1-5) | 0.607 |

| Total lost work time (hours) | 9859 | 9880 | 19739 | - |

| The mean lost work time (hours) | 86.48 (33-193) | 80.33 (51-174) | 83.29 (33-193) | 0.119 |

| Arrhythmia | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | >0.999 |

| Diarrhea* | 36 (31.6) | 8 (6.5) | 44 (18.6) | <0.001 |

Hospitalization rate (3.3%) in those who received favipiravir treatment was found to be significantly lower than among those who received hydroxychloroquine (15.8%) (p = 0.001) (Table 3).

In terms of side effects; the frequency of diarrhea in patients receiving hydroxychloroquine was significantly higher than that of the favipiravir group (31.6% vs. 6.5%; p < 0.001). In addition, arrhythmia developed in a patient who received favipiravir (Table 3).

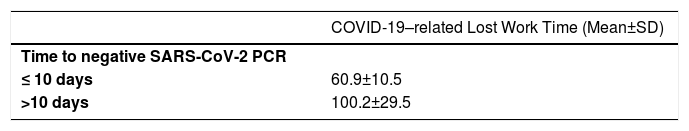

The mean COVID-19–related lost work time was found to be significantly lower in those with a SARS-CoV-2 PCR negative time less than 10 days compared to those with a SARS-CoV-2 PCR negative time longer than 10 days (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

DiscussionIn the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic process, there was some debate about the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine, which was widely used in treatment, and it was thought not to be reliable enough in terms of side-effects, thus limiting its use. Favipiravir, which is one of the agents that continues to be investigated, has started to be used more widely.2–4,6 However, there are insufficient comparative data on the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir in COVID-19 cases. In this study, the efficacy and safety of favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine were examined.

The most common symptoms were muscle/joint pain (73.1%), weakness/fatigue (70.5%), loss of taste/smell (52.6%), fever (47%), and cough (39.7%). Therefore, considering that muscle-joint pain and weakness in mild or moderate COVID-19 infection, fever, and cough in severe COVID-19 infection are at the forefront, it shows that the cases included in the study were mild or moderate and the common COVID-19 findings are generally overlapped.1,3

In the present study, the hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir groups were found to be similar in terms of baseline symptoms and mean laboratory values, such as leukopenia, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, neutropenia, lymphocytosis, lymphopenia, monocytosis, thrombocytopenia and abnormal biochemical parameter ratios. These findings show that patient characteristics of both mild or moderate COVID-19 treatment groups included in the study were similar.

In the present study, baseline leukopenia was found in 10.1% and lymphopenia in 15.2% of the participants. Considering that healthcare workers are likely to be exposed to a higher viral load, it seems warranted to follow those healthcare patients with leukopenia and lymphopenia more closely.

Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to be effective in COVID-19 cases.8 However, in a meta-analysis, it was reported that the use of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 cases did not affect mortality and development of respiratory failure.6 In two meta-analyses, it was concluded that there was insufficient evidence about the effects of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 cases.10,11 It has been reported that favipiravir is more effective in terms of viral clearance in COVID-19 cases compared to some other antivirals.8,12 In an experimental study, it was shown that high-dose favipiravir had antiviral activity, but hydroxychloroquine had no antiviral effect.13 In another study, favipiravir had no significant effect in terms of viral clearance in COVID-19 cases.14 However, in a meta-analysis, it was reported that favipiravir shortened the length of hospital stay and decreased the mortality rate in COVID-19 cases.15 In another meta-analysis, it was determined that favipiravir shortened the time to negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR by an average of five days compared to other agents.16 In the present study, it was observed that the mean time to negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR was three days shorter in the favipiravir group compared to the hydroxychloroquine group, and the difference was statistically significant. These findings suggest that favipiravir is more effective than hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 in terms of reducing viral load. Therefore, favipiravir may be more effective in decreasing transmission, slowing the social spread and reducing the number of new cases.

In a meta-analysis, it was stated that the use of hydroxychloroquine did not affect the duration of fever reduction in COVID-19 cases.6 In the present study, hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir groups were found to be similar in terms of mean duration of fever in patients with fever. These findings show that favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine were not different in terms of improvement of clinical symptoms.

There are limited data in terms of clinical deterioration among favipiravir and other treatment options. However, it has been stated that favipiravir has greater efficacy in reducing mortality and hospital stay compared to other treatment options, but these conclusions are not yet definitive.15 In a large meta-analysis, the rates of clinical and radiological deterioration, need for oxygen support and for non-invasive ventilation were found to be similar between patients who were given favipiravir and other treatment options.16 In the present study, the rate of hospitalization was found to be significantly higher in those receiving hydroxychloroquine compared to those received favipiravir (15.8% vs. 3.3%). This finding shows that favipiravir significantly prevented aggravation of mild or moderate COVID-19 clinical picture. This supports that favipiravir is more effective in the course and prognosis of COVID-19.

The agents used in the treatment of COVID-19 have different side-effects. Although in one report favipiravir did not show any significant side-effect,8 systematic reviews suggest that it may cause increased serum transaminases and uric acid levels. Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to cause electrolyte and cardiac rhythm disturbances and retinopathy in long-term use.2,17 In a comparative study, it was reported that liver enzymes increased in COVID-19 patients receiving favipiravir, but no change was observed in the hydroxychloroquine group.18 In another study, a significant prolongation in the QTc interval was found in electrocardiography in patients who received hydroxychloroquine and no change was observed in patients receiving favipiravir.19 Likewise, a meta-analysis showed that the risk of cardiac conduction disturbance increased after the use of hydroxychloroquine.6 In the present study, it was observed that an arrhythmia developed in a patient who received favipiravir, but no cardiac side-effects were found in those taking hydroxychloroquine. The low mean age of the patients may be the reason why cardiac side-effects were observed less frequently. Nevertheless, the possible liver and cardiac side-effects of hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir should be investigated extensively and patients should be closely monitored for these effects. It has been stated that favipiravir may cause diarrhea at a rate of approximately 5%.7 In the present study, the rate of developing diarrhea in patients who received hydroxychloroquine was found to be significantly higher than that of the favipiravir group (31.6% vs. 6.5%). These findings suggests that favipiravir is safer in terms of side-effects in the younger age group.

The first outcome assessed between 7-10 days of follow-up was SARS-CoV-2 PCR negativity. Those still positive for SARS-CoV-2 PCR were tested for the second time between the 14th and 20th days and every seven days after the 21st day. Healthcare professionals whose SARS-CoV-2 PCR turned out negative were invited to resume working in the hospital (Table 4). The mean COVID-19–related lost work time was similar in patients who received hydroxychloroquine or favipiravir, but it was significantly lower in those whose SARS-CoV-2 PCR turned out negative in less than 10 days after initiation of treatment. This conclusion, also seems to be compatible with previous data indicating that healthcare workers can start working again at the end of seven days, which is the known time of disappearance of transmission after getting COVID-19. This finding indicates that if SARS-CoV-2 PCR negativity is expected, lost work time can be reduced.

The present study had some limitations. In order to make a direct comparison of hydroxychloroquine and favipiravir and to avoid bias, patients who received these agents in combination with other drugs were excluded from the study. In addition, the very long-term efficacy and side-effects of these agents could not be analyzed due to the short-term planning of the study. There was no follow up changes in the long-term liver enzymes and uric acid levels of the patients.

ConclusionsThe findings of the present study show that favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine were similar in terms of improvement of clinical symptoms in healthcare workers with mild or moderate COVID-19 infection, but that favipiravir was significantly more effective in reducing viral load and decreasing hospitalization rates. In addition, the findings have shown those whose SARS-CoV-2 PCR turned out negative in less than 10 days after initiation of treatment had a lost work time significantly lower than those who became PCR negative after 10 days. Favipiravir caused significantly less side-effects than hydroxychloroquine. Therefore, favipiravir is thought to be a useful agent in the treatment of mild or moderate COVID-19 infection. However, large-scale studies should be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of favipiravir to treat COVID-19 infection.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.