The heterogeneity in detection rates of Human immunodeficiency virus, (HIV), Human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV) and Hepatitis B and C infections among pregnant women and the continuous exposure to risk factors limits the adoption of preventive and control actions.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the HIV, HTLV, Hepatitis B and C seroprevalence rates, and associated risk factors in parturient women in Salvador, Brazil.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study in 2099 parturient women attended in two public maternity hospitals in Salvador, Brazil. One blood sample was drawn for serological screening and socio-demographic, obstetric and clinical data were collected.

ResultsHIV seroprevalence rate was 1.5% (of which 0.6% were new cases); seroprevalence rates for HTLV, HBV, and HCV were 0.4%, 0.4%, and 0.1%, respectively. Univariate analysis showed a significant association between socio-demographic and behavioral factors with retroviral infections, while viral hepatitis was mainly associated with parenteral exposure. In a multivariate analysis, multiple sexual partners (OR 3.3; 95% CI: 1.1–9.2), history of sexual/domestic violence (OR 2.8; 95% CI: 1.1–6.9), syphilis co-infection (OR 2.6; 95% CI: 1.0–6.9), use of alcohol or drugs (OR 2.5; 95% CI: 1.2–5.5), and low schooling level (OR 2.3; 95% CI: 1.1–4.9) were independent risk factors for HIV infection. History of stillbirth and low birth weight infants was significantly associated with HTLV positive status, showing a negative impact on gestation.

ConclusionsThe seroprevalence rates for HIV, HCV, HBV, and HTLV were similar to that found in previous studies in other Brazilian regions. The high individual, socioeconomic, and social vulnerability detected in seropositive parturient women indicates the need to improve coverage and effectiveveness of STDs control with prevention, detection and monitoring strategies, focusing in pregnant women exposed to high biopsychosocial risk.

Serological screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV 1/2), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in pregnant women is essential for monitoring vertical transmission (VT) of these infections. Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of such viral diseases is a serious public health problem associated with important morbidity and mortality.

Globally, the HIV MCT rate was 10% in 2016, with four countries certified by the World Health Organization (WHO) for eliminating HIV MTCT: Armenia, Belarus, Cuba, and Thailand. New HIV infections in children decreased in the 2010–2015 period, but there are regions with transmission rates above the world average, such as the countries of the Middle East, Asia and the Pacific, North Africa, West Africa and Central Africa.1 In Latin America and the Caribbean, the trend in this rate decreased from 17% in 2010 to 12% in 2017, representing the prevention of nearly 30,800 HIV infections in children.2

In Brazil, 108,134 cases of pregnant women with HIV were reported from 2007 to June 2017, of which 16.8% gave birth in the Northeastern (NE) region, according to the Notifiable Diseases Information System. In that period, the detection rate of HIV-infected pregnant women increased from 1.2 to 2 cases per 1000 live births (LB) in the NE region, but remained lower than the national rate (2.7 cases per 1000 LB).3

The global prevalence of HBsAg in the general population was estimated as 4–9%, and in children under five years of age it was estimated as 3–4% in Africa, 1.5% in South-East Asia, 0.5% Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific, and as 0.1% in Europe and America. In low-income countries, the prevalence ranges from 1 to 9%, while in lower-middle income countries it is of 2%.4

In Brazil, there were 23,563 (11.1%) cases of HBV infection in pregnant women reported in the 1999–2015 period, an incidence of 0.4 cases per 1000 LB. The highest number of cases were reported in the southern (33.7%) and southeastern (26.1%) regions.5

In the same period, the rate of HCV infection showed an increasing trend in all Brazilian regions, with 64.1% of cases being detected in the Southeastern, 24.5% in the South, and 5.5% in the NE regions.5 Additionally, the prevalence of pediatric infection varied from 0.05%-0.36% in the United States and Europe, while in some developing countries it ranged from 1.8%-5.8%. The highest prevalence occurred in Egypt, sub-Saharan Africa, the Amazon basin and Mongolia.6

Prevalence rates of maternal HTLV-1 infection vary from 0.05% in Europe, 1% in America (excluding Brazil), 2% in Africa, to 4.4% in Asia. The city of Salvador, capital of the Brazilian Bahia state, has the highest seroprevalence rate (1.8%) in the general population among all Brazilian state capitals, although it is lower (0.84%) in pregnant women.7

There is a body of comprehensive information on seroprevalence rates and epidemiological data regarding HIV-1. However, data on transmission of other potentially chronic viral infections (HTLV, HBV, and HCV) in Brazil, especially on VT, are scarce. This study aimed to evaluate the seroprevalence rates for these viral infections and the risk factors associated with their occurrence in parturient women in Salvador, Bahia.

MethodsStudy populationThe study population consisted of 2099 parturient women attended at two public maternity hospitals in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil: Maternidade Referência Professor José Maria Magalhães Neto (MRPJMMN) and Maternidade Climério de Oliveira (MCO). The two institutions are the leading public maternity hospitals in the city of Salvador, located in the NE region of Brazil. According to the Live Births Information System, in 2014, 45,992 live births were recorded in Salvador, with an estimated 3833 births per month.

Study design and samplingThis is a cross-sectional study with data collection from April 2016 to June 2017. The sample size was calculated with an estimated mean prevalence of 0.7% of infections in pregnant women in Salvador, considering 80% power of detection of differences, 95% confidence interval, and an excess of 10% to cater for any losses.

A consecutive sample of parturient women who sought MRPJMMN and MCO maternities at birth and who agreed to participate in this research were included in the study, after signing the informed consent form. Mothers who were unable to provide answers were excluded.

One blood sample was collected for additional serology and women were asked to answer a questionnaire about socio-demographic factors (age, marital status, schooling, occupation, ethnicity, and data on risk behaviors and vulnerability conditions), obstetric factors (obstetric history, number of antenatal visits, hepatitis B vaccine), clinical/epidemiological factors (presence of associated infections, time of diagnosis of infection, partner serological status) delivery/childbirth/puerperal factors (premature rupture of membranes, type of delivery, invasive methods, weight, gestational age, and breastfeeding).

Serological testsWe used routine admission laboratory tests performed in parturient women of the two maternities. Rapid tests were employed at the MRPJMMN (Abon Biopharm, Hangzhou, China) and the MCO (Alere Determine™ HIV1/2, Ireland) to detect HIV antibodies. For the qualitative identification of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg), VIKIA® test (BioMérieux, Brazil) was used at both maternities. HCV screening was performed at the MCO using the Alere™ HCV test (Standard Diagnostic INC, Republic of Korea).

These two maternities do not perform routine HTLV screening on admission. HTLV and HCV serological screening were performed in the Infectious Diseases Research Laboratory (Laboratório de Pesquisa em Infectologia, LAPI). HTLV antibodies were detected using ELISA Recombinant v4.0 (Wiener lab., Argentina), and 3rd generation ELISA (Wiener lab., Argentina) was used for HCV. Positive results of HTLV infections were confirmed by Western blot (WB) or PCR, and by RNA PCR test for HCV.

Statistical analysisThe Statistical Package Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 22, was used for statistical analysis. The significant level was set for values of s<0.05. Prevalence rates were calculated for each viral infection studied. The associations between categorical variables were assessed using univariate analysis (Pearson's Chi-square test) and the risk was expressed as Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney, as indicated. A stepwise multiple logistic regression model was constructed, with inclusion of variables with an estimated level of significance in univariate analysis lower than 0.2, to evaluate the strength of association of the different factors with HIV seropositivity. Variables with significance level lower than 0.05 were maintained in the final model. The results are expressed as adjusted OR and 95% CI.

Ethics CommitteeThe Institutional Research Ethics Committee of both institutions approved the study (report N° 2.385.099 of September 12, 2015).

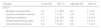

ResultsA total of 2099 parturient women, equivalent to 19.1% of the 10,965 deliveries that took place at the MCO and MRPJMMN maternities during the collection period, were included in the study. Most (71.2%) lived in Salvador, had a mean age of 27.3±6.9 years (range from 14 to 46 years), 6% of adolescents (<18 years). There were no significant differences between the characteristics of the participants of the two maternities. The socio-demographic, obstetric and clinical profiles of the study sample are shown in Table 1. The participants reported a mean of 2.2 (SD=1.5) previous pregnancies.

Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics among parturient women at maternity hospitals MCO and MRPJMMN, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 2016–2017.

| Variables | Total N=2099 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14–19 | 337 (16.1) |

| 20–29 | 1020 (48.6) | |

| 30–39 | 633 (1.6) | |

| >40 | 79 (3.8) | |

| Education (years) | <8 | 569 (27.1) |

| >8 | 1528 (72.7) | |

| Employment | Yes | 727 (34.6) |

| Race (self-reported) | Mixed | 1041 (50.3) |

| Black | 847 (40.9) | |

| Other (White, Asian, Indigenous) | 183 (8.8) | |

| Risk behavior and vulnerability conditions | ||

| Own house | 1188 (57.0) | |

| Overcrowdinga | 297 (4.1) | |

| Low family incomeb | 977 (46.5) | |

| Alcohol and/or illicit drug user | 350 (16.8) | |

| Previous Incarceration | 90 (4.3) | |

| Sexual and/or domestic violence | 140 (6.7) | |

| Multiple sexual partner in pregnancy | 80 (4) | |

| Other vulnerable conditionsc | 100 (5.0) | |

| Obstetric history | ||

| Number of gestations | 1 | 851 (40.5) |

| 2–3 | 923 (44.0) | |

| >4 | 323 (15.5) | |

| Previous miscarriage | 485 (23.2) | |

| Previous stillbirth | 98 (4.7) | |

| Number of antenatal visits | None | 56 (2.9) |

| 1–5 | 582 (30.0) | |

| >6 | 1300 (67.1) | |

| Ignored | 161 (7.7) | |

| First antenatal visit (trimester) | First | 1354 (66.7) |

| Second | 559 (27.5) | |

| Third | 117 (5.8) | |

| Syphilis co-infection | 98 (4.7) | |

| Exposure sexual | Unprotected sexual practices | 1572 (74.9) |

| Partner with history of STD | 16 (0.8) | |

| Parenteral | Sharing object of personal use | 585 (28.3) |

| Tattoo, piercing, dental treatment | 796 (38.0) | |

| Blood transfusion | 74 (3.6) | |

| Accidental exposure to blood | 28 (1.4) | |

| Type of delivery | Vaginal | 1183 (56.4) |

| Cesarean | 906 (43.3) | |

| Weight of the newborn | >2500g | 1745 (83.1) |

| <2500g | 352 (16.8) | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | >37 | 1762 (83.9) |

| <37 | 334 (15.9) | |

Table 2 shows the seroprevalence rates of the studied viral infections in the two maternity hospitals. Ten samples were reactive for HTLV antibodies, with nine confirmed by WB (0.4%; 95% CI: 0.2–0.7), while one patient had two negative HTLV serological test results in another laboratory. One HTLV-positive patient was co-infected by HIV and syphilis. Concerning HBV infection, reactive HBsAg test was detected in eight women (0.4%; 95% CI: 0.2–0.7). Nine parturient women were positive for HCV serology; of these, three tested negative in a second sample, and three had no confirmatory test. Of the remaining three, two had a positive HCV PCR and one had a negative PCR result. Hence, HCV seropositivity was of 6/2099 (0.3%; 95% CI: 0.1–0.6) taking into account only the reactive ELISA, and of 0.1% (95% CI: 0.03–0.4) with HCV RNA PCR as confirmatory test.

Seroprevalence of HIV, HTLV, and Hepatitis B/C infection, moment of diagnosis and residence of parturient women at maternity hospital MCO and MRPJMMN, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. 2016–2017.

| N=2099 | HIVb | HTLV | HBV | HCV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Test | ||||||||

| Elisa+ | 33 | 1.5 | 10 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.3 |

| Confirmatorya | 33 | 1.5 | 9 | 0.4 | 8 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Total n, % (IC 95%) | 33 | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 9 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 8 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 2 | 0.1 (0.03–0.4) |

| Moment of diagnosis | ||||||||

| Before antenatal care | 19 | 57.6 | 2 | 22.2 | 5 | 62.5 | 1 | 50.0 |

| During antenatal care | 11 | 33.3 | 5 | 55.5 | 2 | 25.0 | 1 | 50.0 |

| During childbirth | 3 | 9.01 | 2 | 22.2 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Home municipality | ||||||||

| Salvador | 23 | 69.9 | 6 | 66.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 2 | 100 |

| Other | 10 | 30.3 | 3 | 33.3 | 4 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 |

The highest seroprevalence observed was for HIV infection (33/2099), with a prevalence of 1.5% (95% CI 1.1–2.1). Out of these cases, 0.9% was diagnosed before the current pregnancy, while 0.6% was diagnosed during the collection period. No significant difference was found when comparing the characteristics of women with a previous diagnosis and women classified as newly diagnosed cases.

Univariate analyses showed a significant association between HIV or HTLV infection with deprivation of liberty, low family income, history of violence, four or more pregnancies, and lack of antenatal care (Table 3). HIV-infected women had a high rate (18.2%) of active syphilis infection. Mean age, history of stillbirth, and low birth weight were significantly different between HTLV-positive and negative parturient women.

Univariate analysis of socio-demographic, obstetric and clinical factors associated with retroviral (HIV–HTLV) infections among parturient women in maternity hospitals MCO and MRPJMMN. Salvador – Bahia, Brazil 2016–2017.

| Variables | HIV (+)n (%) | HIV (−)n (%) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | HTLV (+)n (%) | HTLV (−)n (%) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean SD. 95% CI) | 29.1 | 27.3 | 0.1 | – | 34.3 | 27.2 | 0.04 | – | |

| Fixed partnership | No | 12 (36.4) | 501(24.3) | 0.1 | 1.8 (0.9–3.7) | 2 (20.0) | 511 (24.5) | 0.7 | 0.7 (0.2–3.6) |

| Yes | 21 (63.6) | 1562(75.7) | 0.1 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 8 (80.0) | 1575 (75.5) | 0.7 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | |

| Education in years | <8 | 18 (54.5) | 551 (26.7) | ≤ 0.001 | 3.3(1.7–6.6) | 4 (40.0) | 565(27.1) | 0.3 | 1.8 (0.5–6.4) |

| Race | Non-White | 27 (81.8) | 1858 (91.3) | 0.1 | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 10 (100.0) | 1860 (91.1) | 0.3 | 1.0 (0.1–0.11) |

| White | 3 (9.1) | 141(6.9) | 0.6 | 1.3 (0.4–4.4) | 0 | 143 (7.0) | 0.4 | – | |

| Alcohol and/or drugs users | 14 (42.4) | 336 (16.4) | ≤ 0.001 | 3.7 (1.8–7.6) | 3 (30.0) | 343(16.7) | 0.3 | 2.1 (0.6–8.3) | |

| Deprived of liberty | 4(12.1) | 86 (4.2) | 0.03 | 3.1(1.1–9.1) | 2(20.0) | 87 (4.2) | 0.01 | 5.6 (1.2–27.0) | |

| Multiple sexual partners | 5(15.2) | 79 (3.9) | ≤ 0.001 | 4.4 (1.7–12.0) | 0 | 84 (4.1) | 0.6 | – | |

| Low family income | 21 (77.8) | 956 (52.3) | 0.01 | 3.2 (1.2–7.9) | 8 (80.0) | 969 (52.5) | 0.01 | 3.6 (0.7–17.0) | |

| Sexual and/or domestic violence | 7 (22.6) | 133 (6.6) | ≤ 0.001 | 4.1 (1.7–9.7) | 4 (40.0) | 135 (6.7) | ≤0.01 | 9.3 (2.5–33.3) | |

| Overcrowding | 8 (24.2) | 236 (11.4) | 0.02 | 2.4 (1.1–5.5) | 2 (20.0) | 242 (11.6) | 0.4 | 1.9 (0.4–9.0) | |

| Number of gestations | 1 | 6(18.2) | 845 (40.9) | 0.01 | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 1(10.0) | 850(40.7) | 0.04 | 0.2 (0.02–1.2) |

| >4 | 11 (33.3) | 314 (15.2) | 0.004 | 2.7 (1.3–5.8) | 5 (50.0) | 320(15.3) | 0.002 | 5.5 (1.5–19.2) | |

| Number of prenatal visits | None | 3 (9.7) | 53 (2.8) | 0.02 | 3.8(1.1–12.7) | 1 (14.3) | 53(2.8) | 0.02 | 5.8 (0.6–49.4) |

| <6 | 16 (51.6) | 622 (32.6) | 0.03 | 2.2 (1.1–4.5) | 4 (57.1) | 627(32.8) | 0.2 | 2.7 (0.5–12.2) | |

| First antenatal visit during the third trimester | 4 (13.3) | 113 (5.7) | 0.1 | 2.6 (0.9–7.5) | 0 | 117 (5.8) | 0.5 | – | |

| Stillbirth | 3 (9.1) | 95 (4.6) | 0.2 | 2.1 (0.6–6.9) | 3(30.0) | 95 (4.6) | ≤ 0.001 | 8.8(2.2–34.0) | |

| Miscarriage | 10 (30.3) | 475 (23.1) | 0.3 | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) | 2 (25.0) | 473 (23.0) | 0.2 | 2.2 (0.6–7.9) | |

| Syphilis | 6 (18.2) | 92 (4.5) | ≤ 0.001 | 4.7 (1.9–12.0) | 1 (10.0) | 99 (4.8) | 0.4 | 2.2 (0.3–17.6) | |

| Parenteral Exposure | Sharing object of personal use | 5 (15.6) | 580 (28.4) | 0.1 | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 4 (40.0) | 574 (28.2) | 0.4 | 1.7 (0.5–6.0) |

| Tattoo, piercing, dental treatment | 16 (48.5) | 780 (37.9) | 0.2 | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 5 (50.0) | 784 (38.4) | 0.4 | 1.6 (0.4–5.5) | |

| Blood transfusion | 1 (3.1) | 68 (3.5) | 0.9 | 0.9 (0.1–6.6) | 1 (10.0) | 73 (3.4) | 0.3 | 3.0 (0.4–24.0) | |

| Vertical transmission | 3 (9.1) | 12 (0.6) | ≤ 0.001 | 16.5 (4.4–61.4) | 0 | 15 (0.8) | 0.8 | – | |

| Partner with history of STD | 1(3.1) | 15 (0.7) | 0.1 | 4.2 (0.5–32.9) | 1 (10.0) | 15 (0.7) | ≤ 0.001 | 15.0 (1.8–126.2) | |

| Pregnancy outcomes | Weight<2500g | 7 (21.9) | 348 (16.8) | 0.5 | 1.3 (0.6–3.1) | 4 (40.0) | 348(16.7) | 0.05 | 3.3 (0.9–11.8) |

| Gestational age<37 weeks | 9 (27.3) | 325 (15.8) | 0.1 | 2.0 (1.0–4.4) | 3 (30.0) | 331 (15.9) | 0.2 | 2.3 (0.5–9.0) | |

In univariate analysis, HBV and HCV infections were significantly associated with variables related to parenteral exposure. The logistic regression models taking HTLV, HBV, and HCV seropositivity as dependent variables were not performed due to the low number of reactive samples.

In the final multiple logistic regression model (Table 4), the variables independently associated with HIV positivity were multiple sexual partners (OR 3.3; 95% CI: 1.1–9.2), history of domestic violence (OR 2.8; 95% CI: 1.1–6.9), syphilis co-infection (OR 2.6; 95% CI: 1.0–6.9), use of illicit substances (OR 2.5; 95% CI: 1.2–5.5), and low schooling (OR 2.3; 95% CI: 1.1–4.9).

Multiple logistic regression of risk factors for HIV infection in parturient women. Maternity hospital MCO e MRPJMMN, Salvador – Bahia, Brazil 2016–2017.

| Variable | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | ||||

| Multiple sexual partners | 4.4 | 1.7–12.0 | 3.3 | 1.1–9.2 |

| Sexual or domestic violence | 4.1 | 1.7–9.7 | 2.8 | 1.1–6.9 |

| Syphilis co-infection | 5.7 | 2.4–13.5 | 2.6 | 1.0–6.9 |

| Alcohol and/or drugs users | 3.7 | 1.8–7.6 | 2.5 | 1.2–5.5 |

| Low schooling (<8 years) | 3.3 | 1.7–6.6 | 2.3 | 1.1–4.9 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; the final model parameters: χ2 model: 288.27; 0.016 (Cox &Sell); 0.109 (Nagelkerke).

In this study, there was a high proportion of women with previous diagnosis of HIV and socio-demographic and behavioral risk factors for HIV/AIDS and other STDs in a context of vulnerability. Additionally, the presence of HTLV infection in the gestational period had a significant relationship with a history of stillbirth and low birth weight infants.

The mean age (27.6 years) of the study sample is above the national average for pregnant women (25.7).8 There was a statistically significant difference in the ages of HTLV-infected women (34.3 vs. 27.2, p=0.04) suggesting that the main HTLV transmission route in this population is sexual exposure, as already reported in previous studies. Globally, the incidence of HIV infection among women aged 15–49 years is estimated in 2%, and in 6% among young women aged 15–24 years. There were an additional 5.2 million newly infected women between 2010 and 2015, including 1.2 million in southern Africa.1 Likewise, in the United States, the incidence of HCV infection among women increased annually by 13% in non-urban cities and 5% in urban cities. This situation increases the number of pregnant women who can expose their infants to these infections.6

HIV seroprevalence (1.5%) in this study was higher than that reported by Nóbrega et al. (0.8%)9 in a previous study conducted in the city of Salvador in 2009, which detected a 61.4% of diagnosis during the antenatal period or at delivery. Our study, on the other hand, found a high proportion (64%) of HIV cases diagnosed before the current pregnancy, indicating that more women living with HIV are becoming pregnant. This was also observed in a National study8 and in a study with pregnant women from São Paulo in 2010.10

Considering only new cases (0.6%), this study detected a higher HIV rate in pregnant women (6 cases per 1000 LB), than that found in a similar population in Salvador (2.9–2.7 cases per 1000, with a peak of 3.7 in 2012) from 2003 to 2014.11 In this context, recent reports from Brazil since 2010 show HIV prevalence rates of 0.3% and 1.2% for pregnant12–16 and parturient women,17–19 respectively, varying according to population and region. However, national studies8,20 have shown the same prevalence (0.4%) for both groups of women. This prevalence is low compared with Latin American and the Caribbean countries, where HIV seropositivity among pregnant women ranged from 0.06% to 2.37% in 2017, according to available data from 28 countries. The Bahamas, Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago2 reported HIV seropositivity above 1%.

Our results indicate a high HIV prevalence in women with socioeconomic and behavioral vulnerabilities. Similar results were described by other authors, who found independent HIV risk factors in women with sexual risk behaviors (low adherence to condom use, multiple sexual partners and use of illicit drugs)21,22 and in those with situations of social vulnerability (victims of domestic violence and low schooling).8,9,17–19,21,23 Our findings demonstrate the same vulnerability pattern for HIV infection in women. The significant association between poorer antenatal care for HIV-infected women than that observed for the seronegatives reinforces the role of access to healthcare information and adherence to preventive actions as vulnerability markers.

Domingues et al.8 showed that HIV infection is associated with syphilis infection (adjusted OR: 4.7; 95% CI 2.01–11.21), similarly to findings of our study, although in a lesser magnitude (adjusted OR: 2.6; 95% CI 1.0–6.9). However, factors like persistent high-risk behavior and high rate of maternal syphilis (4.7%)24 in our study population have resulted in increased syphilis/HIV co-infection. Furthermore, authors like Fabbro et al.25 reported 3.3% of HIV/HTLV co-infection in pregnant women, whereas our study reported only one patient with HIV/HTLV co-infection who also had syphilis. The low proportion of viral co-infections in our study, despite the common transmission routes and similar risk factors in infected parturient women, indicates that other transmission mechanisms are required for the simultaneous presence of these infections, especially for retroviruses. Previous studies from Salvador showed a close association between co-infection by HIV and HTLV and intravenous drug use.26

The seroprevalence for HTLV (0.4%) was low compared to studies with parturient women in the state of Bahia (0.8–1%), Salvador (1991),7 Cruz das Almas (2007),27 and Ilhéus-Itabuna (2014).28 At national level, HTLV seroprevalence in pregnant/parturient women is heterogeneous and depends on the region. It ranges from 0.1% in Mato Grosso do Sul,7–29 Mato Grosso,7 Goiânia30 and Botucatu (SP)7 to 1.7% in Vitória (ES).21 HTLV screening in health institutions is performed only in the prenatal follow-up, but pregnant women show low level of information ablout previous tests. In addition, the lack of records of previous serological tests makes it difficult to evaluate the prevalence of this agent in this population. In our study, most women were unaware of having performed HTLV screening or did not have the result at the time of delivery.

A significant association between gestational outcomes (stillbirth and low birth weight history) and HTLV seropositivity was detected. Although we were unable to find any previous report on such findings,31 a potential mechanism to explain the negative impact of HTLV infection on pregnancy is the change in the placenta due to activation of apoptosis as a protective mechanism to the presence of the virus to avoid transplacental transmission. This type of response is more frequently found in the placentae of HTLV-1-positive women when compared to non-infected women.32 There is no conclusive evidence on HTLV transmission during pregnancy, but existing data suggest that some transplacental transmission of HTLV can occur, once up to 12% of non-breastfed children can be infected.32 In addition, pro-viral DNA HTLV-1 has been detected in umbilical cord's mononuclear cells, reinforcing the potential for viral transmission before or during delivery.32

The seroprevalence rates for HBV and HCV infections (0.4% and 0.1%, respectively) confirm the low prevalence of viral hepatitis in the general population of the NE region (lower than 2%).33 Both prevalence rates are similar to the results found in other Brazilian cities.10,13–16,18,20,34,35 This prevalence is in line with the prevalence of HBsAg among children under five years old, in Latin America and the Caribbean, except in Honduras, Panama, Ecuador, and Paraguay (1–1.5%) and Jamaica, Haiti, and Guyana (2.5%), where the prevalence is higher.2

Despite the low prevalence, screening of hepatitis infection and immunization of all pregnant women are necessary to reduce the probability of vertical transmission, which is responsible for about 90% of chronic hepatitis cases in children. We observed that 73.7% of the women had received at least one dose of anti-HBV vaccine in prenatal care and 26.3% were not vaccinated or were unaware of their vaccination status. The evaluation of vaccination coverage was inaccurate due to lack of registration of the vaccines use in the prenatal care card, and to the absence of parturient vaccine card at admission to maternities. This finding exposes a flaw in antenatal care to guide pregnant women about the relevance of vaccination and the need of its formal registration, and to allow health professionals to identify cases of delay or abandonment of vaccination schedule.

HCV infection during pregnancy is still poorly studied in Brazil, with rare reports on the prevalence of HCV in parturient women or VT rates. The prevalence rates of 0.1% active (viremic) HCV and 0.3% non-viremic HCV are similar to previous studies. One of them,36 performed at the MRPJMMN maternity hospital from 2009 to 2011, found a prevalence rate of 0.2% among pregnant women, while others in different Brazilian cities16,19,37–39 showed rates ranging from 0.1%16,19 to 1.6%.21 However, much of these prevalence estimates were calculated only by proportion of anti-HCV positive results, without confirmatory tests, which demonstrates that even considering only serological results for detection of HCV infection, prevalence rates were mostly low. The non-availability of treatment for hepatitis C during pregnancy and the high risk (50%–85%) of chronification of cases39 increases the relevance of early detection and implementation of efforts to educate pregnant women to prevent infection.

Globally, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) control has approaches to screening and monitoring in both the high risk and general population groups. In Brazil, since the creation of the National STD and AIDS Program (PN_DST/AIDS), in 1985, courses of action for the prevention of the vertical transmission of STDs were set. All the recommended actions toward these goals are available, free-of-cost-, in the public health services setting. Over the past two decades, initiatives like increased prenatal care coverage and rapid testing,40,41 and preparation of guidelines for prevention of VT42 have been implemented. Such efforts contributed to improved rates of detected infections such as HIV and hepatitis B and C in pregnant women and to the prevention of VT of HIV through prophylaxis of HBV by vaccination.

However, our findings indicate that there is still a need of permanent monitoring on the adequate implementation of such initiatives, especially for women presenting individual or social vulnerability, or those already living with STDs, as these inequalities are a barrier to accessing routine antenatal care. A Brazilian hospital-based study concluded that only a fifth of pregnant women receive this adequate care: 53.9% attended services before week 12 of gestation and 73% received an adequate number of antenatal care visits.

The main strengths of the study are the sample size, the use of confirmatory tests, and the use of a questionnaire applied in the period of hospitalization, which allowed to identify the main risk factors for acquisition of blood or sexually transmitted infections by parturient women in Salvador. The limitation of our study was the evaluation of pregnant women in referral maternity hospitals, which may contribute to the observed high HIV seroprevalence.

In conclusion, the seroprevalence rates of the screened viral infections in is an essential information for the proper monitoring of VT.21 Moreover, the characteristics of these infections, such as the prolonged silent period, high transmissibility, and potential for development of chronic diseases, coupled with a scenario of individual and social vulnerability, make the intensification and maintenance of preventive and therapeutic actions to reduce new cases of infection in women and their partners mandatory.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank our collaborative team from the maternity hospitals Climério de Oliveira, José Maria Magalhães Neto and all from the Laboratório de Pesquisa em Infectologia (LAPI), who provided a strong contribution to this work.

The study was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (Fapesb 9620/2015) and by the CAPES for the scholarship granted to the post-graduate student author.