Hodgkin-like ATLL is a rare variant of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), a disease caused by human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1). At admission, a 46-year-old female presented with lymphadenomegaly, lymphocytosis, slight elevation of LDH blood level, and acid-alcohol resistant bacilli in sputum and was being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis (Tb). She had lymphocytosis in the previous 20 months. Serology for HTLV-1 was positive. Lymph node was infiltrated by medium-sized lymphocytes with scattered Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells CD30+, CS1-4+, and CD79a+. Background cells were CD4+ and CD25+. A clinical diagnosis of favorable chronic ATLL was given. She was treated with chemotherapy but later progressed to acute ATLL and ultimately died. Hodgkin-like ATLL should be considered in the histological differential diagnosis with Hodgkin lymphoma since treatment and prognosis of these diseases are distinct. It is also important to search for HTLV-1 infection in patients with unexplained prolonged lymphocytosis.

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is a malignant tumor of mature T-cells caused by the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1), which responds poorly to chemotherapy. It is classified in four clinical types: smoldering, chronic, lymphomatous, and acute. The chronic type is also subdivided into favorable and unfavorable types, based on serum levels of urea, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and albumin.1

Ohshima et al. (1991)2 in Japan, described four cases of ATLL with Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg (HRS)-like cells in lymph nodes. Later on, the same group published 18 cases of early ATLL with HRS-like cells, and demonstrated that these cells were reactive and not infected by HTLV-1.3 It was also shown that they were very frequently infected by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).3 In western countries, cases of Hodgkin-like-ATLL have been rarely reported.4,5 Hodgkin-like T-cell lymphomas not associated with HTLV-1 have also been reported.6–9

Here we report a case of Hodgkin-like ATLL in which lymphocytosis was the first manifestation.

Case reportA 46-year-old black female patient was referred to the Hematological Unit of the University Hospital Prof. Edgard Santos, in Bahia, Brazil in January 2012 with confirmed HTLV-1 infection (ELISA positive confirmed by Western blot) and a history of cervical lymphadenomegaly in the previous month. She had had a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis three months before in another center and was on rifampicin and isoniazid. Her blood tests taken in the previous 20 months showed lymphocytosis varying from 10,000 to 13,700 lymphocytes/mm3. Physical examination revealed cervical and retroauricular lymphadenomegaly. No skin lesions were observed. Blood examination showed leukocytosis with mild lymphocytosis (5940lymphocytes/mm3). The blood levels of calcium, urea, and albumin were within the normal limits but the LDH was slightly elevated. Flow cytometry of peripheral blood revealed an expression of CD3, CD4, CD5, TCRαβ and CD2 with co-expression of CD25. The lymphoid cells were negative for CD7, CD8, TCRγδ, and for NK cell and B-cell markers. Serology for HIV was negative. Cervical and thoracic computed tomography (CT) showed cervical and thoracic enlarged lymph nodes and infiltration in the left lung; abdominal CT was normal. A lymph node biopsy was performed and a diagnosis of Hodgkin-like ATLL was given, clinically corresponding to a favorable chronic ATLL. It was decided that the treatment for ATLL should begin after Tb control, considering the high toxicity of the combined therapy and the fact that favorable chronic ATLL constitutes an indolent form of ATLL.1

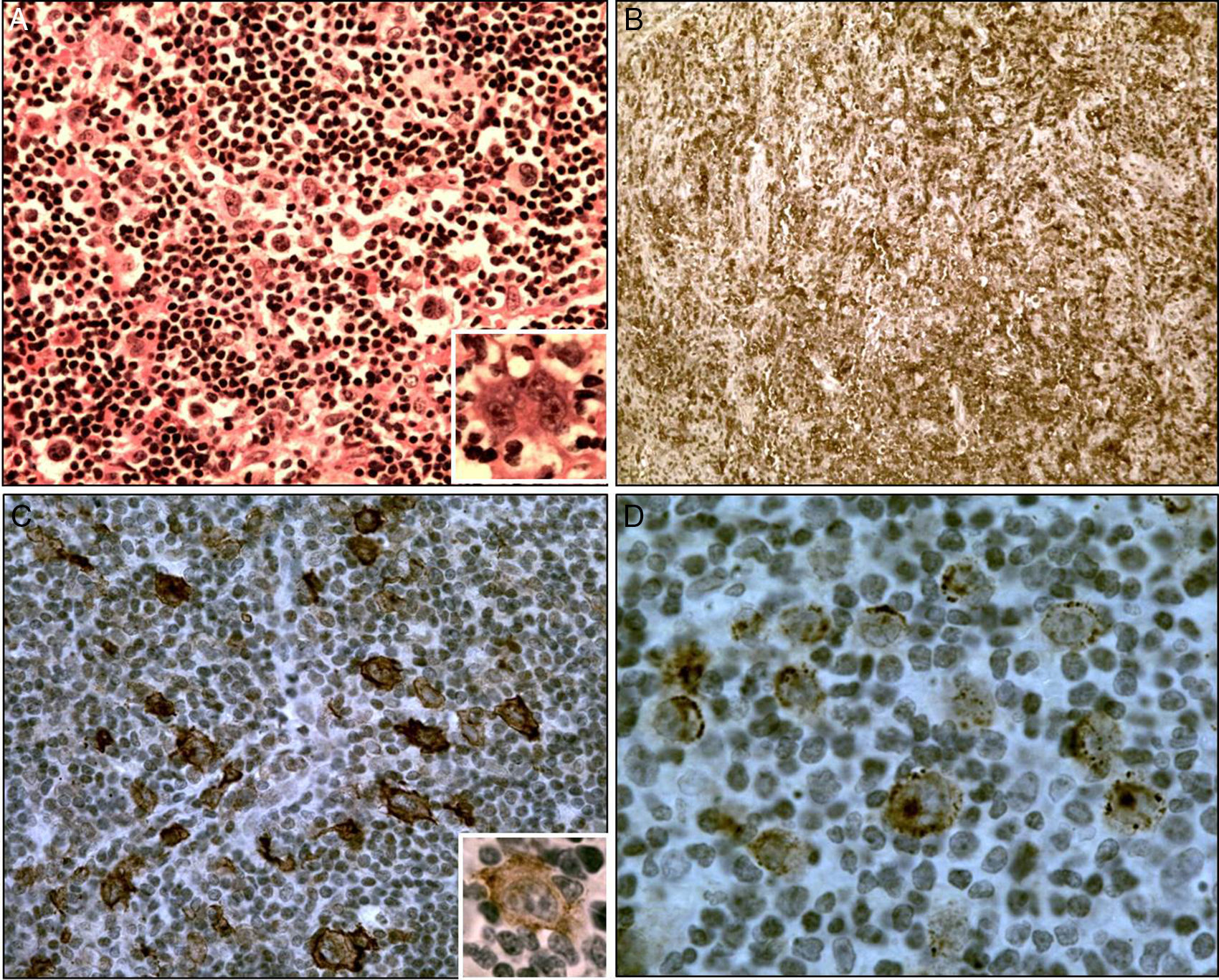

ATLL treatment was initiated six months after admission with zidovudine and interferon-α but due to important side-effects the drugs were discontinued and the patient began to be treated with six cycles of standard CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with partial response. After 14 months of Tb treatment, she was considered cured with no acid-alcohol resistant bacilli in sputum smears and negative culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The lymphocytosis reappeared after the end of chemotherapy and persisted until September 2013 varying from 4600 to 8000 lymphocytes/mm3. At this time, CT revealed enlarged cervical, thoracic and abdominal lymph nodes. Elevation of LDH, 2.5 times the upper normal limit, bilateral pleural effusion, slight peritoneal effusion and paresthesia and unilateral palpebral ptosis were also observed. She received two more salvage regimen of chemotherapy with partial response and died at home four months later. Pathologic findings – The lymph node exhibited diffuse infiltration of medium-sized atypical lymphocytes. Scattered in this background, HRS-like cells were seen, isolated or in small clusters (Fig. 1A). The medium-sized lymphocytes expressed CD3, CD4, CD5, CD25 (Fig. 1B), CD45RO (UCHL-1) and were CD8 negative. A marked reduction of CD7 expression was observed. The HRS-like cells were positive for CD30 (Fig. 1C), CS1-4 (Fig. 1D), CD79a, and focally for Bcl6 and CD20. The proliferative index as determined by Ki-67 immunostaining was 50%, especially in the giant cells. Both cell types were negative for CD10, CD15, CD21, CD23, and PD1.

(A) Hodgkin and Reed Sternberg-like cells in a background of small-to medium-sized lymphocytes, H&E stain, 400×; inset shows a RS-like cell with prominent nucleoli, 560×. (B) Background with CD25+ lymphocytes, 125×. (C) CD30+ Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg-like cells, 400×; in inset a CD20+ cell (800×). (D) CS1-4+ Hodgkin and RS-like cells, 800×.

The first manifestation of disease was lymphocytosis which persisted until after initiating chemotherapy but reappeared even before completion of this therapy. These data indicate that the lymphocytosis was related to ATLL and had appeared before the other manifestations, probably developing a few months before Tb. It is important to consider that the presence of persistent lymphocytosis in an HTLV-1 carrier may sometimes represent an early neoplastic phase of ATLL, as occurred in the current case.10,11 The case progressed from favorable chronic to acute ATLL, presenting neurological manifestations, elevation of the LDH level and pleural and peritoneal effusions.

The pathological differential diagnosis between Hodgkin-like ATLL and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) can be made by careful scrutiny of the background lymphoid cells. These cells are generally atypical in Hodgkin-like ATLL whereas they have normal morphology in classic HL. In the present case the background cells were atypical and showed CD3, CD4, CD5, and CD25 phenotypes with a marked reduction of CD7 positivity, as observed in ATLL1 and were negative for CD10 and PD1 enabling a differential diagnosis with angioimmunoblastic lymphoma, a disease that may also present HRS-like cells.6

Immunophenotypically, the HRS cells of classic HL are CD30+ and CD15+, can express the B-cell-associated marker CD20, and generally fail to express CD45 or T-cell associated antigens.8 The same is observed in the HRS cells of T-cell Hodgkin-like lymphomas.3–5,7 In the present case the HRS cells were CD30+, CD20+, CD79a+ but CD15 was negative as may occur in these lymphomas.3,4

The infection by EBV was detected by immunohistochemistry through the LMP-1 protein positivity as seen in other cases of Hodgkin-like ATLL.3,5 In EBV positive T-cell Hodgkin-like lymphomas, the HRS-like cells are believed to represent an expansion of EBV-transformed B cells, clonally unrelated to the lymphoma.8 Similarly, the HRS-like cells occurring in Hodgkin-like ATLL are reactive and not infected by HTLV-1.3

HTLV-1 infection causes immune system dysregulation with spontaneous lymphoproliferation and increased T-cell activation leading to production of high amounts of several cytokines.12 Due to this dysregulation HTLV-1 infected individuals are more prone to develop Tb as well as other infectious diseases. The severity of Tb observed in individuals with HTLV-1 infection is considered to be due to enhancement of Th1 inflammatory response, rather than to their decreased ability to control bacterial proliferation.13

In a previous study we showed a median survival time of chronic ATLL to be around 18 months.14 In one study, the use of antiviral therapy in chronic ATLL has resulted in a 5-year survival of 100% of the cases.15 Unfortunately, this patient could not be treated with antiviral drugs because of marked side-effects and had a survival of 24 months.

It is of fundamental importance for pathologists to recognize Hodgkin-like ATLL in order not to misdiagnose this entity with Hodgkin lymphoma since the treatment and prognosis of these diseases are quite distinct. Moreover, in endemic areas it is important to search for HTLV-1 infection in patients with an unexplained prolonged lymphocytosis that may represent the first manifestation of ATLL.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq) and Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (FAPESB).