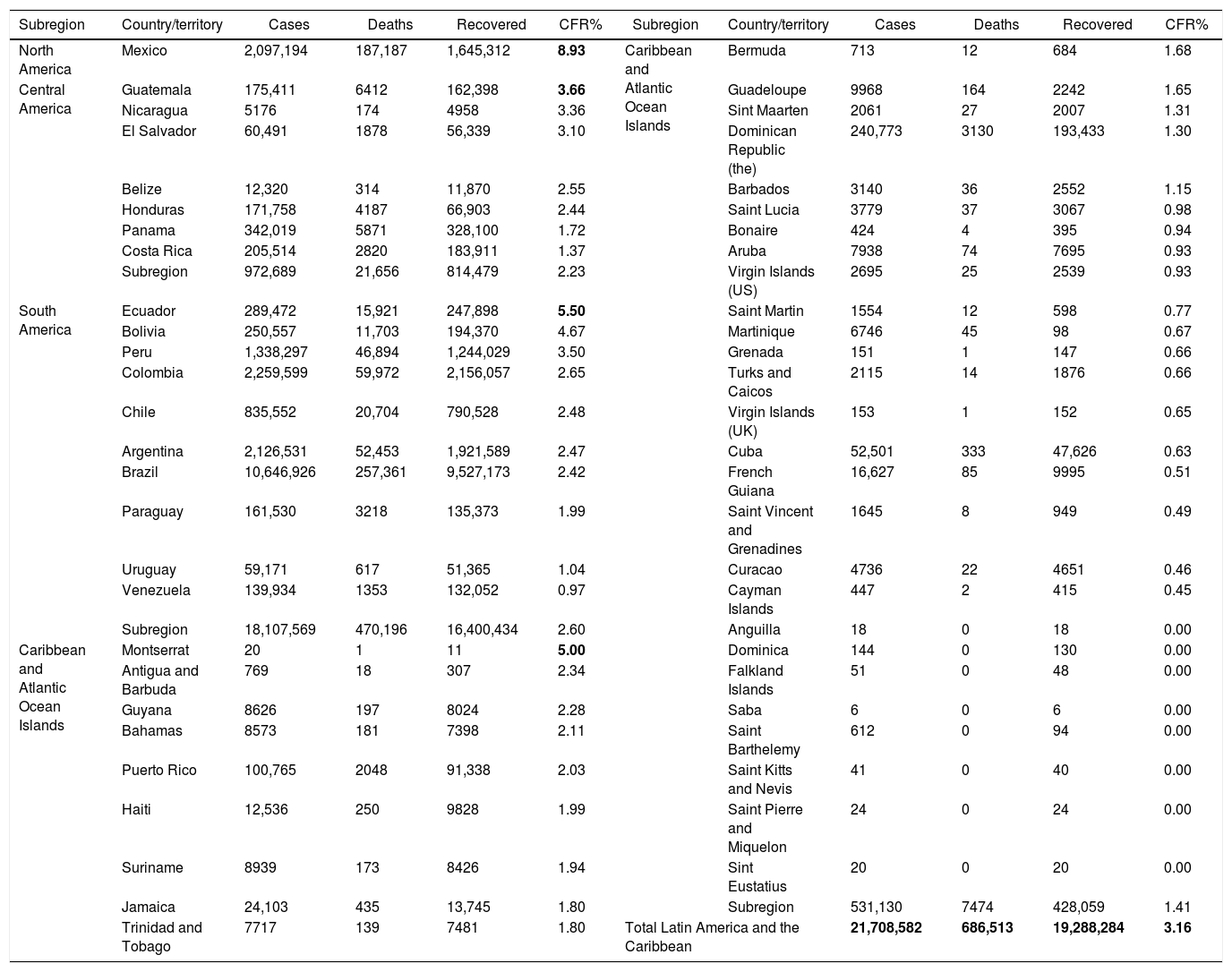

On February 25, 2020, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the etiological agent of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), was firstly confirmed in Brazil and Latin America, proceeding as an imported case from Italy.1,2 After one year of the lately declared pandemic, the COVID-19 has caused deep impacts in Brazil and the region.2 Up to March 4, 2021, a total of 21.7 million cases (out of 115 million in the world, 18.8%) (Table 1) have been reported and concentrated in the Latin American and Caribbean region, led by Brazil (10.6 million), as the third country in the world with more cumulated cases, after United States of America (28.8 million), and India (11.2 million).

Cumulative confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases reported by Countries and Territories in Latin America and the Caribbean, modified from the Pan American Health Organization (March 4, 2021).

| Subregion | Country/territory | Cases | Deaths | Recovered | CFR% | Subregion | Country/territory | Cases | Deaths | Recovered | CFR% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Mexico | 2,097,194 | 187,187 | 1,645,312 | 8.93 | Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean Islands | Bermuda | 713 | 12 | 684 | 1.68 |

| Central America | Guatemala | 175,411 | 6412 | 162,398 | 3.66 | Guadeloupe | 9968 | 164 | 2242 | 1.65 | |

| Nicaragua | 5176 | 174 | 4958 | 3.36 | Sint Maarten | 2061 | 27 | 2007 | 1.31 | ||

| El Salvador | 60,491 | 1878 | 56,339 | 3.10 | Dominican Republic (the) | 240,773 | 3130 | 193,433 | 1.30 | ||

| Belize | 12,320 | 314 | 11,870 | 2.55 | Barbados | 3140 | 36 | 2552 | 1.15 | ||

| Honduras | 171,758 | 4187 | 66,903 | 2.44 | Saint Lucia | 3779 | 37 | 3067 | 0.98 | ||

| Panama | 342,019 | 5871 | 328,100 | 1.72 | Bonaire | 424 | 4 | 395 | 0.94 | ||

| Costa Rica | 205,514 | 2820 | 183,911 | 1.37 | Aruba | 7938 | 74 | 7695 | 0.93 | ||

| Subregion | 972,689 | 21,656 | 814,479 | 2.23 | Virgin Islands (US) | 2695 | 25 | 2539 | 0.93 | ||

| South America | Ecuador | 289,472 | 15,921 | 247,898 | 5.50 | Saint Martin | 1554 | 12 | 598 | 0.77 | |

| Bolivia | 250,557 | 11,703 | 194,370 | 4.67 | Martinique | 6746 | 45 | 98 | 0.67 | ||

| Peru | 1,338,297 | 46,894 | 1,244,029 | 3.50 | Grenada | 151 | 1 | 147 | 0.66 | ||

| Colombia | 2,259,599 | 59,972 | 2,156,057 | 2.65 | Turks and Caicos | 2115 | 14 | 1876 | 0.66 | ||

| Chile | 835,552 | 20,704 | 790,528 | 2.48 | Virgin Islands (UK) | 153 | 1 | 152 | 0.65 | ||

| Argentina | 2,126,531 | 52,453 | 1,921,589 | 2.47 | Cuba | 52,501 | 333 | 47,626 | 0.63 | ||

| Brazil | 10,646,926 | 257,361 | 9,527,173 | 2.42 | French Guiana | 16,627 | 85 | 9995 | 0.51 | ||

| Paraguay | 161,530 | 3218 | 135,373 | 1.99 | Saint Vincent and Grenadines | 1645 | 8 | 949 | 0.49 | ||

| Uruguay | 59,171 | 617 | 51,365 | 1.04 | Curacao | 4736 | 22 | 4651 | 0.46 | ||

| Venezuela | 139,934 | 1353 | 132,052 | 0.97 | Cayman Islands | 447 | 2 | 415 | 0.45 | ||

| Subregion | 18,107,569 | 470,196 | 16,400,434 | 2.60 | Anguilla | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0.00 | ||

| Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean Islands | Montserrat | 20 | 1 | 11 | 5.00 | Dominica | 144 | 0 | 130 | 0.00 | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 769 | 18 | 307 | 2.34 | Falkland Islands | 51 | 0 | 48 | 0.00 | ||

| Guyana | 8626 | 197 | 8024 | 2.28 | Saba | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0.00 | ||

| Bahamas | 8573 | 181 | 7398 | 2.11 | Saint Barthelemy | 612 | 0 | 94 | 0.00 | ||

| Puerto Rico | 100,765 | 2048 | 91,338 | 2.03 | Saint Kitts and Nevis | 41 | 0 | 40 | 0.00 | ||

| Haiti | 12,536 | 250 | 9828 | 1.99 | Saint Pierre and Miquelon | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0.00 | ||

| Suriname | 8939 | 173 | 8426 | 1.94 | Sint Eustatius | 20 | 0 | 20 | 0.00 | ||

| Jamaica | 24,103 | 435 | 13,745 | 1.80 | Subregion | 531,130 | 7474 | 428,059 | 1.41 | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 7717 | 139 | 7481 | 1.80 | Total Latin America and the Caribbean | 21,708,582 | 686,513 | 19,288,284 | 3.16 | ||

Contrary to the initially considered by many experts, COVID-19 has caused a significant proportion of deaths. A total 2.5 million deaths have been reported so far (2.17% global fatality rate). In Latin America, this ranges up to 8.93% in countries such as Mexico or Ecuador with 5.0%. In Brazil, 257,361 deaths have been reported for a case fatality rate of 2.42%.

Over the last year, multiple new clinical findings have been detected, including smell and taste disorders, such as ageusia and anosmia, and diarrhea, among many others.3 The COVID-19 became a respiratory infection and a systemic condition that potentially affects many other organ and systems, including cardiovascular, neurological, and renal complications, among others. In at least 2–7% of the patients have required management at intensive care units (ICU), varying by countries, the risk profile of the patients (e.g., age and risk factors), as well as the healthcare system, including the availability of ICU beds, mechanical ventilation as well as critical care specialists, among other factors. COVID-19 varies from asymptomatic infection (in most cases) to severe disease that may lead to fatal outcomes.4

As expected, in countries such as Brazil and others in Latin America, the overlapping with other regional importance conditions began to be reported and represent a matter of concern, including HIV, tuberculosis, dengue, and other tropical endemic diseases.5,6 And these coinfections still need to be better understood in terms of their epidemiological and clinical impact.

In terms of laboratory capacity, Brazil and other Latin American countries have built up many skilled molecular biology laboratories that routinely perform the RT-PCR, based on international protocols, to diagnose the SARS-CoV-2. Also, a significant deployment of antigen and antibody tests has been employed in clinical and epidemiological settings, including multiple seroprevalence studies performed in different cities of Brazil and other Latin American countries.

This year, multiple challenges have been faced, including assessing new and specially repurposed drugs for their potential use as prophylaxis or treatment in different clinical conditions. So far, few of them have demonstrated usefulness in COVID-19, such as dexamethasone for patients requiring oxygen, including those on mechanical ventilation. On the other hand, chloroquine and ivermectin have not showed significant benefits in COVID-19. Unfortunately, these and other drugs are widely used in the region, despite the advice against by infectious diseases societies for the region, after the evidence assessment of their utility.

Also, in December 2020, many countries detected and observed the threat of the so-called new variants of concern of the SARS-CoV-2 (VOC) that have been associated with the increase in transmission, as reported in the United Kingdom and South Africa with the VOCs 501Y.V1(B.1.1.7) and 501Y.V2(B.1.351), respectively. These new strains are likely to be more transmissible and may also impact the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines negatively, still to be fully confirmed. Precisely Brazil is one of the countries that in January 2021 reported the VOC P.1(501Y.V3), now spreading to other countries of Latin America, such as Colombia, Suriname, Venezuela, Peru, and Argentina. This emerging situation resulted in new restrictions on air travel to and from these countries.7 The VOC P.1 was first reported by Japan from two travelers from Manaus, one of Brazil’s most important rainforest city. This shows the difficult found in Latin American countries, including Brazil, to genotype and identify VOC that might be spreading through the countries in the continent.

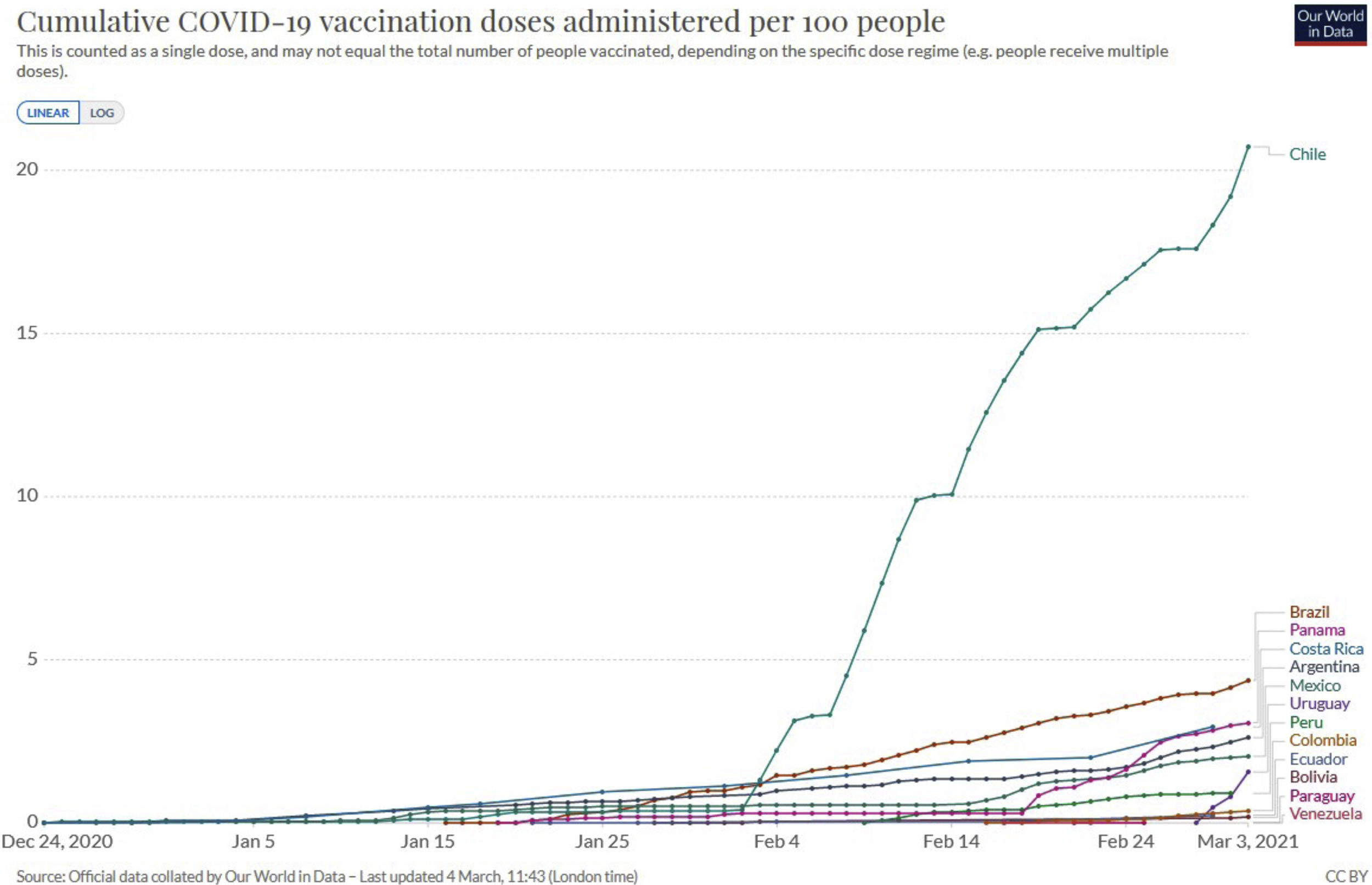

Concurrently, ending 2020/beginning 2021, multiple countries started their vaccination plans using different COVID-19 vaccines, including Brazil and most Latin American territories. In South America, more than 14.2 million doses have been applied, more than 9 million in Brazil (Fig. 1). Vaccines such as Comirnaty BNT162b2 (Pfizer/Biontech), AZD1222 (or Covishield) (AstraZeneca/Oxford), CoronaVac (formerly PiCoVacc) (Sinovac), BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm), and Sputnik V (Gamaleya Research Institute), among many other arriving, are being used in the region, expecting favorable results, based on phase 3 and target trials already published showing high efficacy and even effectiveness for them. Still, the efficacy and effectiveness of these vaccines need to be assessed carefully under the scenario of the VOCs.7

Additionally, and not least important, as previously discussed by our group,2 the political scenario has not been friendly for evidence-based decisions. That was mostly the situation in Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, and Venezuela, among others were not scientifically supported interventions recommended by high-rank stakeholders. Some of them have not broadly followed the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 People who refuse to practice COVID-19 preventive measures, such as wearing a mask, hand hygiene, physical distance, remaining in respiratory isolation at home when affected by the disease and not participating in agglomerations are largely responsible for the critical social and effective consequences that affect our countries in Latin America.

It is known that the solution, already experienced by countries such as the USA, United Kingdom and Israel, is the adoption of preventive measures by the entire population, together with the rapid mass vaccination of the population. Unfortunately, this target seems to be far for most Latin American countries yet.

Even with effective vaccines, multiple measures will need constant assessment and continuing use in Latin America, including selective quarantine for specific territories and periods, isolation, physical distancing, correct use of facial mask, hand washing, controlled rooms capacity, among others. Still, many work and study activities should be carried out virtually.2

Finally, the critical role played by the scientific societies, giving proper support and advice, such as the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases (SBI), in addition to the international organizations, such as the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) and the WHO, have helped to slow the number of new cases expected, define cases, detect them, and especially with the development of evidence-based clinical guidelines, appropriate clinical management, including diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Over this first year, many lessons have been learned from different points of view. Very sadly, many colleagues and health professionals have died working in the first line, and some have survived with sequelae. Physicians in Brazil and Latin America are working hard to face the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and hopefully move into the transition to a new “normal” world that may firstly control this emerging coronavirus effectively over the course of the next few months and years, sooner than later. For the moment of proofs correction of this Editorial (March 17, 2021), Brazil reached to 11.6 million cases, becoming the second country in the world with highest cases after USA (29.5 million cases), and facing one of the worse health crises due the collapse of health services.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.