Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) comprise several pathogens with a complex profile of virulence, diverse epidemiological and clinical patterns as well as host specificity. Recently, an increase in the number of NTM infections has been observed; therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics and outcomes of these infections.

MethodsWe included patients with NTM infections between 2001–2017 and obtained risk factors, clinical features and outcomes; finally, we compared this data between slowly growing (SGM) and rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM).

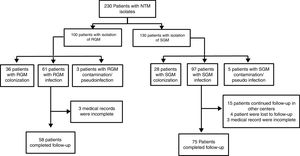

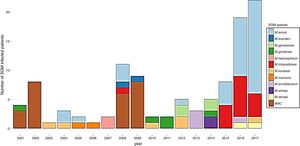

ResultsA total of 230 patients were evaluated, 158 (69%) infected and 72 (31%) colonized/pseudoinfected. The average annual incidence in the first 11 years of the study was 0.5 cases per 1000 admissions and increased to 2.0 cases per 1000 admissions later on. The distribution of NTM infections was as follows: bloodstream and disseminated disease 72 (45%), lung infection 67 (42%), skin and soft tissue infection 19 (12%). Mycobacterium avium complex was the most common isolate within SGM infections, and HIV-infected patients were the most affected. Within RGM infections, M. fortuitum was the most common isolate from patients with underlying conditions such as cancer, type-2 diabetes mellitus, presence of invasive devices, and use of immunosuppressive therapy. We did not find significant differences in deaths and persistent infections between disseminated SGM infection when compared to disseminated RGM infection (42% vs. 24%, p=0.22). However, disseminated SGM infection required a longer duration of therapy than disseminated RGM infection (median, 210 vs. 42 days, p=0.01). NTM lung disease showed no significant differences in outcomes among treated versus non-treated patients (p=0.27).

ConclusionsOur results show a significant increase in the number of Non-tuberculosis-mycobacteria infections in our setting. Patients with slow-growing-mycobacteria infections were mainly persons living with human immunodeficiency virus . Older patients with chronic diseases were common among those with rapidly-growing-mycobacteria infections. For non-tuberculosis-mycobacteria lung infection, antibiotic therapy should be carefully individualized.

There are around 150 species of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), of which approximately 80 are slow-growing mycobacteria (SGM) and 70 are rapid-growing mycobacteria (RGM).1 NTM are ubiquitous in environments such as soil, animals, residential tap water, and health care facility water systems.2–4 They are transmitted by aerosol, dust, ingestion, skin inoculation, and recently reported by human to human transmission in a cystic fibrosis patient.5 Despite this wide distribution, only a minority of all species are significant pathogens for humans.1 An increment in the number of cases and a differentiated geographical and climatic predisposition has been noted recently.6–9 The NTM cause diverse clinical manifestations such as lung infections, central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI),10,11 skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), otomastoiditis,12 among others. In addition, they cause disease in a variety of clinical settings (e.g., associated with fish markets,13,14 nosocomial outbreaks,15,16 and disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients17,18).

The association of AIDS with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection has been well documented, and its incidence has declined with the widespread availability of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART).19 The treatment of these infections is prolonged, and a species-specific multidrug regimen is required; however, successful treatment has been limited (51–60%), due to the diverse virulence profile among the species and a high rate of antibiotic discontinuation caused by adverse events.20,21 Recommendations for the management of lung infections are better defined,22,23 although limited to extrapulmonary infections. Because of its increasing prevalence, variability among geographic regions, diversity of host, clinical manifestation among and within RGM and SGM groups, as well as poor outcomes, knowledge of these parameters in our population is needed. In Mexico, the information about NTM is scarce, with only a reported outbreak of 22 patients with post-surgical nasal cellulitis due to M. chelonae and 12 HIV-infected patients with MAC infection several years ago, both reported by our group.24,25 The objective of this study was to evaluate the epidemiologic profile, clinical and microbiologic characteristics, and treatment outcomes related to RGM and SGM infections.

MethodsA retrospective study was conducted at a tertiary care referral medical center in Mexico City with 211 beds for adult medical and surgical patients. We searched the database of the laboratory of Clinical Microbiology to identify patients in whom an NTM was isolated between January 2001 and December 2017; medical records were reviewed to obtain clinical data, radiographic presentation, and treatment outcomes. We performed a description of these parameters for RGM and SGM classifying them in clinical syndromes, and a comparison between them was performed. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board, and because of its retrospective nature, informed consent was exempted.

DefinitionsNTM Lung disease was defined according to the criteria of the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).22 CLABSI was defined according to published criteria for catheter-related bloodstream infections released by IDSA.26 Slow-growing mycobacterial disseminated disease was considered if MAC or other SGM was recovered from blood, bone marrow, spleen, liver, cerebrospinal fluid, or another sterile site. In the case of a positive culture from a respiratory sample, feces, lymph node, and skin and soft tissue, an additional isolate from a secondary organ was needed to define it as disseminated disease. RGM disseminated disease was defined according to a previous report.27 SSTI was defined as isolation of NTM from subcutaneous nodules, abscesses, ulcers, wounds, or recovery from bones, joints, or tendons. For simplification, localized lymphadenitis was considered in this group. Nosocomial infection due to NTM was defined as an infection that may be detected during the hospital stay or might manifest after discharge.28 Colonization was defined as the establishment of NTM within the patient's microflora without evidence of disease or tissue invasion. A pseudoinfection or contamination was defined as a positive culture result from a patient without evidence of true infection or colonization, as it has been previously described.28

Microbiological identificationBlood and sterile fluids were inoculated on Aerobic/F medium (Becton Dickinson, Shannon, County Clare, Ireland), which were incubated in the BACTEC FX equipment (Becton Dickinson), if the Gram stain from positive samples showed beaded Gram-positive rods, a microscopic examination by Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed; if positive, subcultures were made on liquid culture media using the Bactec MGIT 960 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD.USA) and in Löwenstein-Jensen agar. For respiratory specimens, skin/soft tissue, lymph node and stools, after appropriate decontamination, the same procedures were performed. The GenoType Mycobacterium CM/AS line probe assays (Hain Lifescience, GmbH, Nehren, Germany) was used for identification; in case of unsuccessful identification, analysis of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene was performed.

Treatment outcomesCure was defined as improvement of signs and symptoms during treatment, and when available, documented negative mycobacterial cultures after appropriate treatment; clinical relapse/reinfection when symptoms and signs of active infection and recovery of the same species after improvement with proper time of therapy; failure when presence of symptoms and signs of NTM infection despite appropriate treatment were recorded. Death associated to NTM infection was considered directly (when the patient died because of a well-defined infection caused by NTM) or indirectly (death due to other causes such as cardiovascular disease, hepatic failure, respiratory failure, among others but in the presence of active NMT infection or receiving treatment for it).

Data analysisThe clinical characteristics and demographic data were analyzed with descriptive statistics. Comparisons among groups of patients with RGM and SGM infections were performed with the chi-square test for categorical variables or Fisher's exact test when appropriate, the continuous variables with the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. p-Value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed with R version 3. 4. 3 (R Core Team [2017])

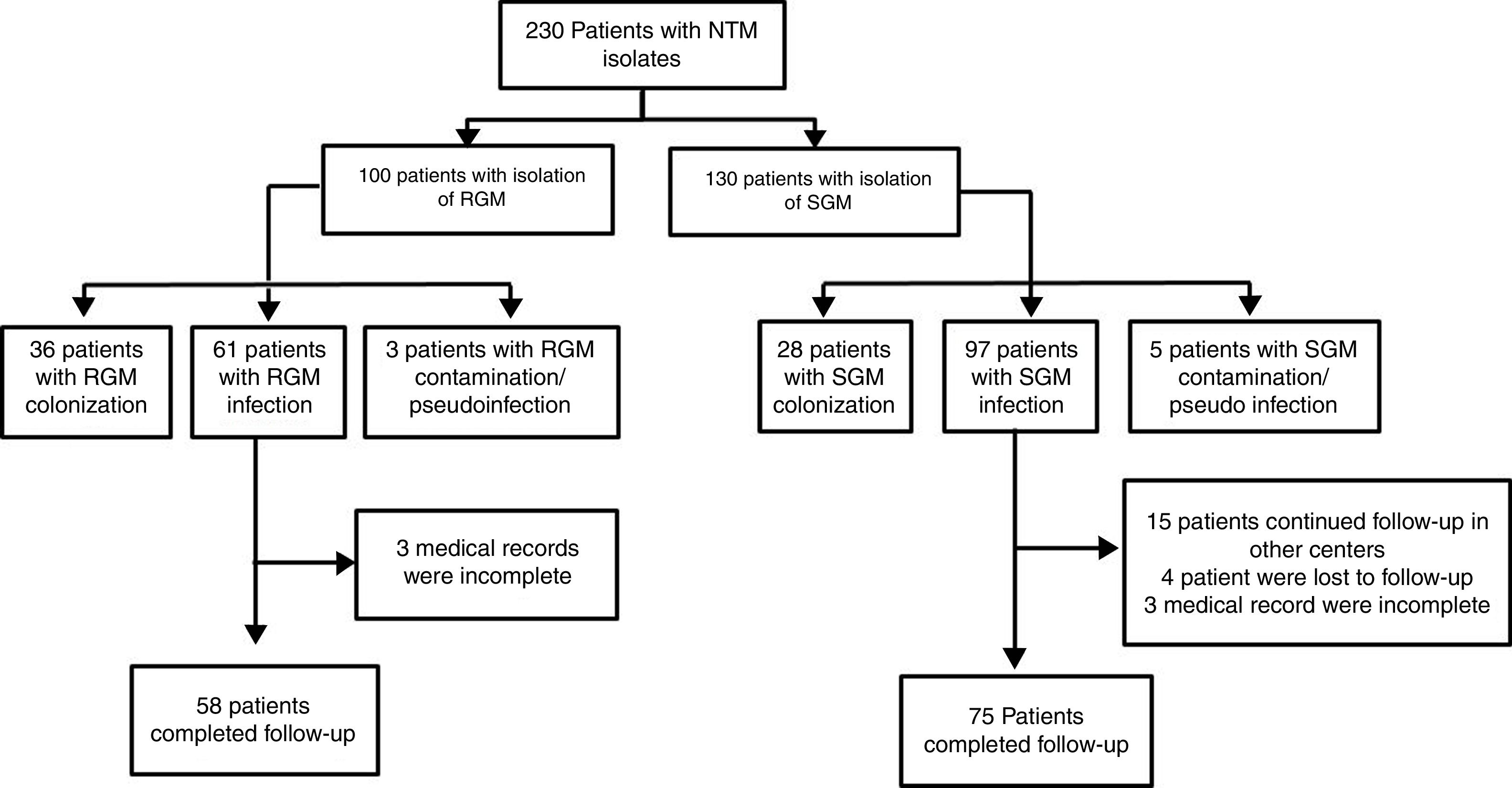

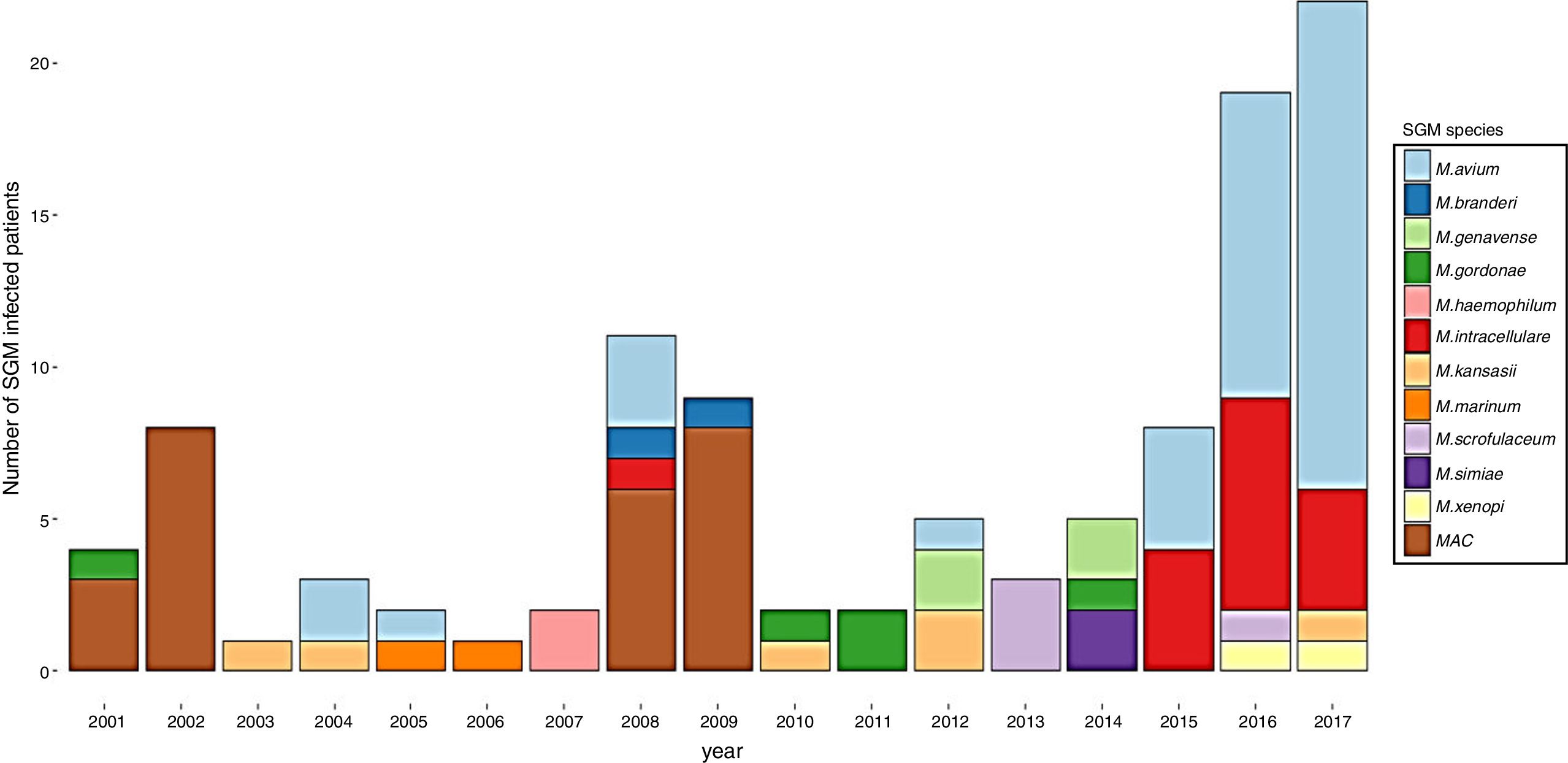

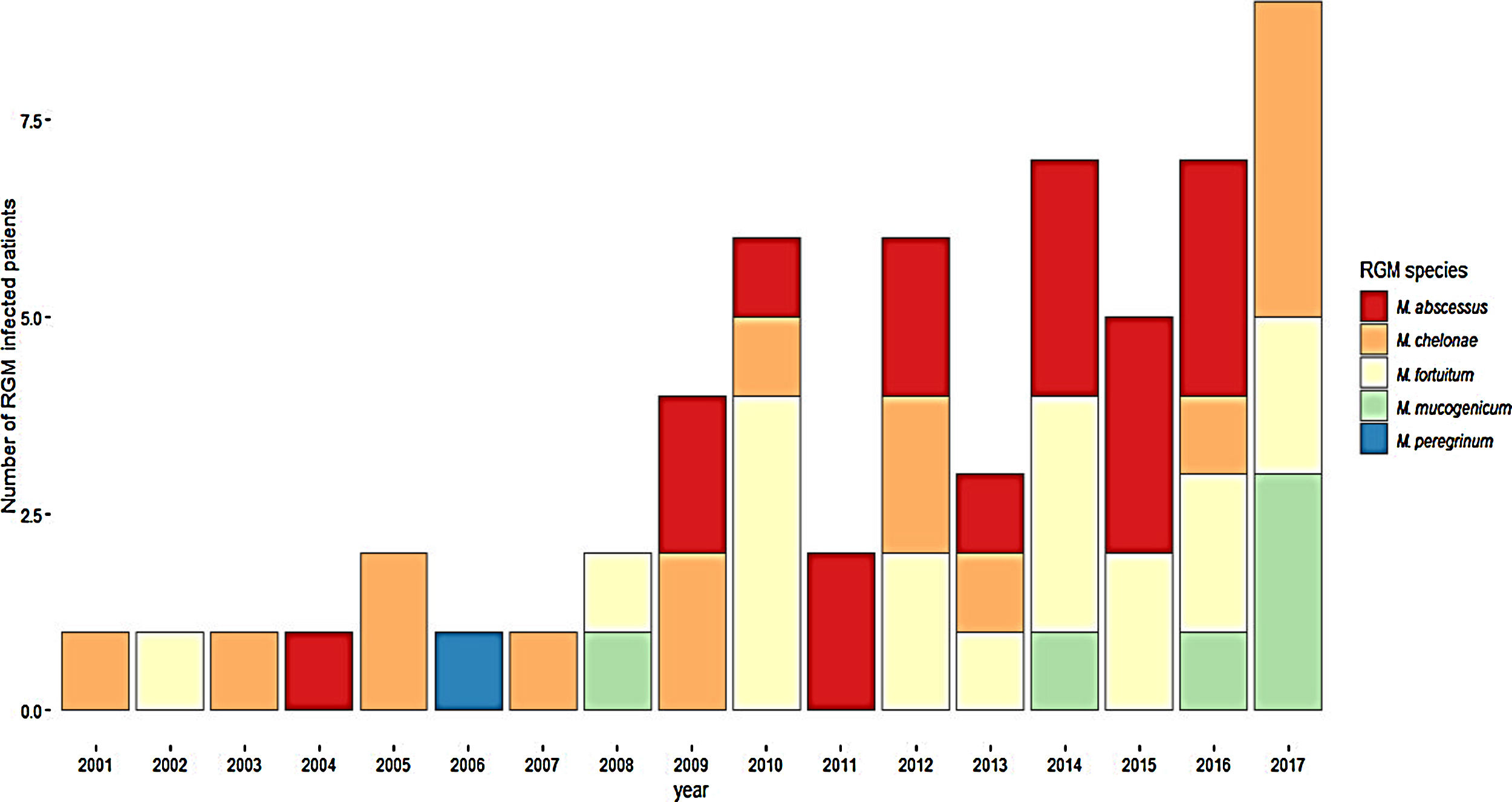

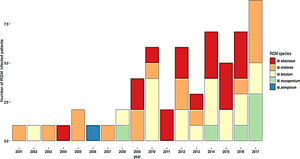

ResultsDuring the study period, 230 patients had NTM isolates; 130 patients had SGM isolates, of whom 97 were considered infected (Fig. 1), and 100 patients had RGM isolates, of whom 61 were considered infected. The average annual incidence of NTM infections in the period 2001–2011 was 0.6 per 1000 admissions for SGM (range, 0.2–1.6) and 0.3 per 1000 admissions for RGM (range, 0.2–1.5); from 2012–2017, the incidence increased to 1.9 per 1000 admissions (range, 0.9–4.8) and 1.1 per 1000 admissions (range, 0.3–2.1), respectively (Figs. 2 and 3). Among all SGM infections, MAC was the most frequent species throughout the study; M. avium and M. intracellulare were fully identified since 2010. In the RGM group, M. chelonae was the most frequent species during the first five years; after that, M. fortuitum and M. abscessus were the predominant species. The trends for infection or colonization were similar among SGM and RGM during the study period (Supplementary data Figs. 1 and 2). The patients infected and available to be followed up (SGM 75 and RGM 58) had a median follow-up time of 410 days (range, 240 to 5040 days).

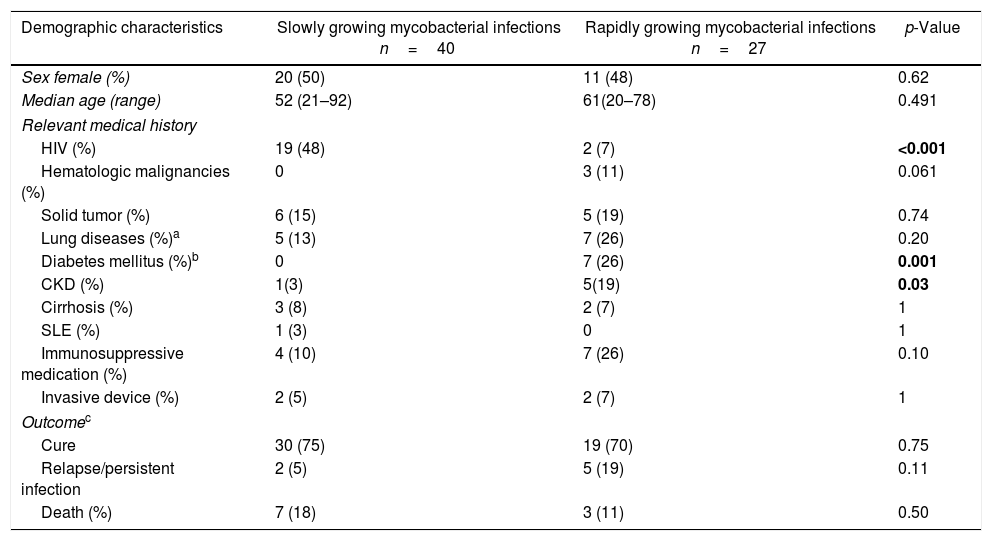

Sixty-six patients had lung infections, of whom 39 (59%) were SGM and 27 (41%) RGM (Table 1). The predominant mycobacteria in SGM infections was MAC in 31/39 (79%) patients, and a significant proportion of patients were HIV-infected. M. kansasii and M. scrofulaceum were the etiologic agents in three patients with structural lung diseases, and in two with immunosuppression without HIV infection, respectively. Among patients infected by RGM, M. abscessus and M. fortuitum were isolated in two-thirds of the patients (18/27). The patients with RGM infections had a significantly higher proportion of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) than patients with SGM infections. The predominant radiographic patterns in SGM infections were nodular-bronchiectatic and consolidation in 72% (28/39). In RGM infections, the radiographic changes were nodular, consolidation, and interstitial in 52% (14/27). Among 66 patients evaluated, only 36 (55%) received treatment despite meeting the ATS/IDSA criteria. The reasons for not receiving therapy were mainly drug interactions and physician's or patient's decision. There were no differences in the proportion of cure, relapse/persistent infection, and death between treated and not treated patients (Supplementary data Table 1). The same analysis adjusted for RGM or SGM lung infections showed similar results (Supplementary data Table 2 and 3). There was a small significant difference toward more days of hospitalization for RGM than SGM lung infections (median; 17 vs. 13 days, p=0.04). The deaths in this group of infections were mainly related to respiratory failure because of underlying lung disease in 70% (7/10).

Demographic, clinical characteristics and outcomes of 67 nontuberculous mycobacteria lung infections.

| Demographic characteristics | Slowly growing mycobacterial infections n=40 | Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections n=27 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex female (%) | 20 (50) | 11 (48) | 0.62 |

| Median age (range) | 52 (21–92) | 61(20–78) | 0.491 |

| Relevant medical history | |||

| HIV (%) | 19 (48) | 2 (7) | <0.001 |

| Hematologic malignancies (%) | 0 | 3 (11) | 0.061 |

| Solid tumor (%) | 6 (15) | 5 (19) | 0.74 |

| Lung diseases (%)a | 5 (13) | 7 (26) | 0.20 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%)b | 0 | 7 (26) | 0.001 |

| CKD (%) | 1(3) | 5(19) | 0.03 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 3 (8) | 2 (7) | 1 |

| SLE (%) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 |

| Immunosuppressive medication (%) | 4 (10) | 7 (26) | 0.10 |

| Invasive device (%) | 2 (5) | 2 (7) | 1 |

| Outcomec | |||

| Cure | 30 (75) | 19 (70) | 0.75 |

| Relapse/persistent infection | 2 (5) | 5 (19) | 0.11 |

| Death (%) | 7 (18) | 3 (11) | 0.50 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

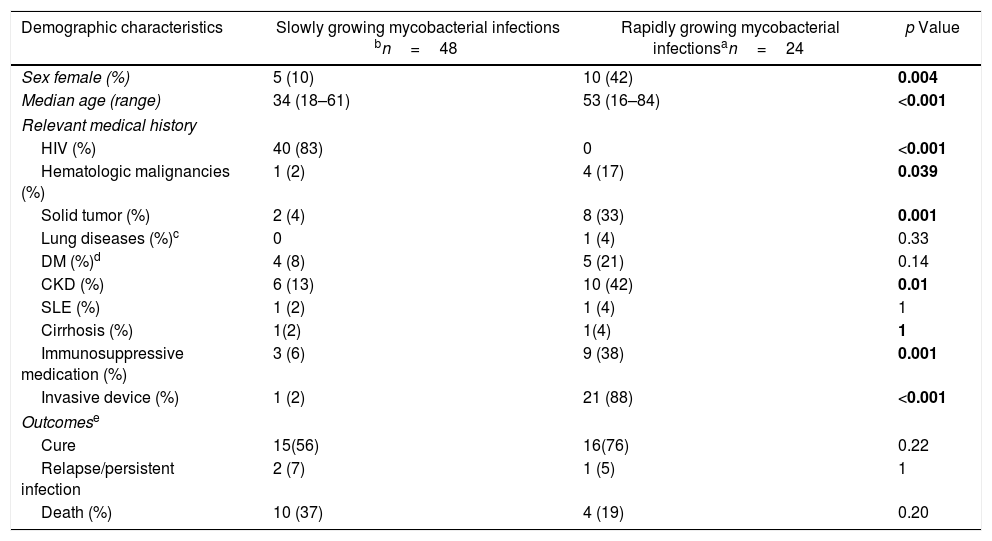

Bloodstream and disseminated disease together accounted for 46% (72/158) of all NTM infections. SGM caused about 70% (48 patients) of disseminated diseases, and the predominant species was MAC with M. avium representing 67% (26 of 39 MAC infections). The patients with SGM disseminated disease were mainly young males, and 83% (40/48) were HIV-infected (Table 2). M. kansasii was the cause of disseminated disease in one patient with leukemia, and M. branderi in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Lung involvement in SGM disseminated disease occurred in 48% (23/48), mainly showing consolidation in 61% (14/23). Patients with RGM infections were predominantly caused by M. fortuitum in 46% (11/24) and M. abscessus in 25% (6/24). Patients with RGM had a history of underlying diseases such as CKD, cancer, and use of immunosuppressive therapy (five patients with cancer chemotherapy, three with steroids, and two with immunomodulators) during the infectious episode. The use of invasive devices was more frequent in patients with RGM. The source of BSI was central venous catheter in 66% (12/18), eight patients had nontunneled hemodialysis catheters, and four had tunneled catheters for chemotherapy. Cholangitis associated with biliary devices was the source of RGM BSI in 22% (4/18) of patients. Lung involvement in RGM disseminated disease occurred in 3/6 patients, of whom two had consolidative radiographic patterns, and one a nodular pattern. The length of treatment was significantly longer for SGM than RGM disseminated disease (SGM median 210 days vs. RGM median 42 days, p=0.01). Although the proportion of deaths in SGM disseminated disease was higher than in RGM infections (21% vs. 17%), there were no significant differences in the rate of mortality or relapse/persistent infection between SGM and RGM BSI and disseminated disease (Table 2). Deaths in the SGM infection group were directly related to the disseminated disease in the setting of HIV infection in 8/10 patients. On the other hand, in RGM infections, only one death was directly related to mycobacteremia.

Demographic, clinical characteristics and outcomes of 72 bacteremia and disseminated disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria.

| Demographic characteristics | Slowly growing mycobacterial infections bn=48 | Rapidly growing mycobacterial infectionsan=24 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex female (%) | 5 (10) | 10 (42) | 0.004 |

| Median age (range) | 34 (18–61) | 53 (16–84) | <0.001 |

| Relevant medical history | |||

| HIV (%) | 40 (83) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Hematologic malignancies (%) | 1 (2) | 4 (17) | 0.039 |

| Solid tumor (%) | 2 (4) | 8 (33) | 0.001 |

| Lung diseases (%)c | 0 | 1 (4) | 0.33 |

| DM (%)d | 4 (8) | 5 (21) | 0.14 |

| CKD (%) | 6 (13) | 10 (42) | 0.01 |

| SLE (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 1 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 1(2) | 1(4) | 1 |

| Immunosuppressive medication (%) | 3 (6) | 9 (38) | 0.001 |

| Invasive device (%) | 1 (2) | 21 (88) | <0.001 |

| Outcomese | |||

| Cure | 15(56) | 16(76) | 0.22 |

| Relapse/persistent infection | 2 (7) | 1 (5) | 1 |

| Death (%) | 10 (37) | 4 (19) | 0.20 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; CKD, chronic kidney disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

There were 18 bacteremias and 6 disseminated disease, three patients with disseminated disease for M. fortuitum had blood stream infection as well.

three patients in the RGM and 21 in the SGM group were missed to follow-up (see Fig. 1). SGM: MAC (9), M. avium (26), M. intracelulare (4), M. branderi (2), M. genavense (1), M. haemophilum (1), M. kansasii (2), M. scrofulaceum (1) and M. simiae (2). RGM: M. abscessus (6), M. chelonae (4), M. fortuitum (11), M. mucogenicum (2) and M. peregrinum (1).

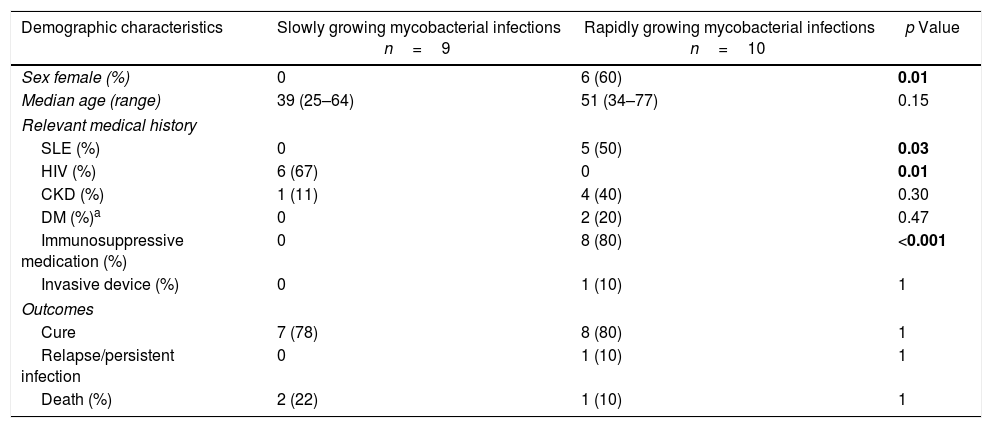

There were 19 episodes of SSTI, of which 9 (47%) were caused by SGM. All patients were males (9/9), predominantly with MAC infection (5/9) with a history of HIV infection (6/9). M. gordonae was the etiologic agent in a patient with Crohn's disease and one with HIV, M. marinum was the cause in one patient with HIV infection and in another patient without any identifiable predisposing factor (Table 3). M. chelonae (7/10) was the most common mycobacteria in SSTI caused by RGM. The patients were mainly females with prior immunosuppressive use (steroids at immunosuppressive dosage; >15mg/day) in 8/10 patients and half of the patients had SLE. There were no episodes of relapse/persistent infection nor differences in the proportion of deaths between the groups of mycobacteria (Table 3). The deaths in this group of infections were not directly related to infection; instead, they were associated with the underlying diseases.

Demographic, clinical characteristics and outcomes of 19 skin and soft tissue infections for nontuberculous mycobacteria.a

| Demographic characteristics | Slowly growing mycobacterial infections n=9 | Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections n=10 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex female (%) | 0 | 6 (60) | 0.01 |

| Median age (range) | 39 (25–64) | 51 (34–77) | 0.15 |

| Relevant medical history | |||

| SLE (%) | 0 | 5 (50) | 0.03 |

| HIV (%) | 6 (67) | 0 | 0.01 |

| CKD (%) | 1 (11) | 4 (40) | 0.30 |

| DM (%)a | 0 | 2 (20) | 0.47 |

| Immunosuppressive medication (%) | 0 | 8 (80) | <0.001 |

| Invasive device (%) | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Cure | 7 (78) | 8 (80) | 1 |

| Relapse/persistent infection | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 |

| Death (%) | 2 (22) | 1 (10) | 1 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; CKD, chronic kidney disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

HIV-infected patients accounted for 42% (67/158) of all patients infected by NTMs, remarkably, in each group of infections caused by SGM, HIV-infected patients represented proportions around 48% to 83%. However, median CD4+ cell count was significantly different in our patients according to the extension of the disease: lung infection, 78cells/μL (range, 2–267); disseminated disease, 14cells/μL (range, 1–200); SSTI, 144cells/μL (range, 49–879) (p<0.001). Almost all HIV patients presented with symptoms of disseminated disease, as well as the presence of other disseminated opportunistic infections such as M. tuberculosis (4/67), Kaposi sarcoma (5/67), histoplasmosis (3/67), and AIDS-associated malignancies (non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, 2/67); 97% of HIV infected patients received specific treatment for NTM infections associated with ART.

Thirty-one percent of the patients were considered as colonized (n=64) or contaminated/pseudoinfected (n=8); 56% of them (40/72) had RGM infections, and 44% (32/72) had SGM. Their clinical characteristics are shown in Table 4 of the Supplementary data.

DiscussionOur data show a growing trend in the number of NTM infections in this tertiary care center. Patients with SGM infections were mainly people living with HIV, with M. avium complex being the most common pathogen in this group. However, other SGM species were also associated mostly with HIV-infected patients, and the severity in the presentation was related to the degree of immunosuppression reflected by the CD4 count. For RGM infections, we observed mostly older patients with chronic diseases such as type 2 DM, cancer, CKD, SLE, as well as other conditions such as use of immunosuppressive therapy and invasive medical devices. Among these infections, M. fortuitum was the most common agent, and 38% of the latter isolates were considered as colonizers.

The increase of NTM infections since 2012 of both RGM and SGM in this setting is similar to what other institutions have recently reported. A multi-regional survey conducted in the USA reported a prevalence rate of 1.78 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1983,6 compared to 27.9 in a more recent study in 2010, with a predominance of cases from southeastern and coastal regions.7 The increasing prevalence of NTM could be explained by several additional factors such as improved identification techniques, age of the population living with chronic diseases, better options for treatment of chronic diseases, use of immunosuppressive medication, use of central lines for hemodialysis or chemotherapy and other invasive devices.1,23

Pulmonary infections caused by SGM were mainly associated with MAC, and the hosts were HIV-infected patients, the typical radiographic pattern was nodular-bronchiectatic. This pattern was different from lung infection secondary to MAC disseminated disease, which was mostly nodular or consolidation. The nodular bronchiectatic pattern has shown prognostic significance in MAC lung disease29; we observed only two patients with MAC lung infection with persistent disease after one year of treatment and both had a nodular radiographic pattern. There were no differences in the rates of death or relapse in patients who did not receive treatment, even if they met the criteria of the ATS/IDSA for therapy, which may be explained by the lack of prognostic value of these criteria. It should be emphasized that an individualized decision of treatment based on patient's underlying diseases is highly desirable in these complex cases. Similar findings have been described by others,30–33 and even patients who received antibiotic treatment have shown a higher risk of microbiologic and radiographic persistence.34 Pulmonary cases of RGM were mostly associated with underlying lung structural disease that is frequently observed in these patients. The predominant radiographic pattern was nodular and micronodular, and the most common pathogen was M. fortuitum; the nodular radiographic pattern has been recognized in patients with M. abscessus infection.35 Nonetheless, in a recent study from South Korea, M. abscessus was the most prevalent pathogen, and the predominant radiographic pattern was cavitary disease.21

In the last few years, a decreasing incidence in disseminated MAC disease has been described.19 However, in this study, we found an increase in the number of cases of young males living with HIV and SGM infection. We believe that this may be explained by a late entry to care of patients in our center (very low CD4 counts). Despite the effort to implement early ART in this population, we observed that only 56% of them were cured after treatment with clarithromycin, ethambutol and a fluoroquinolone. The poor prognosis of MAC complex disseminated disease has been shown previously, with mortality in the first year up to 69-fold more likely in comparison to the general population,20 and a low likelihood of a successful outcome, which may be as low as 40%.36 The patients with CLABSI caused by RGM were commonly receiving chemotherapy or were on hemodialysis, and the predominant microorganism was M. fortuitum. In an earlier case series of patients with cancer and CLABSI by RGM from Houston, Texas, M. mucogenicum was the most important pathogen isolated (39%). In another study from South Carolina, M. fortuitum was the most common (30.3%), followed by M. mucogenicum (27.2%).10,11 In our study, M. mucogenicum only caused two bloodstream infections; one was a CLABSI, and the other, secondary to an abscess compromising a colorectal tumor. Cholangitis caused by RGM has been reported rarely. We observed four patients with biliary tract infection associated with intra-biliary devices. All of them had bloodstream infections as complication, two died from refractory septic shock, one with M. chelonae and the other with M. abscessus and Aeromonas caviae. The NTM are a well-recognized cause of nosocomial outbreaks.15,16 We only had two cases of CLABSI caused by M. fortuitum coming from the same outer hemodialysis unit over one month, in which clonality was confirmed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

Half of the cases of SSTI caused by RGM suffered from SLE, all of them were on steroids and the most common agent was M. chelonae, which is similar to other recent reports.18,37 This finding suggests that this type of infection should be sought thoroughly in patients at risk.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective design with information gathered from medical records, which had 19% of cases missed upon follow-up, and the small sample size in some subgroups did not enable further evaluation. However, the patient diversity and the longtime of the analysis showed a clear profile of NTM infections in our center, results that may be shared by other referral centers. Our identification by nucleic acid probe assay does not allow differentiation within M. abscessus complex and MAC. In the latter, M. chimera identification is relevant because it has caused nosocomial outbreaks.15 However, in our study, NTM healthcare-associated infections were caused by RGM.

In conclusion, the incidence of NTM infections seems to be increasing; therefore, a constant vigilance of their epidemiology is needed since outbreaks or a higher number of infections in populations at risk could go unnoticed. The decision to treat patients with NTM isolates should be based on careful clinical judgment, particularly in lung infections weighing long-term and potentially toxic antibiotic treatment. Better strategies and simplified drug regimens assessed in randomized trials are needed, mainly for MAC disseminated disease.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.