The present study was designed to evaluate the molecular epidemiology of CTX-M producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae and Escherichia coli isolated from bloodstream infections at tertiary care hospitals in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Material and methodsA total of 231 nonduplicate Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from five Brazilian hospitals between September 2007 and September 2008. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by disk diffusion method according to the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. Isolates showing resistance to third-generation cephalosporins were screened for ESBL activity by the double-disk synergy test. The presence of blaCTX-M, blaCTX-M-15 and blaKPC genes was determined by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification and DNA sequencing. The molecular typing of CTX-M producing isolates was performed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Results and discussionNinety-three isolates were screened as ESBL positive and 85 (91%) were found to carry CTX-M-type, as follows: K. pneumoniae 59 (49%), E. cloacae 15 (42%), and E. coli 11 (15%). Ten isolates resistant for carbapenems in K. pneumoniae were blaKPC-2 gene positive. Among CTX-M type isolates, CTX-M-15 was predominant in more than 50% of isolates for K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae. PFGE analysis of CTX-M producing isolates showed the predominance of CTX-M-15 in 10 of 24 pulsotypes in K. pneumoniae, 6 of 13 in E. cloacae and 3 of 6 in E. coli. CTX-M-15 was also predominant among KPC producing isolates. In conclusion, this study showed that CTX-M-15 was circulating in Rio de Janeiro state in 2007–2008. This data reinforce the need for continuing surveillance because this scenario may have changed over the years.

Since the end of the 1990s, the CTX-M enzymes have spread among the continents, becoming the most prevalent in the world.1 Among CTX-M-type, specifically CTX-M-15 is the most widely distributed in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4 Particularly, several reports have shown that CTX-M-15-producing E. coli isolates are closely associated with a single clone disseminated worldwide, which is represented as sequence type (ST) 131 and serotype O25:H4.4,5 In K. pneumoniae, CTX-M-15 had been found in many countries associated with quinolone resistant strains that belonged to ST11.2,3,6

In South American countries (including Brazil), isolates harboring the CTX-M-2 have been the most frequent CTX-M-type detected.7–9 The occurrence of blaCTX-M-15 was first reported in clinical isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the state of São Paulo.10,11 In the Rio de Janeiro state, the blaCTX-M-15 was found in E. coli isolates associated with a dominant clone (sequence type 410).12

Despite many reports of CTX-M producing isolates in Brazilian hospitals, few studies have been conducted about the molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Thus, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae, using molecular typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in bloodstream isolates collected in the period of 2007–2008 from patients admitted to five hospitals located in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Material and methodsBacterial isolatesAs part of the Bacterial Nosocomial Infection Resistance Surveillance Network, a total of 231 consecutive non-duplicate K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae isolates originated from bloodstream infections were collected from inpatients during the period from September 2007 to September 2008, in five public tertiary care hospitals located in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All species were confirmed by using both conventional techniques and the automated Vitek System (BioMérieux, Marcy, I’Etoile, France).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and confirmation of ESBL productionThe isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility using the disk diffusion method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.13 The following antibiotic disks (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hants, England) were used: ceftazidime (CAZ), cefotaxime (CTX), cefepime (FEP), aztreonam (ATM), ciprofloxacin (CIP), gentamicin (CN), amikacin (AK), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT), ertapenem (ETP), meropenem (MEM), and imipenem (IPM). Results were interpreted according to the guidelines of the CLSI.14 Isolates showing resistance to third-generation cephalosporins were screened for ESBL activity by the double-disk synergy test (DDST) using Oxoid disks.15

PCR amplification and DNA sequencingIn isolates screened as ESBL producers, we performed Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification to determine the presence of blaCTX-M using primers and conditions previously described.16 In isolates considered positive, another PCR for blaCTX-M-15 was performed.16,17 In isolates showing resistance to carbapenems, we performed the PCR methodology for blaKPC gene detection. The PCR products were purified using the GFX™ PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and sequenced.18 Sequence analysis and alignment results were compared with sequences available from GenBank (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresisGenomic DNA analysis of K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae isolates were performed by PFGE, after digestion with XbaI (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), using the Chef-DR III System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). DNA relatedness was computationally analyzed using BioNumerics v.4.0 software (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). The banding patterns were compared by using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA), with the Dice similarity coefficient required to be >80% for the pattern to be considered as belonging to the same PFGE type.

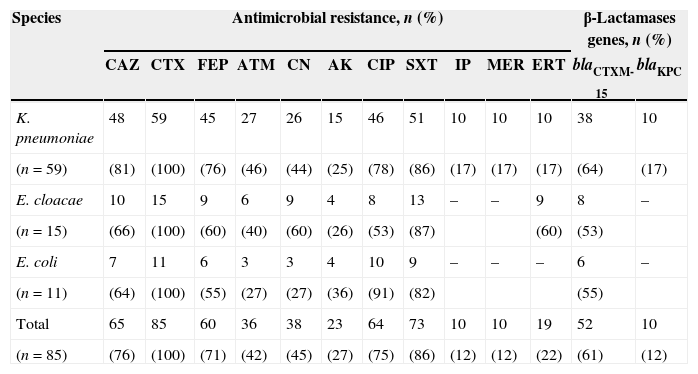

ResultsOf the 231 bloodstream isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from patients admitted to general medical wards or intensive care units, 93 isolates were screened as positive for ESBL by phenotypic test. Among ESBL producers, 85 isolates were found to carry CTX-M-type determinants (91%). The distribution of CTX-M among the species was: 59 of 121 isolates for K. pneumoniae (49%), 15 of 36 for E. cloacae (42%), and 11 of 74 for E. coli (15%). The CTX-M-15-positive isolates represented 61% of CTX-M-producers distributed among the species as follows: 64% (38/59) for K. pneumoniae, 53% (8/15) for E. cloacae, and 55% (6/11) for E. coli (Table 1).

Characteristics of the CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates.

| Species | Antimicrobial resistance, n (%) | β-Lactamases genes, n (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ | CTX | FEP | ATM | CN | AK | CIP | SXT | IP | MER | ERT | blaCTXM-15 | blaKPC | |

| K. pneumoniae | 48 | 59 | 45 | 27 | 26 | 15 | 46 | 51 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 38 | 10 |

| (n=59) | (81) | (100) | (76) | (46) | (44) | (25) | (78) | (86) | (17) | (17) | (17) | (64) | (17) |

| E. cloacae | 10 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 13 | – | – | 9 | 8 | – |

| (n=15) | (66) | (100) | (60) | (40) | (60) | (26) | (53) | (87) | (60) | (53) | |||

| E. coli | 7 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 9 | – | – | – | 6 | – |

| (n=11) | (64) | (100) | (55) | (27) | (27) | (36) | (91) | (82) | (55) | ||||

| Total | 65 | 85 | 60 | 36 | 38 | 23 | 64 | 73 | 10 | 10 | 19 | 52 | 10 |

| (n=85) | (76) | (100) | (71) | (42) | (45) | (27) | (75) | (86) | (12) | (12) | (22) | (61) | (12) |

CAZ, ceftazidme; CTX, cefotaxime; FEP, cefepime; ATM, aztreonam; CN, gentamicin; AK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazol; IP, imipenem; MER, meropenem; ERT, ertapenem; n, number of isolates; (%), percentage.

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing for CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates showed that all isolates were resistant to cefotaxime (100%), while 76%, 71%, and 42% were resistant for ceftazidme, cefepime, and aztreonam, respectively. In addition, co-resistance for amikacin (27%), gentamicin (45%), ciprofloxacin (75%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (86%) was observed. We found 10 isolates of K. pneumoniae and nine of E. cloacae showing resistance to the tested carbapenems. PCR for blaKPC gene showed that 17% (10/59) of CTX-M-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were positive and this gene was not detected in nine isolates of E. cloacae resistant to ertapenem (Table 1). In our isolates of K. pneumoniae KPC-2 type were found in four hospitals studied in 2007 and 2008. Among the KPC isolates, CTX-M-15 was observed in 80% of isolates (8/10).

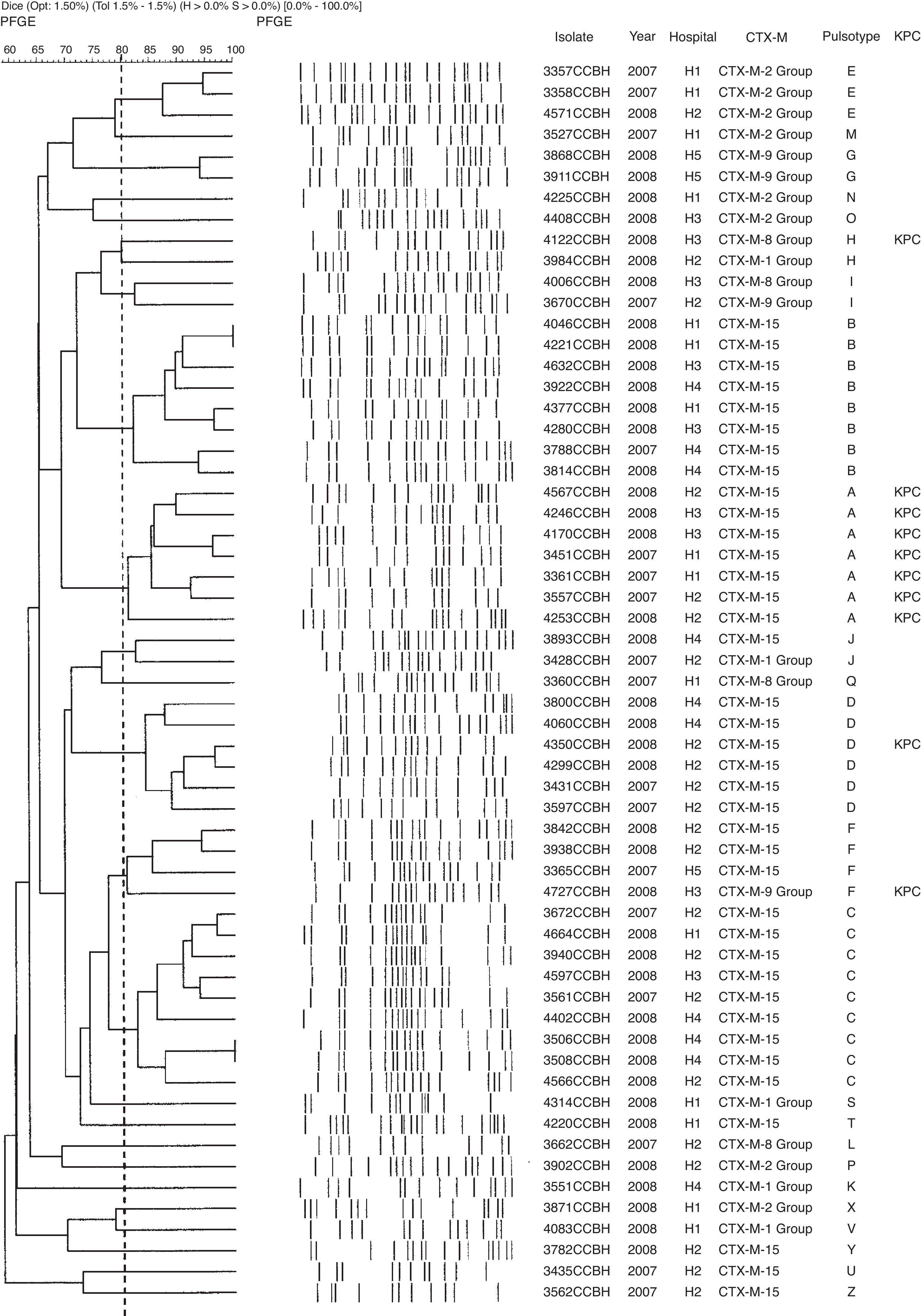

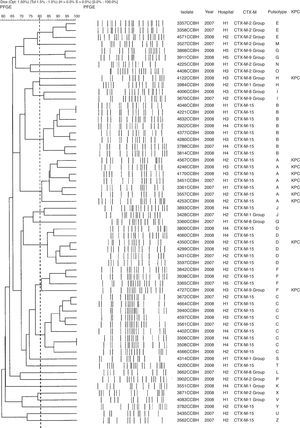

Genetic polymorphism analyses showed 24 different pulsotypes in K. pneumoniae, designated from A–Z, displaying >80% similarity within each type. Of the 59 K. pneumoniae isolates, 30 (51%) belonged to four dominant pulsotypes: A (n=7), B (n=8), C (n=9), and D (n=6). The blaCTX-M-15 was found in 10 pulsotypes (A, B, C, D, F, J, T, U, Y, and Z). All isolates of pulsotype A (n=7) and one isolate of each pulsotypes D, F, and H were KPC producers. The CTX-M-producing K. pneumoniae pulsotypes were distributed among the hospitals as showed in Table 2. Other groups of CTX-M were also found in K. pneumoniae (Fig. 1).

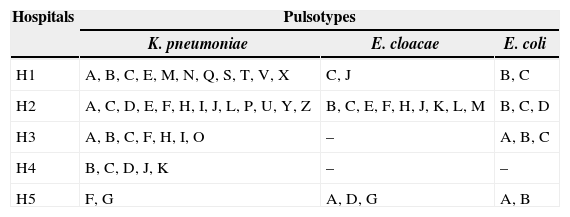

Distribution of the pulsotypes of CTX-M-producing K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae and E. coli isolates in five hospitals in Rio de Janeiro.

| Hospitals | Pulsotypes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae | E. cloacae | E. coli | |

| H1 | A, B, C, E, M, N, Q, S, T, V, X | C, J | B, C |

| H2 | A, C, D, E, F, H, I, J, L, P, U, Y, Z | B, C, E, F, H, J, K, L, M | B, C, D |

| H3 | A, B, C, F, H, I, O | – | A, B, C |

| H4 | B, C, D, J, K | – | – |

| H5 | F, G | A, D, G | A, B |

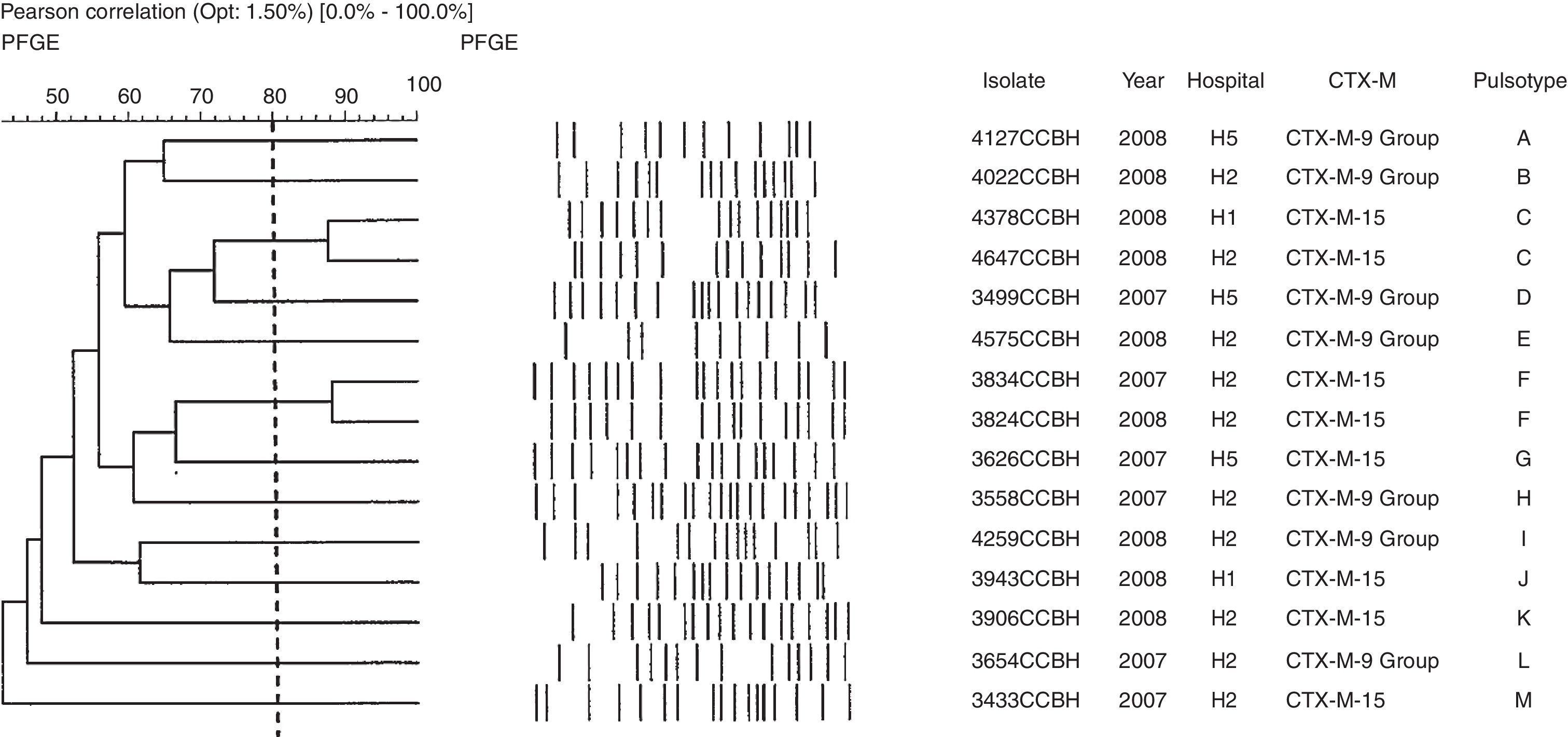

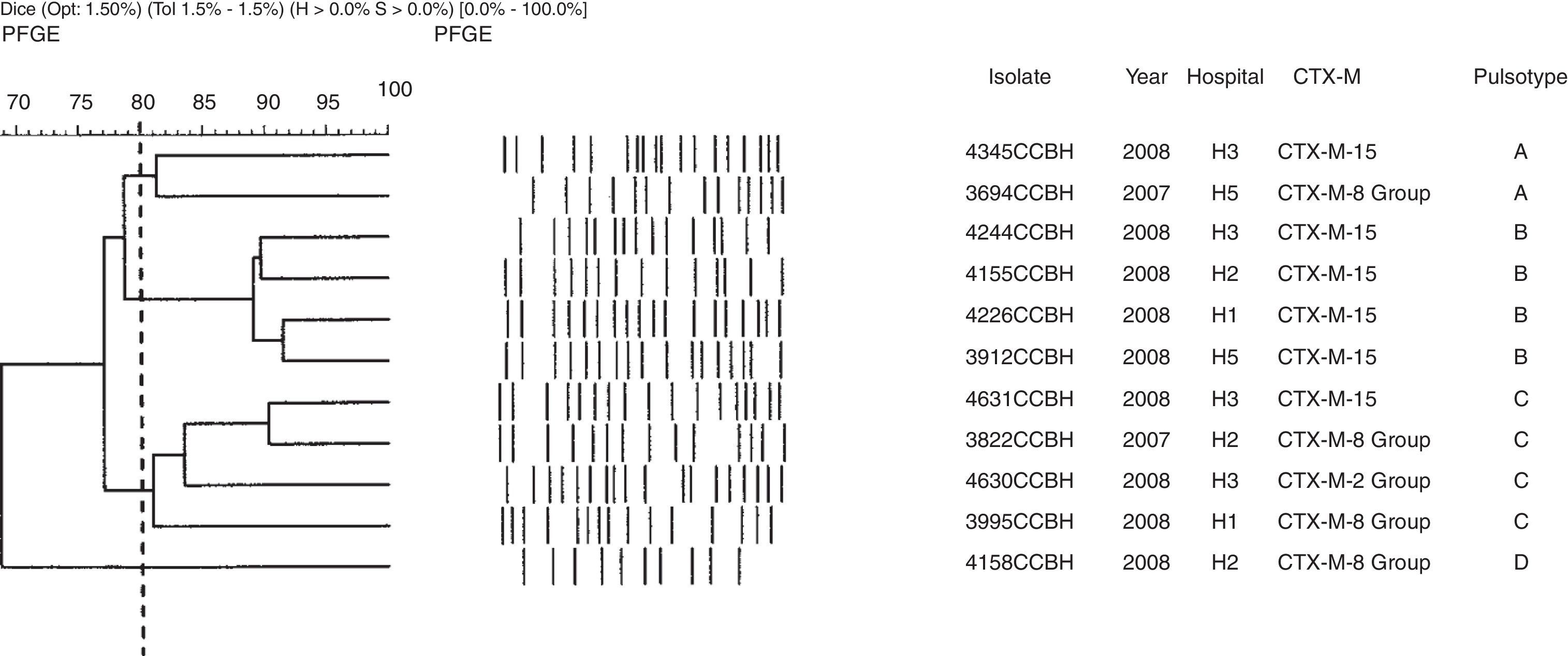

Genetic polymorphism analyses of E. cloacae showed 13 pulsotypes. The blaCTX-M-15 was found in six pulsotypes (C, F, G, J, K, and M), in the hospitals designated H1, H2, and H5. The group 9 of blaCTX-M gene was found in seven isolates of E. cloacae and in seven pulsotypes (A, B, D, E, H, I, and L) (Fig. 2). Of the four E. coli pulsotypes (A, B, C, and D) observed, eight isolates (73%) belonged to pulsotypes B (four isolates; four hospitals), and C (four isolates; three hospitals). The blaCTX-M-15 was found in six isolates, three pulsotypes (A, B, and C) and four hospitals (H1, H2, H3, and H5). The groups 2 and 8 of blaCTX-M gene also were found in E. coli (Fig. 3). The distribution of pulsotypes of E. cloacae and E. coli isolates among the hospitals was demonstrated in Table 2.

DiscussionCTX-M-producing organisms are a clinical problem worldwide,1 particularly in Latin American countries and especially in Brazil, where high endemic rates in Enterobacteriaceae isolates have been reported.8,9 In this study, we observed that the majority of the ESBL-producing isolates (91%) were characterized as CTX-M-producers, supporting the recognition of CTX-M as the most prevalent type of ESBL in the world.1K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae were the most prevalent CTX-M-producing species.

In this study, CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates had high rates of resistance to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin and gentamicin. Co-resistance to antimicrobial agents other than beta-lactams among ESBL and KPC producing isolates has been very common, imposing severe restriction on therapeutic choices for patients with such infections. Resistance to other classes of antimicrobial agents may be due to simultaneous transference of the resistance genes via plasmids and integrons.19

In this report, we analyzed the molecular epidemiology of CTX-M in five hospitals from Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). We observed the emergence of CTX-M-15 among bloodstream isolates in 2007–2008.

The predominance of the blaCTX-M-15 gene involved in different pulsotypes of K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, and E. coli is important because it is representative of the epidemiology at that time. Usually, in K. pneumoniae and E. coli, species, the CTX-M-15 has been reported as the dominant type of CTX-M in many countries causing nosocomial and community acquired infections by both clonal and polyclonal spread.2–4,20 In E. cloacae, CTX-M-15 genes have been described since 2004,21 but information about the molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-15 producing isolates in this specie is scarce.

Although in South America the CTX-M-2 has been the most prevalent type of ESBL detected,9 CTX-M-15 was reported in 2004 among fecal E. coli isolates from Peru and Bolivia,22 later Colombia,23 and recently in Argentina.24 In Brazil, the occurrence of CTX-M-15 was first reported in one E. coli clinical isolate (in 2006) from a private hospital of São Paulo State,10 and later in K. pneumoniae isolates in a teaching hospital also in the state of São Paulo with high coefficient of similarity (>86.5) among isolates, indicating a close genetic relationship.11 In Rio de Janeiro state, the blaCTX-M-15 gene was found in E. coli isolates associated both to a dominant clone (ST 410), and ST131 (two isolates), which is spread worldwide.12

The presence of KPC has already been described worldwide,25 including reports from Brazil.16,19,26,27 In our isolates, the majority of KPC producing isolates carried also the blaCTX-M-15 gene. The frequent association of CTX-M with KPC in K. pneumoniae in this and other studies suggests the acquisition of transmissible plasmids carrying blaKPC-2 gene by local endemic strains harboring the blaCTX-M-15 gene. Among the KPC producing isolates the dominant pulsotype (pulsotype A) was found, belonging to ST437, which is disseminated in five Brazilian States.19,28,29 This ST437 belonged to clonal complex (CC) 11, which is an important complex because it also includes two STs (ST258 and ST11) that have a prominent role in the spread of the blaKPC gene. The ST11 has been reported in Hungary, Spain and China2,3,30 and has also been extensively associated with CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14.6

The blaKPC gene was not detected in the nine isolates of E. cloacae resistant to ertapenem, perhaps due to other possible resistant mechanisms, such as an association between CTX-M production and porin loss that are also responsible for decreased susceptibility to carbapenem, as previously reported.31

Although more studies need to be conducted to clarify some questions, this study shows that the increased frequency of CTX-M-15 producing isolates may have been influenced by both multiple clones and/or several mobile genetic elements.

In conclusion, this study provides additional information of the epidemiological scenario of CTX-M-types among Enterobacteriaceae isolates circulating in Brazilian hospitals in 2007–2008. This data reinforce the need for continuing surveillance because this scenario may have changed over the years.

Financial supportWe thank by financial support for Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Organização Pan-Americana de Saúde (OPAS), Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank the platform Genomic for DNA sequencing do Programa de Desenvolvimento Tecnológico em Insumos para Saúde (PDTIS) do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz and all the contributing laboratories that provided isolates for this study.