Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus share a similar transmission pathway and are often diagnosed in the same patient. These patients tend to have a faster progression of hepatic fibrosis. This cross-sectional study describes the demographic features and clinical profile of human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis co-infected patients in Paraná, Southern Brazil. A total of 93 human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients attending a tertiary care academic hospital in Southern Brazil were included. Clinical, demographic and epidemiological data were evaluated. Hepatitis B virus and/or hepatitis C virus positive serology was found in 6.6% of patients. The anti-hepatitis C virus serum test was positive in 85% (79/93) of patients, and the infection was confirmed in 72% of the cases. Eighteen patients (19%) were human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B virus positive (detectable HBsAg). Among co-infected patients, there was a high frequency of drug use, and investigations for the detection of co-infection were conducted late. A low number of patients were eligible for treatment and, although the response to antiretroviral therapy was good, there was a very poor response to hepatitis therapy. Our preliminary findings indicate the need for protocols aimed at systematic investigation of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients, thus allowing for early detection and treatment of co-infected patients.

Worldwide, 350 and 180 million people are estimated to have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV), respectively. Overall, 20–30% of HCV patients and 4–10% of chronic HBV individuals are co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has improved the clinical outcomes of HIV-infected patients and decreased the rates of morbidity and mortality by reducing the incidence of opportunistic infections. According to Brazilian government data, the free availability of antiretroviral drugs to all HIV-infected patients decreased the mortality rate due to AIDS by 49% and reduced hospital admissions by 7.5 fold, confirming the efficacy of the instituted therapy.2 However, as a result of the higher life expectancy, chronic diseases caused by HBV and HCV infections, together with antiretroviral drugs hepatotoxicity, have become important causes of morbidity and mortality in HIV infected patients.3

In Brazil, the most common risk factors for HIV/HBV co-infection are sexual intercourse, especially in men who have sex with men (MSM), and intravenous drug use (IDU).4–6 The worldwide prevalence of HBV/HIV co-infection is heterogeneous and in Brazilian health service clinics, it ranges between 5.3% and 24.3%.7,8 HIV-infected patients are at a 5–6 times higher risk of becoming chronic carriers of HBV, show higher rates of reactivation, and progress more frequently to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10

In most cases, the concomitant infection with HIV and HCV is associated with percutaneous exposure, especially IDU.11 The Brazilian health services have reported HIV/HCV prevalence rates of 9.2–54.7%,7,8,12–15 HIV/HCV co-infection leads to higher HCV viral load, more intense hepatic inflammation and necrosis, and is associated with earlier progression to hepatic insufficiency and cirrhosis as compared to mono-infected patients.16,17

The prevalence of HBV and/or HCV co-infection in HIV patients varies significantly across geographic regions. The present study investigated the prevalence, epidemiological features, and clinical evolution of HBV and/or HCV and HIV co-infection cases in patients treated at an HIV referral center in Paraná State, Southern Brazil.

This is a cross-sectional study carried out in a tertiary care academic hospital; patients were prospectively included from March 2011 through March 2013. The Institutional Review Board of HC/UFPR approved the study (IRB# 2304.198/2010/08).

One hundred eight-one co-infected patients were identified by analysis of database, of these 93 patients met the study inclusion criteria: age >18 years; positive serology for HIV (anti-HIV), HBV (HBV-specific antigens and antibodies), and/or HCV (anti-HCV) registered in the respective medical record; and voluntary participation by written informed consent. Patients with incomplete medical information, children, no follow-up visit to the clinic in the last three years, and those who did not agree to participate in the study were excluded.

An epidemiological survey was carried out using a questionnaire designed to obtain information regarding educational level, sexual practices, past or present history of drug abuse, alcohol consumption, blood transfusion prior to HIV diagnosis, tattooing, and body piercing. The researchers conducted personal interviews in a private and confidential environment. The information obtained from patients’ medical records included demographic data (age, sex, race), anti-HCV result, qualitative/quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for HCV, HCV genotyping, HBV serological data (HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs), ultrasound and liver biopsy findings (fibrosis, steatosis, siderosis, cirrhosis), previous HBV or HCV treatment (treatment duration, drugs used, response to therapy), date of HIV infection, HIV viral load (last result), CD4+ T cell count (nadir and last result), and HAART use. Patients treated for chronic hepatitis C were considered to be cured if sustained virologic response was achieved six months after completion of therapy.

Data were compiled using JMP software, version 5.2.1 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2004 and analyzed by GraphPad Prism version 5.03 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were adopted, all p-values were two-tailed, and a value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

HIV/hepatitis co-infection occurred in 6.6% of the cases. HCV serology was positive in 85% (79/93) of individuals: 57 (72%) cases had qualitative PCR-confirmed infection, 12 (15%) cases were PCR negative, and 10 (13%) patients were not investigated by PCR. Eighteen patients (19%) were positive for HIV/HBV co-infection.

HCV and HBV infection occurred predominantly in male Caucasians with a low to moderate educational level. Furthermore, the majority of patients were heterosexual, with less than two sexual partners per year (61.5%), and intravenous drug users (50%) (Table 1).

Demographic, epidemiological, and laboratory characteristics of HIV/Hepatitis co-infected patients.

| Characteristics | HIV/HCVn=57(%) | HIV/HBVn=18 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 35 (61.5) | 16 (89) | 0.041 |

| Female | 22 (38.5) | 2 (11) | |

| Age (y, median) | 47 | 41 | 0.049 |

| IQR | (42–53) | (37.7–51.5) | |

| Race | 0.884 | ||

| White | 32 (56) | 12 (66.5) | |

| Afro-descendent | 15 (26.5) | 4 (22.5) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.5) | – | |

| NI | 9 (16) | 2 (11) | |

| Years of study | 0.393 | ||

| 1–3 years | 5 (9) | 1 (5) | |

| 4–7 years | 18 (31.5) | 4 (22) | |

| 8–11 years | 17 (30) | 3 (17) | |

| ≥12 years | 6 (10.5) | 3 (17) | |

| NI | 11 (19) | 7 (39) | |

| Drug use | 0.488 | ||

| Yes | 36 (56) | 8 (44.5) | |

| IV | 24 (61.5) | 4 (50) | |

| Other | 12 (38.5) | 4 (50) | |

| No | 17 (30) | 6 (33.5) | |

| NI | 8 (14) | 4 (22) | |

| Sexual behavior | 0.0016 | ||

| MSM | 2 (3.5) | 4 (22) | |

| Heterosexual | 42 (73.5) | 5 (28) | |

| Bisexual | 2 (3.5) | 3 (17) | |

| NI | 11 (19.5) | 6 (33) | |

| Number of partners | 0.054 | ||

| <2 years | 34 (59.5) | 5 (28) | |

| 2–5 years | 2 (3.5) | 3 (16.5) | |

| >5 years | 8 (14) | 3 (16.5) | |

| NI | 13 (23) | 7 (39) | |

| Hepatitis diagnosis time (y, median) | 7 | 0.030 | |

| IQR | (5–9.5) | 6 (4.5–7) | |

| Hepatitis treatment | NA | ||

| Yes | 28 (49) | 16 (89) | |

| SVR | 9 (32) | – | |

| Null response | 16 (57.5) | 4 (25) | |

| Relapse | 1 (3.5) | – | |

| Withdrew | 2 (7) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Inadequate | – | 3 (18.5) | |

| NI | – | 7 (44) | |

| No | 29 (51) | 2 (11) | |

| HIV diagnosis time (y, median) | 11 | 12 | 0.676 |

| IQR | (8–14) | (4.7–15) | |

| HIV viral load | 0.150 | ||

| Detectable | 21 (37) | 3 (17) | |

| (Median, IQR) | 668 (171–37,480) | 18,446 (1620–38,436) | |

| Undetectable | 36 (53) | 15 (83) | |

| CD4+LT value (median, IQR) | |||

| Nadir | 139 (75–265.5) | 164 (42.7–274.7) | 0.995 |

| Current | 288 (270.5–531) | 465.5 (318.3–749.3) | 0.155 |

| HAART use | 0.141 | ||

| Yes | 56 (98) | 16 (89) | |

| No | 1 (2) | 2 (11) | |

NI, not informed; IQR, interquartile range; y, years.

In general, the studied patients had a long-standing HIV infection or AIDS, with a median duration of 11 years (IQR, 8–14), and 62 patients (66%) had undetectable viral load and showed an improvement of cell immunity with a median of 143cells/mm3 and 406cells/mm3 for nadir and current CD4+ T cell count, respectively.

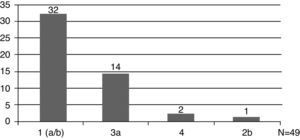

The HCV genotype was analyzed in 49 patients (49/57, 86%), and genotype 1 was the most prevalent (33/49, 67%) (Fig. 1). Hepatic disease was investigated by abdominal ultrasound in 68% (39/57,) of cases and by liver biopsy in 65% (37/57). Fibrosis was the most frequent finding in biopsies.

Twenty-eight patients received therapy with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, and out of these patients, only 33% developed sustained virologic response (SVR). However, analysis of the SVR rate among patients with distinct genotypes revealed that genotype 1 patients had the worst response to treatment, with only 23.5% SVR.

A total of 88 patients (95%) were investigated for HBV infection. The frequency of HBsAg positive patients was 20% (18/88). Only 7/88 (8%) of these individuals had single anti-HBs antibodies, and 12/88 (13%) had anti-HBs and total anti-HBc antibodies. Forty-three patients (49%) did not have any antibodies against HBV.

Twelve patients received a regimen, which included dual therapy of lamivudine and tenofovir for HBV, but three patients received only one drug – lamivudine – and another patient was not given HBV-specific therapy.

This is the first study to investigate HIV/hepatitis co-infection in Paraná. The co-infection frequency, its clinical impact, the lack of adequate anti-HCV serum test screening, and inadequate therapeutic response emphasize the need for training of health professionals in the management of co-infection cases and the necessity for rapid therapeutic strategies against this serious public health problem.

Despite the development of novel and more effective therapies, hepatic disease in co-infected patients remains complicated and costly to treat. Therefore, prevention of chronic infection should be a priority.18 However, despite the guidelines recommendation for systematic and routine laboratory investigation of co-infection, it is still not performed in referral centers where the prevalence of high-risk patients, such as IDUs, is low.

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of viral hepatitis was made after the diagnosis of HIV. This suggests a late diagnosis of hepatitis or that the infection occurred after the diagnosis of HIV. A continuous educational approach about STDs should be enforced in health care services to prevent co-infection.

It should be emphasized that the update of the Brazilian guidelines and, consequently, the recommendation to introduce HAART treatment earlier to co-infected patients was available only after 2010; until then, detection of hepatic disease in patients with a CD4+ T cell count <350cells/mm3 was not followed by specific HIV therapy. Consequently, risk factor-based screening failed to identify most individuals infected with HCV, and in patients who had positive anti-HCV serology, the confirmation of infection by PCR was not routinely performed.

The high frequency of HIV/HCV co-infection, the small number of patients eligible for treatment, and reduced clinical response observed in our study were similar to previous reports. Usually, approximately 15–45% of HCV co-infected patients have viral clearance. In this study, SVR was observed in 33% of the cases, and 20–30% of patients with persistent viremia may develop liver fibrosis, and potentially cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.19 These findings highlight the necessity for timely diagnosis and treatment as well as serious harm-reduction programs seeking to control and eliminate HCV infection and transmission among these patients.20

Many patients were only screened once for HCV infection during their follow-up, and ongoing screening was not usually performed because HIV typically has shorter latency until manifestation and is brought to clinical attention sooner than HCV. However, these patients remain at risk for liver infection, and yearly testing for HCV antibodies and liver function abnormalities in HIV-infected MSM and IDUs are both necessary and cost effective.

As previously reported, low RVS rates were observed among the patients eligible for therapy. The treatment approach is complex and requires intensive monitoring and support to achieve viral eradication. Nevertheless, HCV therapy should be provided if the potential benefits of therapy outweigh the potential risk of treatment-related toxicity. Overall, 20% of the investigated patients were HIV/HBV co-infected, and this frequency was lower than that of HCV/HIV co-infection. Nonetheless, this frequency is 20-fold higher the prevalence described in the general population of this region. In this study, we observed that some co-infected patients were in monotherapy for their hepatitis. It should be noted that, in an attempt to achieve better control of the HIV infection, the physician might have chosen not to maintain the treatment for the hepatitis co-infection. However, when the antiretroviral drugs need to be changed for any reason (i.e., side effects, HIV virological failure, or drug interactions) and even when the patient has complete HBV suppression, drugs active against HBV should be included in the new regimen.1 A total of 9% of the patients had only anti-HBc antibodies, and such serological results should be further investigated to determine if they are false-positive and to detect a “serologically silent” or occult HBV infection found in individuals with negative HBsAg but detectable serum HBV-DNA.

In conclusion, information about co-infection in developing countries, such as Brazil, is unavailable, and serological surveillance studies to determine the prevalence of HIV/Hepatitis co-infection in the HIV referral centers should be encouraged. All HIV-positive patients should be periodically screened for HCV and HBV co-infection, seeking to assess the rate and the clinical consequence of the co-infection. The significant risk of adverse effects and the high pharmacologic complexity of managing co-infected patients highlight the need for ongoing training of health professionals and more effective HBV and HCV infection-prevention strategies.

FundingThis study was supported by Fundação Araucária and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.