Management of children with HIV/AIDS is specially challenging. Age-related issues do not allow for direct transposition of adult observations to this population. CXCR4 tropism has been associated with disease progression in adults. The geno2pheno web-base is a friendly tool to predict viral tropism on envelope V3 sequences, generating a false positive rate for a CXCR4 prediction. We evaluated the association of HIV-1 tropism prediction with clinical and laboratory outcome of 73 children with HIV/AIDS in São Paulo, Brazil. The CXCR4 tropism was strongly associated with a lower (nadir) CD4 documented during follow-up (p<0.0001) and with disease severity (clinical event and/or CD4 below 200cells/mm3) at the last observation, using commonly applied clinical cutoffs, such as 10%FPRclonal (p=0.001). When variables obtained during follow-up are included, both treatment adherence and viral tropism show a significant association with disease severity. As for viremia suppression, 30% (22/73) were undetectable at the last observation, with only adherence strongly associated with suppression after adjustment. The study brings further support to the notion that antiretroviral treatment adherence is pivotal to management of HIV disease, but suggests that tropism prediction may provide an additional prognostic marker to monitor HIV disease in children.

Management of children with HIV/AIDS is specially challenging. Although antiretroviral (ARV) treatment may lead to viremia control and clinical benefit comparable to adult patients, time for treatment initiation, therapy change strategies, along with other age-related issues, pose additional challenges, adding to higher risk of ARV failure among children.1 For children with vertically-acquired infection, acute infection occurs during the neonatal period, a time characterized by exceedingly high viremia levels that decline, albeit more slowly than in adults, over the next two or more years to reach a set point. This set point tends to be higher in children, as compared to adults, and is consistent with more rapid disease progression.2–4Although the goal to eliminate HIV maternal-to-child-transmission (MTCT) is a current priority for international agencies, about 400,000 children are infected annually, and pediatric AIDS remains a major public health issue in many areas. Moreover, for patients who receive adequate care and treatment, life expectancy is extended into adulthood. A better understanding of the pathogenesis of children with HIV/AIDS is instrumental, as the clinical evolution in this population might differ from patients that acquire HIV with a mature immune system.

Over the years, various clinical and laboratory markers of disease progression have been proposed for adults and children, although the determinants for disease progression, especially in children, are unclear. The CD4+ T-lymphocyte count (CD4) and viral load (VL) are the primary markers that have been used in different studies to initiate and monitor antiretroviral therapy (ART) in clinical practice.5–9 Additional parameters could improve clinical decision-making, especially those that can predict disease progression. Viral envelope characteristics have been associated with HIV pathogenesis since the beginning of the epidemic.10 To initiate cellular infection, HIV needs to use the CD4 receptor along with a chemokine coreceptor, mostly CCR5 or CXCR4. Based on the coreceptor usage, HIV-1 variants may be classified as R5-tropic, X4-tropic or dual-tropic (DM). While most primary infections involve viruses that use CCR5 as a coreceptor, CXCR4-using viruses are often identified in adults with advanced disease and its identification has been associated with rapid progression.11–14 Viral tropism, although a phenotypic characteristic, can be predicted with genotypic methods. These tests have greater accessibility, lower cost, and shorter assay time than phenotypic methods.15,16

The identification of surrogate markers that provide clues to the clinical outcome may be useful to subsidize clinical decision. The aim of this study was to evaluate HIV tropism genotypic prediction from the first available clinical sample and its association with disease progression in a clinical cohort of children and adolescents with HIV/AIDS in São Paulo, Brazil.

Materials and methodsStudy populationThe study was offered to all parents or responsible guardians of children or adolescents in regular follow-up at the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Unit of Santa Casa Hospital, São Paulo, from 2000 to 2010. Inclusion criteria consisted of being younger than 19 years, not being pregnant and having written informed consent signed by parents or guardians, with assent from older children and adolescents. Clinical and laboratory data were obtained by Medical Record review. Since March 2000, blood samples from new patients initiating follow-up have been sent to Adolfo Lutz Institute laboratory. Of the 87 children seem at this pediatric clinic, 73 had envelope sequence and VL information. Of those, 63 had also both clinical and CD4 outcome information and for 58 of those three or more CD4 determinations (a median of eight CD4 determinations) allowed the definition of a lower (nadir) CD4 count.

The study was approved by the two institutions, Institute Adolfo Lutz (CCD-BM 20/08) and Santa Casa Hospital (ISCMSP 015/10).

Disease progression was evaluated according to three criteria:

- (i)

CD4 count (nadir) during follow-up;

- (ii)

VL at last observation;

- (iii)

a composite criteria combining CD4 and clinical disease at last observation:

- •

Asymptomatic disease (AD): children clinically asymptomatic with CD4>200cells/mm3 or

- •

Symptomatic disease (SD): children with either CD4<200cells/mm3, clinical event, defined as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classification system clinical category B or C, or death.

HIV viral RNA from plasma was isolated using QIAamp® viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Germany), according to manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA synthesis (cDNA) was performed using SuperScript III enzyme (Life Technologies, USA) and random hexamers. Cell DNA was extracted using QIAamp® viral DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Germany), according to manufacturer's instructions. A nested PCR allowed for the amplification of the C2-V3 envelope region using primers ED5, ED12, ED31 and ES8, applying previously described protocols.17–19 Purified products were sequenced in automated ABI 3100 or 3130 XL Genetic Analyzers (Applied Biosystems, USA). All sequenced chromatograms obtained were assembled with Sequencher 4.14 (GeneCodes, USA) software and manually edited, considering nucleotide ambiguities whenever a significant secondary peak (∼25%) was present in two or more chromatograms. Edited sequences were evaluated individually at websites (see below) and multiple alignments were performed using ClustalW multiple-sequence alignment software, using a reference set available in the Los Alamos HIV-1 database (www.hiv.lanl.gov) and manually edited according to their reading frame, using BioEdit software.

HIV-1 clade was screened at NCBI Genotyping and REGA HIV-1 Subtyping Tools and confirmed by phylogenetic methods, using PAUP software. Drug resistance mutations (DRM) were analyzed at Stanford HIV Database and resistance was evaluated by drug class (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NRTI] DRM, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NNRTI] DRM and protease inhibitor [PI] DRM), as well as combined resistance, such as: (i) no DRM (including polymorphisms without major loss of susceptibility to any drug); (ii) resistance (intermediate or high) to drugs of only one ARV class; (iii) resistance to drugs in two classes and; (iv) resistance to drugs in all three classical classes. Resistance to new classes (integrase inhibitors and entry inhibitors) was not evaluated.

Determination of HIV-1 viral tropismViral coreceptor tropism prediction, based on edited partial envelope sequences, was evaluated at the G2P website considering the clonal option to determine the false positive rate (FPR). The FPR is thus the probability (0–1) of a false CXCR4 assignment to a non-CXCR4 envelope sequence. These results were analyzed both as continuous and dichotomous (R5/X4) variables, using the three most widely used cutoffs (20%, 10% and 5.75%) to categorize HIV-1 as only CCR5-tropic or CXCR4-tropic.

Statistical analysesTropism prediction was evaluated with independent variables of demographic, clinical and laboratory data documented at study entry, including sex, age at collection, clinical staging, mode of transmission, VL, CD4, CDC category, and previous use of ART and viral subtype at envelope. Variables obtained during follow-up included VL, CD4, clinical events including death, adherence to ART, number of ARV regimens, DRM, and polymerase subtype. Dependent variables at outcome were:

- (i)

Clinical condition and CD4 at last observation, dichotomized at 200cells/mm3 (CDC immunological category 3 versus category 1 or 2), allowing disease severity categorization as SD or AD at last observation (all children above 5 years of age at this CD4 determination);

- (ii)

Last VL dichotomized as undetectable (aviremia)/detectable (viremia) VL.

The lower CD4 documented during follow-up (nadir CD4) was also evaluated as a marker of disease progression for patients with at least three determinations during follow-up.

To evaluate differences among proportions the Pearson Qui-square or Fisher Exact tests were used, as appropriate. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare medians and ANOVA, for multiple comparisons. Correlation of quantitative variables was performed with the Spearman test (PrismaPad) and non-parametric receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve with Stata 8.0. A logistic regression analysis included all variables with p<0.20 at univariate analysis. We analyzed the data using two multiple models for each outcome. The first was only based on the variables available at baseline (study entry), and the other considered all variables obtained during follow-up, evaluated together with those available at baseline that had a p<0.20. Logistic regression analysis was performed using the Stata 8.0 statistical software, applying a level of significance of p<0.05.

ResultsParticipant characteristicsThis longitudinal study included consenting 73 children with confirmed HIV-1 infection and one or more envelope sequences.

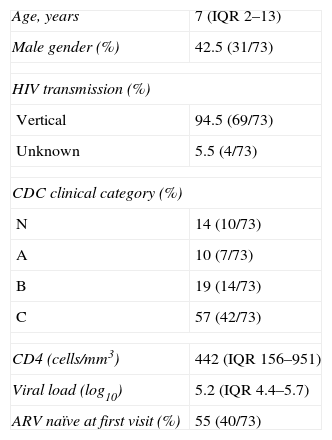

In this analysis the first available envelope sequence, obtained during follow-up, was used. The median age was seven years (ranging from two months to 18 years old) and 58% of the patients were female. HIV-1 was acquired by vertical transmission in 69 patients and in 4 cases the mode of transmission was not documented. At baseline, median VL was 5.2log10 (IQR, 4.4–5.7log10) and CD4 was 442cells/mm3 (IQR, 156–951cells/mm3), with a nadir of 149cells/mm3 (IQR, 27–395cells/mm3) during follow-up, with a median CD4 count of 491cells/mm3 (IQR, 271–954cells/mm3) at the last observation (Table 1). The patients were classified, according to CDC classification system clinical category, as N (14%), A (10%), B (19%) or C (57%). As for immunologic category, 28.7% were in category 1, 32.9% in category 2 and 35.6% in category 3, with two cases with missing data.

Baseline demographic and laboratory data of study participants.

| Age, years | 7 (IQR 2–13) |

| Male gender (%) | 42.5 (31/73) |

| HIV transmission (%) | |

| Vertical | 94.5 (69/73) |

| Unknown | 5.5 (4/73) |

| CDC clinical category (%) | |

| N | 14 (10/73) |

| A | 10 (7/73) |

| B | 19 (14/73) |

| C | 57 (42/73) |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) | 442 (IQR 156–951) |

| Viral load (log10) | 5.2 (IQR 4.4–5.7) |

| ARV naïve at first visit (%) | 55 (40/73) |

Table 1 describes baseline demographic and laboratory data of study participants; Age, at study entry, in years (median, 25th–75th interquartile range – IQR); Gender as percentage of males; HIV transmission mode, percentage of cases with documented vertical transmission mode, unknown for cases without clear mode of transmission; CDC classification clinical categories (N, A, B, C) as percentage of cases at study entry; CD4, CD4+ T lymphocytes count (median, IQR of number of cells/mm3); Viral load (median, IQR of HIV RNA copies/mL in log10); ARV naïve at first visit, percentage of patients entering the study before ARV initiation.

Most patients 40/73 (55%) were ARV naïve at collection for envelope sequencing, but all eventually initiated ART in a short period thereafter (median 19 days, [IQR, 10–71 days]). ART initiation depended on drug availability at the time of initiation, and mono-dual therapy was used by 46% of the patients as the first regimen. Part of the patients (n=33) initiated treatment before inclusion, some at other services. The median time on treatment was 7.8 years (IQR, 2.2–10.7 years). Among those starting with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the most common combination was a NNRTI (efavirenz [EFV] or nevirapine [NVP]) combined with zidovudine (ZDV) and lamivudine (3TC), used by 31% of the patients. At last documented treatment, most cases were on a lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) based HAART (45%). Patients used a median of three regimens (IQR, 1–5 regimens) during follow-up.

Patients were followed in the study for a median time of 6.1 years (IQR, 1.5–11.6 years). During follow-up, 59% (34/58) of the patients had at least one documented undetectable VL (viremia<50copies/mL) at some time during ART and 30% (22/73) were undetectable at last observation. The viremic cases had a median VL of 4.20log10 (IQR, 3.7–5log10).

Adherence was documented in 63 cases, 26 (41%) of whom had good adherence, defined by the physician's perception based on reports of missing zero to only a few pills in recent ARV regimens.

Genotype test was obtained in 68 cases, with 58% of those with one or more NRTI mutations, 51% with a NNRTI mutation and 35% with one or more major PI mutations. One class resistance was documented in 17% of the cases, two-class resistance in 21% and three-class resistance in 24%.

Genotypic tropism testing and subtypingTropism prediction was obtained in 73 cases. Using the 20%FPRclonal cutoff, 55% (40/73) were classified as R5 tropism, 67% (49/73) at 10%FPRclonal and 74% using 5.75%FPRclonal cutoff. There was a significant correlation of a lower FPRclonal with increasing age (p=0.02).

Subtype B at envelope region was documented in 53 (72.6%) cases, HIV-1 F in 16 (22%), subtype C in three (4%), with one BF recombinant. At polymerase (n=68) 74% of sequences were HIV-1 subtype B, 11% F, 4.5% C and 10.5% BF recombinants. In 15% (10/68), there was polymerase/envelope subtype discordance (B/F or F/B recombinants).

HIV-1 subtype C, all concordant in polymerase/envelope, were all classified as R5 HIV-1 infection, with a good clinical and CD4 outcome. For further analysis we categorized subtypes as HIV-1 B and non-B.

Tropism association with HIV disease progressionOverall, seven deaths occurred in this cohort. Three patients died after progressing to AIDS in the first year of life, with complications associated with the diagnosis of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (2) and intestinal cytomegalovirus. All three would be classified as R5 using the 10%FPRclonal and 2/3, if the 20%FPRclonal was used. Older children dying from AIDS-related conditions tended to have very low FPRclonal (3/4 X4, with a FPRclonal below 0.02).

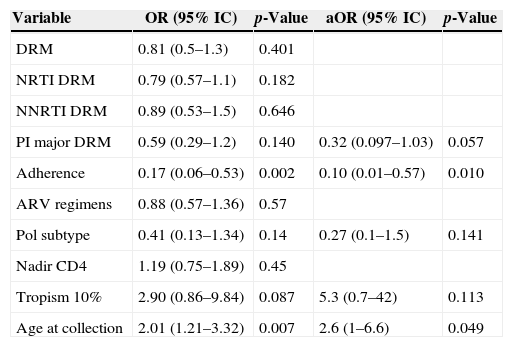

Tables 2a and 2b describe the variables associated with aviremia (VL<50copies/mL) in this cohort. Being older at the first observation was associated with virologic suppression. The R5 tropism showed no significant association (p=0.09). All variables with p<0.2 were included in multivariate analysis; older age at blood collection and R5 tropism showed a significant association. However, when all variables obtained during follow-up were evaluated in multivariate analysis, adherence showed the strongest association with viral suppression, with older age marginally associated with suppression.

Association of clinical and laboratory data with the last viral load (viremic or aviremic).

| Variable | OR (95% IC) | p-Value | aOR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.16 (1.04–1.29) | 0.006 | 1.2 (1.1–1.37) | 0.008 |

| Sex | 1.91 (0.67–5.46) | 0.23 | ||

| Clinical at entry | 0.63 (0.21–1.89) | 0.41 | ||

| Naïve at collection | 0.99 (0.36–2.69) | 0.98 | ||

| First viremia | 0.71 (0.45–1.13) | 0.15 | 1.02 (0.56–1.9) | 0.904 |

| First CD4 | 0.70 (0.37–1.30) | 0.26 | ||

| Env subtype | 1.42 (0.44–4.54) | 0.56 | ||

| Tropism 20% | 2.23 (0.78–6.38) | 0.14 | ||

| Tropism 10% | 2.90 (0.86–9.84) | 0.09 | 5 (1.3–19) | 0.03 |

| Tropism 5.75% | 2.89 (0.75–11.21) | 0.12 |

OR, Unadjusted Odds Ratio; aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; Outcome: last viral load observation as viremic or aviremic (below 50copies/mL). Age, at study entry; sex for patient gender; clinical at entry as asymptomatic (CDC clinical categories N or A) or symptomatic (CDC B or C); naïve at collection for patients entering the study before ARV initiation; first viremia and first CD4 for viral load and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count at first available determination; env subtype for HIV-1 subtype assignment for the envelope region; tropism 20%, 10%, and 5.75% for tropism prediction using three cutoffs at geno2pheno.

Association between aviremia (viral load<50copies/mL) and data from the last observation.

| Variable | OR (95% IC) | p-Value | aOR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRM | 0.81 (0.5–1.3) | 0.401 | ||

| NRTI DRM | 0.79 (0.57–1.1) | 0.182 | ||

| NNRTI DRM | 0.89 (0.53–1.5) | 0.646 | ||

| PI major DRM | 0.59 (0.29–1.2) | 0.140 | 0.32 (0.097–1.03) | 0.057 |

| Adherence | 0.17 (0.06–0.53) | 0.002 | 0.10 (0.01–0.57) | 0.010 |

| ARV regimens | 0.88 (0.57–1.36) | 0.57 | ||

| Pol subtype | 0.41 (0.13–1.34) | 0.14 | 0.27 (0.1–1.5) | 0.141 |

| Nadir CD4 | 1.19 (0.75–1.89) | 0.45 | ||

| Tropism 10% | 2.90 (0.86–9.84) | 0.087 | 5.3 (0.7–42) | 0.113 |

| Age at collection | 2.01 (1.21–3.32) | 0.007 | 2.6 (1–6.6) | 0.049 |

OR, Unadjusted Odds Ratio; aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; DRM for any drug resistance mutation that impact ARV susceptibility (according to Stanford database); NRTI DRM for nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor mutations; NNRTI DRM for non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor mutations; PI major DRM for major protease inhibitor resistance mutations; adherence as physicians perception of patient adherence to antiretroviral therapy; pol subtype: HIV-1 subtype assigned for the polymerase region; ARV regimens for the number of different ARV regimens used during observation.

Tables 2a and 2b show Odds Ratio (OR) and level of significance (p) of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. (2a) for variables available upon entering follow-up and in 2b for variables obtained during follow-up along those available upon entering that had a p<0.2. For potential co-linear variables, such as tropism prediction using different cutoffs, or antiretroviral resistance by class, the most significant variables in the univariate analysis were carried on to multivariate adjustment.

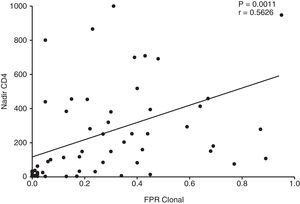

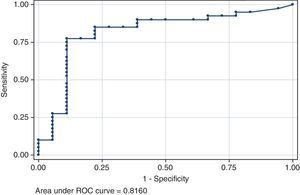

The association of viral tropism with CD4 was more noticeable. The nadir CD4 showed a strong positive correlation with the FPRclonal (p=0.0011, Fig. 1) values and R5-predicted envelope sequences had a significantly higher nadir CD4 as compared to X4 in all clinical cutoffs: 5.75%FPRclonal (p=0.0002), 10%FPRclonal (p=0.0001) and at 20%FPRclonal (p<0.0001). The area under the curve of the ROC curve of nadir CD4 for viral tropism using the 10%FPRclonal cutoff is 0.82 (95% CI 0.68–0.95) (Fig. 2). A higher nadir CD4 predicted a good clinical and CD4 outcome (p=0.001).

Using the last CD4 determination alone, above or below 200cells/mm3, we observed that children with CD4 below 200cells/mm3 had a significantly lower FPRclonal, 0.035, whereas cases with CD4 above 200 had 0.29 (p=0.0026), with a consequent higher proportion of X4 prediction. At 10%FPRclonal, only 5/16 (31%) of R5 tropism prediction is observed for cases with CD4 below 200cells/mm3, whereas those with CD4 above 200cells/mm3 were mostly R5 (79%, 44/56, p=0.001).

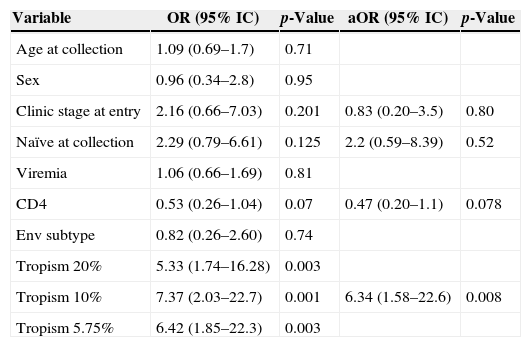

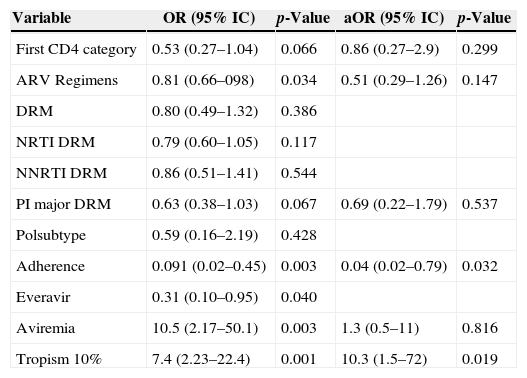

We also evaluated the association of viral tropism to disease severity (n=63) dichotomizing cases in two categories: (i) AD outcome and (ii) SD outcome. In the univariate analysis (Tables 3a and 3b), we observed that having a R5-predicted tropism, by any of the clinical cutoffs, was associated with AD. A higher CD4 (CDC category) was also marginally protective. When we analyze with other variables obtained during follow-up, better adherence, lower number of regimens and aviremia showed association with AD outcome. R5 tropism and adherence remained significantly associated with protection at multivariate analysis.

Association of information available at study entry with clinical severity.

| Variable | OR (95% IC) | p-Value | aOR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at collection | 1.09 (0.69–1.7) | 0.71 | ||

| Sex | 0.96 (0.34–2.8) | 0.95 | ||

| Clinic stage at entry | 2.16 (0.66–7.03) | 0.201 | 0.83 (0.20–3.5) | 0.80 |

| Naïve at collection | 2.29 (0.79–6.61) | 0.125 | 2.2 (0.59–8.39) | 0.52 |

| Viremia | 1.06 (0.66–1.69) | 0.81 | ||

| CD4 | 0.53 (0.26–1.04) | 0.07 | 0.47 (0.20–1.1) | 0.078 |

| Env subtype | 0.82 (0.26–2.60) | 0.74 | ||

| Tropism 20% | 5.33 (1.74–16.28) | 0.003 | ||

| Tropism 10% | 7.37 (2.03–22.7) | 0.001 | 6.34 (1.58–22.6) | 0.008 |

| Tropism 5.75% | 6.42 (1.85–22.3) | 0.003 |

OR, Unadjusted Odds Ratio; aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; Clinical Severity outcome means children with either CD4<200cells/mm3, clinical event, defined as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classification system clinical category B or C, or death. Age, at study entry; sex for patient gender; clinical at entry as asymptomatic (CDC clinical categories N or A) or symptomatic (CDC B or C); naïve at collection for patients entering the study before ARV initiation; first viremia and first CD4 for viral load and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count at first available determination; env subtype for HIV-1 subtype assignment for the envelope region; tropism 20%, 10%, 5.75% for tropism prediction using three cutoffs at geno2pheno.

Association of follow-up information and significant entry observations with clinical severity.

| Variable | OR (95% IC) | p-Value | aOR (95% IC) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First CD4 category | 0.53 (0.27–1.04) | 0.066 | 0.86 (0.27–2.9) | 0.299 |

| ARV Regimens | 0.81 (0.66–098) | 0.034 | 0.51 (0.29–1.26) | 0.147 |

| DRM | 0.80 (0.49–1.32) | 0.386 | ||

| NRTI DRM | 0.79 (0.60–1.05) | 0.117 | ||

| NNRTI DRM | 0.86 (0.51–1.41) | 0.544 | ||

| PI major DRM | 0.63 (0.38–1.03) | 0.067 | 0.69 (0.22–1.79) | 0.537 |

| Polsubtype | 0.59 (0.16–2.19) | 0.428 | ||

| Adherence | 0.091 (0.02–0.45) | 0.003 | 0.04 (0.02–0.79) | 0.032 |

| Everavir | 0.31 (0.10–0.95) | 0.040 | ||

| Aviremia | 10.5 (2.17–50.1) | 0.003 | 1.3 (0.5–11) | 0.816 |

| Tropism 10% | 7.4 (2.23–22.4) | 0.001 | 10.3 (1.5–72) | 0.019 |

OR, Unadjusted Odds Ratio; aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; DRM for any drug resistance mutation that impact ARV susceptibility (according to Stanford database); NRTI DRM for nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor mutations; NNRTI DRM for non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor mutations; PI major DRM for major protease inhibitor resistance mutations; adherence for physicians perception of patient adherence to antiretroviral therapy; pol subtype: HIV-1 subtype assigned for the polymerase region; ARV regimens for the number of different ARV regimens used during observation; Everavir for one or more undetectable viral load during follow up; Aviremia for undetectable viremia at last observation.

Tables 3a and 3b show Odds Ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI95%) and level of significance (p) of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. In 3a, associations with disease severity of variables available upon entering the study. 3b for variables obtained during follow-up among those available at entry that had a p<0.2. For potential co-linear variables, as tropism prediction using different cutoffs, or ARV resistance by class, the most significant variable in the univariate analysis were carried on to multivariable adjustment.

Some samples for tropism determination were available only near the time of the last observation. The median follow-up time after sample collection used in tropism prediction was 1.2 years (IQR, 6 days to 5.4 years). This period was similar between disease severity (p=0.7) or aviremia (p=0.9) outcome categories. However, if only children with more than one year of observation after envelope analysis were included (n=40), still a significantly lower FPR (median 0.035 IQR 0.015–0.215) is observed among those with severe clinical progression, whereas those with AD disease had a higher FPR (0.37, IQR 0.16–0.47, p=0.0015). Using the 10%FPRclonal, 10/16 with X4 predicted tropism had severe disease as compared to 3/24 with R5 predicted virus (p=0.003). The difference for viremia outcome was not significant (p=0.6).

DiscussionThe main purpose of this study was to document clinical and laboratory evolution of this cohort to evaluate if tropism determination can be useful as a marker of disease progression. For this purpose, a longitudinal follow-up of HIV-1-infected children and adolescents was carried out for over 10 years, documenting known predictors of disease progression, such as CD4 counts and adherence to treatment. One major limitation of the study is the fact that tropism determination was not performed at study entry, but sometime during follow-up, with some cases determined at the sample available near last observation. Therefore, the study can only suggest potential associations, and cannot claim that the predicted tropism determined the outcome evaluated. Also, as in other longitudinal studies in clinical settings, different factors, such as assiduity of patients, parents or guardians, proper collection and storage of the samples, documentation of clinical and laboratory data throughout the follow-up impact data collection, and missing data compromise a robust support to our findings. Although clinical trials provide a stronger basis for the development of cohort studies, the ability to grasp real world dynamics makes clinical setting observations also relevant.

Brazil has the largest pediatric population with HIV/AIDS with public access to both monitoring tools, as well as ART. Little work, however, is available on the long-term evaluation of these patients, some already initiating follow-up in adult services.

Patients in this study were followed up at a single clinical site in São Paulo, the largest city in South America. The service studied is not a specific reference center for AIDS or for infected pregnant women and therefore receives sick children that end up finding their HIV diagnosis during the evaluation at entry. Most children observed without ART at entry were brought to the service due to some clinical condition and initiated ARV shortly after this initial observation. This might have caused an inclusion bias toward more severe cases. Another issue is the fact that the service cares for patients without insurance and therefore includes a significant proportion of children from lower income strata. However, the population of the study had some degree of homogeneity, such as access to free ARV, socio cultural background and the fact that all were treated by the same clinical team, diminishing the variability in clinical management. Because of limited numbers of infected children and of mothers with relevant data, we were unable to investigate effects of other factors possibly associated with disease progression in vertically infected children, such as maternal ART use and maternal VL.

Children in clinical services are followed based on clinical condition, routine laboratory workup, and two major HIV-related prognostic markers, CD4 and VL. Although clinical evolution will be influenced by different biological, socio cultural and access to health-related issues, it is conceivable that certain viral characteristics may influence this outcome. Viral tropism has been suggested to be an additional marker of disease severity in adults.13

Although viral tropism is more properly evaluated using phenotypic assays, genotypic methods allow for a reasonable prediction, and have been increasingly used. Moreover, it was considered sufficient by the European Consensus Group to define tropism for the usage of CCR5 antagonists.14 In our study, we did not try to evaluate the tropism assay itself, but rather correlate the genotypic prediction with the actual clinical and laboratory outcomes of these patients. To that end, we analyzed envelope sequences at the geno2pheno website, a commonly used resource that provides a FPR for the probability of misclassifying a sequence as X4. Therefore, the lower the FPR, the lower the chance of false X4 classifications. As different clinical cutoffs have been used, we evaluated our dataset with the three most commonly used cutoffs.

This study showed a relatively high proportion of X4-predicted variants, 45% if a more conservative (20%FPRclonal) cutoff is used. Some previous studies reported similar prevalence in chronically infected children.20,21 One study with HIV-1 subtype C infected children, observed a lower presence of X4,22 similar to a study in Uganda with different subtypes,23 whereas others found a higher X4 prevalence.24 The differences in study design, population, age of participants, tropism definition and viral subtype may all contribute to these discrepancies. Clade C cases are considered to be preferentially R5 isolates, and in the small subgroup of clade C infection in our study we also found only R5-predicted variants.

There was a significant correlation between a lower FPR and older age in our population. Other studies20,25 also found that correlation and that tendency is in accordance with most of the evidence in adults that suggests the emergence of X4 variants later, as the disease progresses.12,26 In adults, after a mostly R5 infection, about 50% of HIV infected patients evolve to X4 tropic variants later in disease.13

Suppression of viremia is the main goal of HAART. At last observation, only 30% (22/73) of the patients achieved aviremia. This figure is not unusual for children initiating therapy before the HAART era, as is the case of many of these patients. Response rates are better for children initiating HAART with new regimens (data not shown). From the data available upon entering follow-up, being older and having a R5 virus was associated with virologic suppression in multivariate analysis (Tables 2a and 2b). However, the association of R5 with viral suppression is weak and not sustained when variables obtained during follow-up are included. When follow-up information is considered, the association of aviremia with age becomes less striking and adherence is the only strong predictor of aviremia. It is well known that a good adherence to ART is the central determinant of viral suppression and long-term disease-free survival. This is a difficult goal, particularly in very young children who rely on parents or caregivers to administer drugs and in adolescents, who are more likely than younger children either to report poor adherence themselves or to have it reported by caregivers and/or health professionals.27

The association of age with viremia suppression may be due to an easier adaptation of older children to ARV and to the bimodal nature of HIV disease in children, as pointed out by Puthanakit et al.28 in their study of treatment initiation in older children. Therefore, children who do not present clinical disease early after birth might already represent a population of better clinical outcome. Similarly, early deaths in the first year may represent either more aggressive disease or cases that reached the service at an advance stage, in which clinical intervention was of limited impact.

We did not find an association between DRM and viral suppression. It was not the objective of this paper to evaluate this issue, and resistance was considered here as one of the possible variables observed during follow-up that should be used in adjusting the multivariate analysis. The resistance profile and viral diversity of pol gene in this population have been previously published.29,30 The lack of correlation of DRM with clinical severity or viremia is possibly due to the fact that DRM is generally absent in samples from patients with adequate adherence, aviremic cases, as well as from viremic, poorly controlled, low adherence patients, as only those submitted to sufficient drug exposure would develop genetic mutations. Nevertheless, the genotypic test was helpful in guiding salvage therapy in many patients (data not shown).

Contrary to viral suppression, CD4 levels, as well as a composite outcome combining both CD4 and clinical condition, showed a strong and independent association with viral tropism. Entry CD4 (CDC category) showed a tendency in predicting a less severe outcome (p=0.08). However, viral tropism, specially using the 10%FPRclonal cutoff shows an independent, strong association with AD (Tables 2a and 2b) when only information available at the study entry is considered. When follow-up information is included, ARV adherence and R5 viral tropism are both significantly associated to AD. We also found a strong, significant correlation between FPR and CD4 nadir values (Fig. 1). There is evidence that immunologic deterioration in HIV-1–infected children precedes the viral phenotypic switch from R5 to X4 variants31 and that the presence of X4 variants is linked with faster progression to AIDS, a rapid fall in CD4 count26 and a lower CD4 nadir. This association of viral tropism with CD4, but not with viremia control, has been observed in some studies with adult patients,13 and we and others32,33 have found an association of a lower geno2pheno FPR with CD4 depletion in adults.

Since some of our cases had insufficient follow-up time after tropism determination it is not possible to exclude the possibility that the predicted tropism was secondary to clinical deterioration. The use of tropism prediction information, in a clinical setting context, may assist pediatricians in planning a more aggressive intervention in cases with more severe prognosis, maximizing resources available for populations with increased risk of disease progression. Current Brazilian treatment guidelines indicate treatment for children with clinical disease, VL above 100,000copies/mL or CD4 below 25%. Although the efforts in improving adherence are a cornerstone of treatment success, information on viral tropism, along with other prognostic markers, could be useful to support clinical decision.

In conclusion, our study documented for the first time a strong predictive association, independent from other available markers, that a high FPR, predicting a CCR5 coreceptor usage, is protective in children and is related to a better immunological (CD4 level) and clinical outcome.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by Unesco-Brazilian AIDS Program CSV 092/06 and FAPESP 2011/21958-2.