The main objective of this work is to describe the formation of the Transition Adolescent Clinic (TAC) and understand the process of transitioning adolescents with HIV/AIDS from pediatric to adult care, from the vantage point of individuals subjected to this process. A qualitative method and an intentional sample selected by criteria were adopted for this investigation, which was conducted in São Paulo, Brazil. An in-depth semi-structured interview was conducted with sixteen HIV-infected adolescents who had been part of a transitioning protocol. Adolescents expressed the need for more time to become adapted in the transition process. Having grown up under the care of a team of health care providers made many participants have reluctance toward transitioning. Concerns in moving away from their pediatricians and feelings of disruption, abandonment, or rejection were mentioned. Participants also expressed confidence in the pediatric team. At the same time they showed interest in the new team and expected to have close relationships with them. They also ask to have previous contacts with the adult health care team before the transition. Their talks suggest that they require slightly more time, not the time measured in days or months, but the time measured by constitutive experiences capable of building an expectation of future. This study examines the way in which the adolescents feel, and help to transform the health care transition model used at a public university. Listening to the adolescents’ voices is crucial to a better understanding of their needs. They are those who can help the professionals reaching alternatives for a smooth and successful health care transition.

Globally, there is increased health care burden of perinatally-infected human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adolescents who survive into adulthood. The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), alongside various prophylactic measures, has decreased morbidity and mortality rates in this group.1 The majority of these patients receive their medical care in a pediatric or adolescent medical setting.

The transition into adulthood is a critical stage of human development, during which young individuals leave adolescence behind and take on new roles and responsibilities.2

Although these changes provide opportunities for positive growth experiences, they are accompanied by new vulnerabilities.

The World Health Organization defines adolescence between 10 and 19 years of age, beginning at the onset of puberty.3 Although the majority age is 18 years in most of countries, reaching this age does not ensure acquisition of adult behavior.

Health care transition (HCT) is defined as the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults with special health care needs from child-centered to adult-centered health care.4 For many adolescents, this transition is disorganized and results in both impaired adherence to treatment and loss of consistent health care.5

HIV-infected young people between birth and 24 years of age are considered a developmentally diverse group.6 Adolescents with HIV may have experienced several psychosocial stressors such as stigma, parental illness and loss, that can make HCT an even more complex process.7 It is important that young people continue to receive appropriate care throughout and following the transition from pediatric to adult services.

Previous studies have shown several obstacles to transition, including a lack of communication between pediatric and adult providers,8 adult services that are not equipped to meet the needs of adolescents, and differences in pediatric and adult health care philosophies (i.e., the family-focused approach versus the responsible self-care focused individual). In addition, the adolescent's emerging need for independence and the family's need to ‘let go’9 are challenges faced by parents, adolescents, and health care providers.

It has been generally agreed that HCT for adolescents with chronic illnesses is a process that starts with a preparation program in the pediatric setting, followed by active transfer strategies, and finally, a period of consolidation and evaluation in the adult setting.4 At the present time, there is no evidence of a superior model for this transition in terms of patient satisfaction, cost effectiveness, or medium and long-term outcomes.10

In this article, we present the experiences of the HCT of a group of perinatally HIV-infected adolescents, whose voices we identify as crucial to a better understanding of their needs.

ObjectivesThe purposes of this study were to describe the implementation of the Transition Adolescent Clinic (TAC) and identify the needs, feelings, and experiences of HIV-infected adolescents included in an HCT program.

Study settingThe Transition Adolescent Clinic (TAC)Since 2007, the Transition Adolescent Clinic (TAC) is a component of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases in the Department of Pediatrics that follows perinatally HIV-infected adolescents older than 16 years of age. This special clinic was developed after a series of failures in previous attempts of transitioning these adolescents to an adult-centered clinic at the age of 18 years. Therefore, the aim of TAC was to facilitate the transition of this vulnerable population from pediatric to adult care. The TAC team is interdisciplinary and includes five physicians (four pediatricians and one adult infectious disease physician), two pediatric nurse practitioners, one social worker, and one psychologist. This clinic is located at the same facility as the Pediatric AIDS Unit, and when the adolescents reach 16 years of age, they step into a transitioning program. This follows a model based on the perspective that both a multidisciplinary team and a good interaction between the pediatric and adult services are essential to a successful HCT. Upon discovering that a protocol for this issue was non-existent at the time,4 the TAC team developed the three steps of a transitioning protocol described as the following:

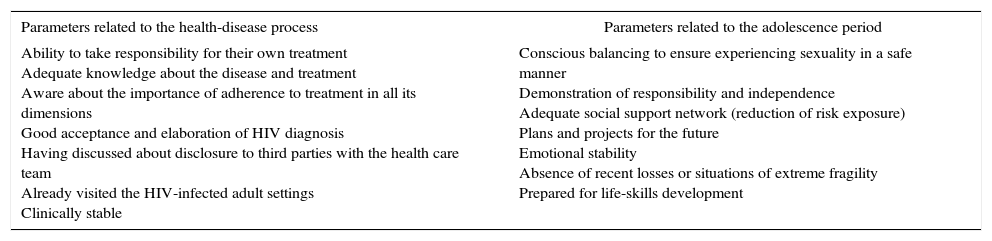

Step 1: When adolescents reach 16 years of age, the pediatricians begin the discussions with them regarding the transition process. During this period, the readiness to transition is evaluated through specific parameters, by both a pediatrician and a psychologist4 (Table 1).

Table 1.Evaluation of readiness to transition: parameters related to the health-disease process and to the adolescence period.

Parameters related to the health-disease process Parameters related to the adolescence period Ability to take responsibility for their own treatment

Adequate knowledge about the disease and treatment

Aware about the importance of adherence to treatment in all its dimensions

Good acceptance and elaboration of HIV diagnosis

Having discussed about disclosure to third parties with the health care team

Already visited the HIV-infected adult settings

Clinically stableConscious balancing to ensure experiencing sexuality in a safe manner

Demonstration of responsibility and independence

Adequate social support network (reduction of risk exposure)

Plans and projects for the future

Emotional stability

Absence of recent losses or situations of extreme fragility

Prepared for life-skills developmentStep 2: Adolescents and youths (18 years or older) meet the adult infectious diseases physician formally for the first time at the TAC. They begin to have routine clinic appointments at the TAC, conducted by the adult infectious disease physician. One pediatrician remains responsible to discuss the progress of the transition process with the adult infectious disease physician.

Step 3: Adolescents and youths start having the appointments at the adult infectious disease clinic, with two to three extra appointments at the TAC during the following 12 months, to detect barriers to transition that continue to exist. Discussions are undertaken involving the TAC team for closing the transition process.

Although there are some steps indicated by age, the overall formal transition process is not based on the patient's chronological age, but on the level of maturity and preparedness of the young patient, which can be assessed by specific parameters previously described.4

This transition program is delivered at the local level, although it is supported by a policy establishing a national standard for care regarding the issue.

MethodsIn-depth interviews, using semi-structured interview scripts, were conducted with 16 HIV-infected adolescents and youths (ages 16–25 years) who were followed at the Division of Pediatric AIDS at Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil. All interviews (lasting 30–45min) were conducted between November 2010 and April 2011 by a single member of the research team and were audio-taped and transcribed. The verbatim transcripts were independently analyzed by two members of the research team, using content analysis. Discrepancies were discussed between an independent reviewer and the two research team analysts until a consensus was reached.

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil. Informed consent, parental consent, and informed assent were obtained as appropriate.

Data analysisThe first phase of data analysis consisted of free-floating readings of the interviews, so that the researchers would be able to familiarize themselves with the material. The reviewing of transcripts was facilitated through use of NVivo 9 qualitative software (QRS International, 2011). For emerging concepts and themes, the first and second authors coded the transcripts independently, using a standard definition for each theme derived from the data. Disagreements in coding required adjustments until both coders agreed on all codes through an iterative process. Interviews were performed until no new information was being elicited from successive interviews (considered as theoretical saturation).11

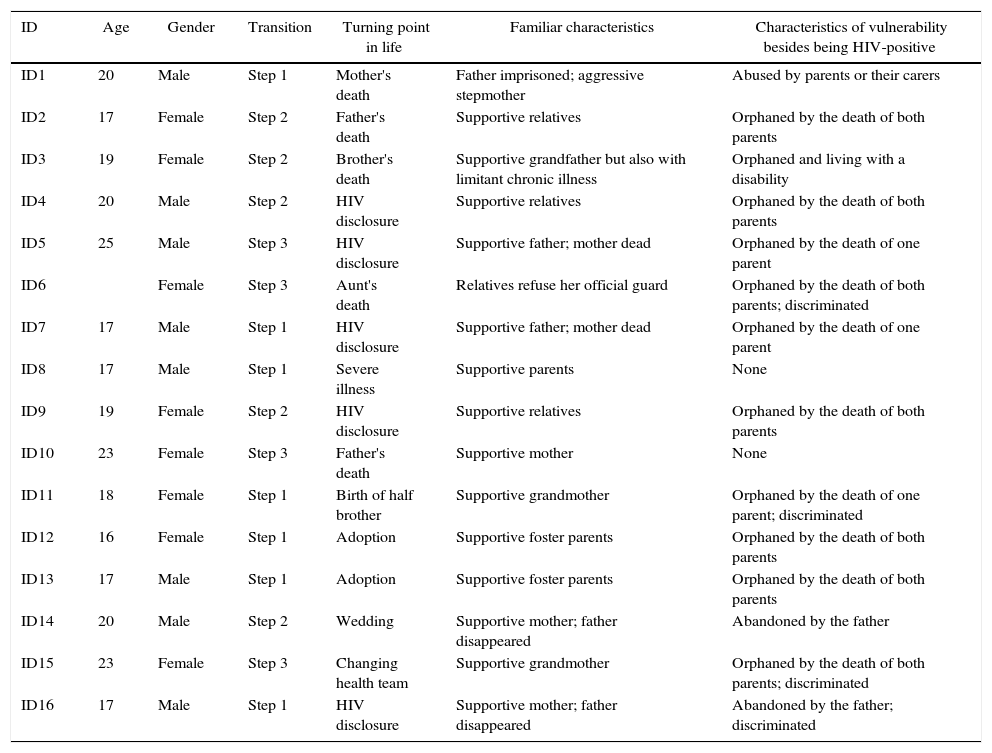

ResultsDemographicsThe number of patients included in the transition program ranged from two to four per year, retrospectively, over the previous 4 years. From 120 HIV-infected adolescents being followed in a regular basis, 16 participants were interviewed: six that were at Step 1 of the transition program, six at Step 2, and four at Step 3. Half of participants were female (n=8; 50%) and 69% white (n=11), with a median age of 17 years (Table 2).

Biopsychosocial characteristics of study population.

| ID | Age | Gender | Transition | Turning point in life | Familiar characteristics | Characteristics of vulnerability besides being HIV-positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID1 | 20 | Male | Step 1 | Mother's death | Father imprisoned; aggressive stepmother | Abused by parents or their carers |

| ID2 | 17 | Female | Step 2 | Father's death | Supportive relatives | Orphaned by the death of both parents |

| ID3 | 19 | Female | Step 2 | Brother's death | Supportive grandfather but also with limitant chronic illness | Orphaned and living with a disability |

| ID4 | 20 | Male | Step 2 | HIV disclosure | Supportive relatives | Orphaned by the death of both parents |

| ID5 | 25 | Male | Step 3 | HIV disclosure | Supportive father; mother dead | Orphaned by the death of one parent |

| ID6 | Female | Step 3 | Aunt's death | Relatives refuse her official guard | Orphaned by the death of both parents; discriminated | |

| ID7 | 17 | Male | Step 1 | HIV disclosure | Supportive father; mother dead | Orphaned by the death of one parent |

| ID8 | 17 | Male | Step 1 | Severe illness | Supportive parents | None |

| ID9 | 19 | Female | Step 2 | HIV disclosure | Supportive relatives | Orphaned by the death of both parents |

| ID10 | 23 | Female | Step 3 | Father's death | Supportive mother | None |

| ID11 | 18 | Female | Step 1 | Birth of half brother | Supportive grandmother | Orphaned by the death of one parent; discriminated |

| ID12 | 16 | Female | Step 1 | Adoption | Supportive foster parents | Orphaned by the death of both parents |

| ID13 | 17 | Male | Step 1 | Adoption | Supportive foster parents | Orphaned by the death of both parents |

| ID14 | 20 | Male | Step 2 | Wedding | Supportive mother; father disappeared | Abandoned by the father |

| ID15 | 23 | Female | Step 3 | Changing health team | Supportive grandmother | Orphaned by the death of both parents; discriminated |

| ID16 | 17 | Male | Step 1 | HIV disclosure | Supportive mother; father disappeared | Abandoned by the father; discriminated |

We identified the following categories of themes, organized by phase of experience (i.e., steps in the transition program). Some themes repeatedly emerged from adolescents at different steps of the transition program.

Turning points in their lives and how they handled changes in lifestyleSome decisive events in their life history were easily identified by the adolescents, including events such as loss of relatives, HIV disclosure, hospitalizations, and adoption. Such moments might have had some impact on how the adolescents dealt with changes and transformations in their lives, including the transition in health care. The importance of having support of family or friends was noted to be remarkable. ID8: “After I was admitted for a surgery I had a big change…I began to better accept my problem…what I had…my family…it was so important and gave me so much support…I’m still alive, fighting to live! (Male, 17 years, Step 1). ID1: “…When I was with my mother I received visits…my aunts used to see me…I was very happy there…then, when my mother died, I went to live with my father and I had no more visits…” (Male, 20 years, Step 2).

For some participants, these moments were experienced with sadness, anger, and feelings of abandonment. ID6: “…after she died nobody wanted to be my legal guardian, and since that time I was emancipated…I started getting very rebellious…I did not want to do anything, even go to school…I did not want to stay at home because it reminded me (of the loss of the relative)”(Female, 20 years, Step 3).

Two adolescents (ID12 and ID13) who were raised by foster parents reported the adoption event with enthusiasm and joy. ID13: “Oh, I think it (the turning point) was when I was adopted…I was in that institution…so, I was adopted, it was good… my life changed, you know? You have a mother…it makes a difference!”(Male, 17 years, Step 1).

One participant (ID5) had a very bad experience with disclosure of his HIV status when he was 11 years old. He was by himself when he found out about his HIV seropositivity, and he felt lonely and became extremely rebellious. Then, he became depressed and stopped his treatment several times. After a few years, he was one of those who had a great deal of difficulty with the transition process.

Other adolescents reported that the changes enabled them to grow and mature. ID 11: “I try to go on… it's not difficult for me…I manage” (Female, 18 years, Step1) ID8: “I face the changes always in a positive way…I feel ready for both problems or good things…I’m supposed to handle it” (Male, 17 years, Step 1).

The bond between these adolescents and the pediatric team are characteristic of family ties. The environment is perceived as warm, welcoming, and one that enhances the quality of interpersonal relationships. From the perspective of adolescents, care goes beyond the disease. The professionals are part of their history and are interested in their daily lives, reinforcing a sense of security and confidence. On the other hand, the fact of having grown up with this health care team makes them reluctant to face the transition, as it could bring the threat of disruption of important emotional connections. ID8: “I grew up close to you (the health team)…you are like my mother, another family…you have always been welcoming” (Male, 17 years, Step 1). ID10: “I was always treated as a daughter here…”(Female, 23 years, Step 3).

As the adolescents participating in the study were at various stages of the transition process, they made comments reflecting very different experiences. Concerns in moving away from their pediatricians and feelings of disruption, abandonment, or rejection were frequently mentioned. Others used recurring words suggesting feelings of denial and insecurity, as they were unprepared to address their own health care needs. Findings also showed moments of expectation or resilience. ID5: “Oh…there (the adult care) is bad, right? I was used to coming here…I did not want to go there, I did not go… I did not go…” (Step 3, treatment interruption during transition). (Male, 25 years, Step 3) ID13: “Then you suddenly change…and be afraid of the different…of not being prepared for changing.” (Male, 17 years, Step 1) ID2: “I’m not prepared…not yet…ah, I do not know…I never went there, I’m not ready to do so”. (Female, 19 years, Step2) ID12:” It is because I want to stay here a little bit longer…then I will start to come alone, not with my mother…” (Female, 16 years, Step 1)

On the other hand, there were testimonies showing compliance or interest in changing. ID8: “… and I said, oh! No problem… I can deal with changes…”(Male, 17 years, Step 1). ID7: “It's normal, I’m older, I have to stay right there… it's weird to be among children.” (Male, 17 years, Step 1).

Beliefs regarding the adult care were mostly loaded with negative attributes. The environment was described as unwelcoming, with rigid and hurried professionals who focus only on the disease. ID8: “I just think they don’t have that much affection as you do with patients, the thing is more drought, more serious…” (Male, 17 years, Step 1). ID16: “I don’t mean they are bad doctors, but they don’t care as you do, they are in a hurry…let's go…let's go…” (Male, 17 years, Step 1)

The adolescents expressed the need for more time to become adapted and involved in the transition process. Having grown up under the care of a team of health care providers made many participants to be reluctant toward transitioning. ID1: “You should go slowly, right?… so that you get, you know, to learn more (about the new health team)…” (Male, 19 years, Step 1). ID15: “…I’ve been always treated as a daughter over here; it was not nice to go there” (Female, 23 years, Step 3). ID4: “I think (the transition should be) after 25 years old, you know, the age that you will have more responsibility, when you go after your own stuff, right?” (Male, 20 years, Step 2).

Participants also expressed great confidence in the pediatric team. At the same time they showed interest in the new team and expected to have close relationships with them. ID1: “…sometimes I think …when I want to talk to someone…to whom am I going to talk? who will give me the attention as I have here…you know, these sort of conversations that we have had so far?” (Male, 20 years, Step 1).

They commented on the fact that the healthcare team should know the professionals who will be following them. The adolescents expect them to be gentle and open to their needs. ID15: “I would not think twice to be treated back here…because this is a welcoming place…in every sense, it's not only professional. You feel yourself loved, so… to change to another place… you have to find someone else that makes you feel loved too.” (Female, 23 years, Step 3).

They also ask to have previous contacts with the adult health care team before the transition. ID11: “I believe we should know the other team first, this would bring more security…” (Female, 18 years, Step 1) ID13: “First I need to know more about there, how is the service… how it works…see the place, meet the physicians.” (Male, 17years, Step1)

The present study provides rich data about the experience of perinatally HIV-infected adolescents at different phases of the transition process. It presents the implementation of the TAC and examines the way in which the adolescents feel, want to shape and help to transform, through their voices, the health care transition model used at a public university.

Despite the development of a transition program, the adolescents still faced barriers to this process and revealed a great variability in experiences.

They started showing us that there was something that was not working. There was a sort of “misunderstanding” in the way the health care team was dealing with this moment in their lives. This fact was complicating the patients’ adherence to treatment and follow-up. A previous study has shown that the presence of anxiety in this population is significantly related to nonadherence.12 Also, a recent study has shown that almost 20% of HIV-infected 21-year-olds had loss to follow-up (LTFU) in the year after turning 22 years. Receiving care at an adult instead of a pediatric HIV clinic was associated to LTFU.13

We listened to their concerns and rethought the transition process, as other authors from several parts of the world have started doing as well.4 Their talks suggested that they require slightly more time, not the time measured in days or months, but the time measured by constitutive experiences capable of building an expectation of future. The time for transition has nothing to do with chronological age limits. Building life plans and developing a clear understanding of their destination is not easy at the beginning of the transition process. Sometimes it is too painful to think about the future. The place in society that awaits them is not exactly welcoming. No job is guaranteed, no position is safe, and no expertise is lasting useful. Consistent discussions are needed before the transition to allow these young people to manage several issues independently. Also, adult-oriented providers have to be prepared to receive patients with childhood-onset or -acquired conditions and dealing with their particularities.

The present work permitted the opening of collective spaces for reflection, analysis, and exchange of knowledge among professionals and, above all, for interaction and listening to the demands of the participants. How to conduct the transition process in health care? How it is or can it be? How it should or should not develop? When should be process begin? Many of these questions cannot produce cognitive certainty or definitive answers. Such questions will necessarily give rise to further debate. Recently, other protocols of transition were described for HIV-infected adolescents.14,15 Life transitions are always challenging. They are inevitable and necessary, but how they occur might result in more or less suffering. The hierarchy of values we have seen in the current model of care emphasizes the technological aspects rather than its humanistic components. Listening to the adolescents’ voices is crucial to a better understanding of their needs. There are those who can help the professionals reaching alternatives for a smooth and successful health care transition.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the members of the TAC team who shared their time and experiences as part of the research process (Tenori S, MD; Gouvea AFB, MD; do Carmo FB, MD; Beltrão SV, MD; Rufino AM, nurse; de Jesus RM, nurse; Juliana Maria Figueiredo de Souza, social worker). We are grateful to the adolescents who shared their life experiences with us. Supported by a grant from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil (FAPESP # 10/15463-8).