Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a global health emergency. The clinical course of COVID-19 in children is mild in most of the cases, but multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is recognized as a potential life-threatening complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Acute abdomen as a presentation of COVID-19 is rare, and its correlation to COVID-19 features and prognosis remains undetermined. Herein, we describe a case of appendicitis in a child with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and subsequent SARS-CoV-2 identification in appendix tissue.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a global health emergency. Patients with COVID-19 may present with variable clinical features, involving pulmonary, gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular symptoms.1 The clinical course of COVID-19 is usually mild in children. However, some children can become critically ill and present a clinical condition termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).2 Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement appears to be the main pattern of clinical presentation in MIS-C and is seen in 92% of patients. Its clinical features share similarities with many other infectious and inflammatory diseases seen in children, such as Kawasaki disease (KD), toxic shock syndrome and macrophage activating syndrome.2,5 Nonetheless, acute abdomen as a presentation of COVID-19 is rare, and its correlation with COVID-19 features and prognosis remains undetermined.1 In this context, we report the case of a patient hospitalized in São Paulo, Brazil, for complicated appendicitis, with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and subsequent identification of SARS-CoV-2 by immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR in the appendix tissue.

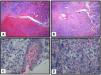

Case presentationA nine-year-old, previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of periumbilical abdominal pain and watery diarrhea, vomiting, evolving with a daily fever of up to 38 °C and progressive worsening of the pain. The patient was discharged home with analgesics. The next day, he was hospitalized due to worsening of previous symptoms and antibiotics were started. He was transferred to our service for diagnostic procedures and surgical evaluation due to the hypothesis of appendicitis. Dysuria and oliguria were also described. Upon admission the patient was in good general condition, hemodynamically stable, with abdominal pain and signs of peritonitis. After surgical evaluation, fasting, antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole) and maintenance fluid were prescribed. The ultrasound examination was inconclusive. The hypothesis of MIS-C was made and serology (COVID-19 IgG/IgM immunochromatographic rapid test) and RT-PCR nasopharynx/oropharynx swab for COVID-19 were requested. The patient progressed with persistent abdominal pain, several diarrhea episodes and persistent tachycardia. An abdominal CT was requested, disclosing a perforated appendix and a pelvic abscess. The patient underwent appendectomy and exploratory laparotomy, with abscess formation in the pelvis and a drain had been placed in the cavity. The anatomopathological examination of the appendix revealed a vermiform appendix 9.5 × 1.0 cm with a brown serous surface with congested vessels and fibrinous coating. There was luminal obstruction by a fecalith and loss of parietal stratification. Microscopically, the appendix presented ulceration with inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophils and mononuclear cells associated with hemorrhage (Fig. 1A) and extensive areas of wall necrosis with loss of mucosa (advanced phlegmonous/gangrenous phase), (Fig. 1B).

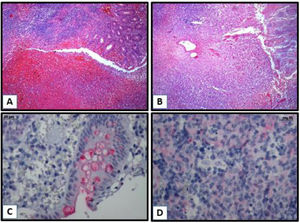

Inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophils and mononuclear cells and hemorrhage (1A); extensive areas of wall necrosis with loss of mucosa - HE (10 X/20 × 4 X/0.10) (1B); positive detection of SARS-CoV-2 N antigen (in red) in the cytoplasm of appendix glands (1C) and cytoplasm of mononuclear cells in the lymphoid nodules (1D), by immunohistochemistry reaction.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed for detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (mouse monoclonal antibody [6H3] -GeneTex Inc., Irvine, CA, USA, 1:500 dilution). Antigen retrieval was performed with 10 mM citrate buffer at pH 6.0. Amplification was achieved by alkaline phosphatase conjugated polymer (Polink-2 AP, GBI Labs cat.D24–110, Bothell, Washington, EUA), revealed by permanent fast red chromogen (GBI-Permanent Red Substrate, GBI Labs cat. C13–120, Bothell, Washington, EUA). The IHC staining was positive in the appendix glands (Fig. 1C) and in mononuclear cells in the lymphoid nodules (Fig. 1D).

The paraffin-embedded appendix tissue was processed for SARS-CoV-2 molecular detection by real-time RT-PCR (rRTPCR) using the SuperScriptTM III PlatinumTM One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and primers and probes that amplify the region of the nucleocapsid N (CDC protocol) and E genes. The human RNAse P gene (RP) was also amplified as a nucleic acid extraction control. The reactions were carried out in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems,Waltham, MA, USA) using the following thermal conditions: incubation at 50 °C for 15 min for the reverse transcription, followed by incubation at 95 °C for 2 min, and 45 cycles of temperature varying from 95 °C for 15 s to 55 °C for 30 s. The RT-PCR was also positive in this case. The reactions (both IHC and RT-PCR) followed standard protocols validated in our laboratories, using positive and negative controls. The detailed protocol is described in a published article from our group.3

Admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for postoperative management, the patient required fluid resuscitation and oxygen support through nasal cannula. Laboratory tests are shown in Table 1. An echocardiogram was performed, and the results were within normal limits. He evolved hemodynamically stable, with an overall clinical improvement and was discharged home after nine days.

Overview of laboratory values.

AST (aspartate aminotransferase); ALT (alanine aminotransferase); INR (International Normal Ratio); CK (creatine kinase); *KOVID Ab (COVID-19 IgG/IgM; Kovalent do Brasil ltda); ** Panbio™ COVID-19 IgG/IgM rapid test device (Alere S/A).

The diagnosis of COVID-19 infection was confirmed by serology and RT-PCR nasopharynx/oropharynx swab that turned out both positive (positive IgG/inconclusive IgM and reagent RT-PCR).

DiscussionIn this case, a preadolescent presented with acute inflammatory abdomen, with gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, which in the context of the current pandemic, led the health care professionals to suspect MIS-C/COVID-19 infection, requesting tests for prompt diagnosis and clinical management. Although rare, there are already some reports in the literature of children and adolescents infected with the novel coronavirus, initially manifesting with acute abdomen and appendicitis. The detection of the virus with the IHC and RT-PCR analysis of the appendix in this case corroborates a possible relationship between appendicitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Individual case reports of pseudoappendicitis and acute surgical abdomen have been reported in the literature in pediatric and adult SARS-CoV-2-positive patients.3,5

Regarding laboratorial findings, the patient had elevated C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, d-dimer (peak at day 4) and ferritin as inflammatory markers, leukocytosis with lymphopenia (lowest value on day 2), besides elevated INR, troponin and creatine kinase in the upper normal limit. No bacterial or other viral agents were detected. According to literature data white blood cell count is usually normal in MIS-C, but leucopenia may be seen, with decreased lymphocyte count. C-reactive protein (CRP) may be normal or increased. Elevation of liver enzymes, muscle enzymes, and myoglobin, and increased level of d-dimer might be seen in severe cases.6

Considering the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, USA) criteria,8 the patient had a history of fever; involvement of two systems, requiring hospitalization (gastrointestinal tract and coagulopathy, presenting elevated d-dimer and INR), in addition to persistent tachycardia, as an early sign of shock in children; laboratory evidence, including an elevated inflammatory marker (CRP) and lymphopenia; and finally, positive RT-PCR and serology for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Regarding the item “no alternative plausible diagnoses”, the fulfillment of the criteria for MIS-C was only retrospectively possible, after the result of anatomopathological analysis, considering that it could only have been an appendicitis case; however, after virus identification in the appendix tissue, the case was attributed as caused by the virus, thus excluding other diagnoses.

Coronavirus disease 2019, first reported in Wuhan, China, in early December 2019, has now become an international pandemic. The causative agent, SARS-CoV-2, binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptors and enters human cells resulting in a wide spectrum of disease, ranging from flu-like illnesses to fatal pneumonia. Besides, SARS-CoV-2 may cause unpredictable complications in various organ systems.1 The possible relationship of viral entry through ACE 2, abundantly present in the terminal ileum, and its relationship with terminal ileitis has been well documented. What is not clear, is whether appendicitis may occur as a complication of SARS-CoV-2 through similar proposed mechanisms related to the inflammation associated with viral entry or reactive lymphoid hyperplasia causing luminal obstruction.4

A recent meta-analysis, which contained 17 studies and 2477 patients, found that 13% of COVID-19 patients had gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms; anorexia was the most prevalent followed by diarrhea and nausea/vomiting. Nonetheless, acute abdomen as a presentation of COVID-19 is rare, and its correlation to COVID-19 features and prognosis remains undetermined.1 The patient presented with features of systemic inflammation and acute abdomen mainly abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea and peritoneal irritation.

In May 2020, the CDC, USA issued a national health advisory to report on cases meeting the criteria for MIS-C. This subset of children develops a dysregulated immune response with host tissue damage and hyperinflammation, resembling Kawasaki disease, toxic shock syndrome, or macrophage activating syndrome, with the median age of onset being 8.3 years. In cases with MIS-C, the majority of children were hospitalized (80%–88%) with most requiring intensive care management (80%) for multiorgan dysfunction. Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular organ systems were the two most commonly affected (92% and 80%, respectively).5 Diagnostic suspicion should be raised in the presence of unexplained persistent fever with unexplained symptomatology following exposure to COVID-19. Limited information currently exists on the clinical course of this life-threatening entity.2 Acute appendicitis is known to be associated with Kawasaki disease, of which MIS-C shares many common clinical and pathologic features, possibly related to appendicular artery vasculitis. In Kawasaki disease, abdominal features may represent more severe disease.4

Considering the gastrointestinal symptoms, the inflammatory profile, and the coagulation dysfunction, associated with a confirmed infection by SARS-CoV-2, the patient was considered suspect for MIS-C. Nevertheless, there was doubt as to whether appendicitis was unrelated event in a patient with asymptomatic COVID-19 infection, or was actually caused by the viral infection itself, with clinical overlap of acute inflammatory abdomen/SIRS/sepsis. The patient was managed with clinical support, due to his good evolution, fitting into a picture of mild MIS-C, which would be confirmed posteriorly by the histological analysis of the appendix.

MIS-C has been considered as a post-infectious hyper inflammatory complication of SARS-CoV-2 since it presents later in the timeline of the epidemic, and MIS-C patients are often PCR negative, and antibody-positive, suggesting a late manifestation.5 However, recent autopsy evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 has a great invasive potential in patients with severe MIS-C, indicating that a direct viral effect on tissues is involved in the pathogenesis of the multisystem inflammation.3 This patient had both RT-PCR nasopharynx/oropharynx swab and IgG positive on admission, suggesting an asymptomatic previous infection, as RT-PCR may persist positive for a long period of time in respiratory samples, even after the rise of IgG titer.9

In a South African study, the authors reported four cases of appendicitis in children with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed infection. Three children were initially diagnosed with acute appendicitis and treated surgically and MIS-C was diagnosed in all three after appendectomies. The fourth child was admitted with clinical appendicitis and tested for SARS-CoV-2, but was managed non-surgically and did not have MIS-C. The study highlights that children with COVID-19 may present with clinical features suggestive of appendicitis or atypical appendicitis as part of MIS-C.4 No fecaliths were found in any of the children requiring appendectomy, possibly supporting inflammation or vasculitis as the pathologic mechanism.4

The cause of appendicitis in MIS-C is unknown, although obstruction of the lumen of the appendix secondary to an initiating factor such as appendicolith formation or mesenteric adenopathy is suspected. Malhotra et al. described 10 patients with confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection that had appendicitis as admission diagnosis, and some were screened positive for appendicoliths. The authors discuss whether acute appendicitis could represent another post-infectious, hyper inflammatory complication of SARS-CoV-2, or rather acute GI infection and inflammation trigger the development of appendicitis. The exact cause of appendicitis remains poorly understood. Although family clusters and a seasonal pattern have been observed, consistent evidence of a viral trigger is lacking.5

Acute abdominal pain in COVID-19 patients poses a diagnostic dilemma to clinicians. Delaying management of the surgical abdomen can result in serious complications and worsen mortality. In contrast, performing unnecessary surgery in COVID-19 patients causes iatrogenic morbidity and mortality, more strain on healthcare resources, and high-risk exposure for healthcare workers involved in operative fields.1 It is essential for optimum clinical and surgical management that pediatric surgeons and clinicians be aware of the GI manifestation of MIS-C and be able to differentiate this novel syndrome from other surgical pathologies that it often mimics.3,7

ConclusionMore studies are needed to clarify the broad clinical spectrum that COVID-19 can present in the pediatric population, with different phenotypes. However, in view of the latest reports in the literature and our finding of viral infection in the IHC and RT-PCR analysis of the appendix, it is necessary for health professionals to consider MIS-C and SARS-CoV-2 infection within their diagnostic hypotheses, when dealing with children with acute abdomen.

FundingThis work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors wish to thank Marisa Dolhnikoff and Cristina T. Kanamura for contribution to the process of pathological analysis of the appendix and for reviewing this text.