Emerging human coronaviruses, including the recently identified SARS-CoV-2, are relevant respiratory pathogens due to their potential to cause epidemics with high case fatality rates, although endemic coronaviruses are also important for immunocompromised patients. Long-term coronavirus infections had been described mainly in experimental models, but it is currently evident that SARS-CoV-2 genomic-RNA can persist for many weeks in the respiratory tract of some individuals clinically recovered from coronavirus infectious disease-19 (COVID-19), despite a lack of isolation of infectious virus. It is still not clear whether persistence of such viral RNA may be pathogenic for the host and related to long-term sequelae.

In this review, we summarize evidence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA persistence in respiratory samples besides results obtained from cell culture and histopathology describing long-term coronavirus infection. We also comment on potential mechanisms of coronavirus persistence and relevance for pathogenesis.

Human coronaviruses (hCoV) were first identified in the 1960s (e.g. strains 229E and OC43) as pathogens associated with upper respiratory tract infections and occasionally with cases of pneumonia in infants and adults.1,2 After 2002, it has been identified five new hCoV including two related to common cold, bronquiolitis and pneumonia (HKU1 and NL63), as well as three etiological agents of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2).3–5

SARS-CoV emerged at the beginning of November 2002 in Guangdong Province, China, and disseminated to 32 countries and regions producing 8437 cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), besides 813 deaths by July 2003; no SARS-CoV related disease has been reported since January 2004.6,7 The Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) was described in 2012 in Saudi Arabia, in a man with acute pneumonia and renal failure; the MERS-CoV was isolated as the etiological agent. From June 2012 to May 2019, there have been a total of 2442 confirmed cases of MERS and 843 related deaths in 27 countries.6,8 Surveillance about suspected MERS-CoV infection is currently recommended by WHO to detect early cases and prevent clusters.9

In late December 2019, cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology were reported in Wuhan, China, and in subsequent weeks, it was identified a novel coronavirus currently named SARS-CoV-2, as the causal agent. Since then, SARS-CoV-2 spread globally causing a pandemic with 147,539,302 cases of coronavirus infectious disease-19 (COVID-19) and 3116,444 deaths (up to April 27, 2021).10 Besides asymptomatic, COVID-19 includes clinical presentations that can be categorized as mild, moderate (no-severe pneumonia), severe (pneumonia), and critical illness.11,12 Chronic conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease and diabetes influence the severity of COVID-19 and time to recovery. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 is usually performed by quantitative RT-PCR and higher viral loads are often associated with severe symptoms13,14; although it has also been reported cases of subjects developing mild COVID-19 with high viral loads, achieving clearance of infectious virus and viral RNA within one and three weeks after symptoms onset, respectively.15

Long-term viral RNA detection has also been described in patients recovered from COVID-19, despite no identification of infectious viral particles.16,17 Such observations have supported the criteria for releasing COVID-19 patients from isolation even before obtaining a negative RT-PCR test.18 However, it is still not clear whether SARS-CoV-2 RNA persistence might be pathogenic for the host, despite a lack of assembled infectious virus.

Here, we summarize evidence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA persistence in respiratory samples besides results from cell culture and histopathology describing long-term productive and non-productive coronavirus infection in epithelial, myeloid and neural cells. We also comment on possible mechanisms of coronavirus persistence and relevance for pathogenesis.

Long-term detection of SARS-CoV-2-RNA in clinical samplesLong-term SARS-CoV-2-RNA detection is frequent19–21 in 13–45% of patients with COVID-19.22–25 In the third week after symptom onset, RT-PCR positive tests can be detected in 43–66% of patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 or in those hospitalized,25,26 and then occurs a progressive reduction to 32% in the fourth week, whereas most of cases display negative tests in the sixth-to-seventh weeks. As negative results are prevalent since the fourth week, virus RNA persistence could be considered after 28 days of symptom onset.23,25,27,28

In a retrospective study (n = 2142), patients with critical COVID-19 were longer positive for viral RNA than non-critically ill patients (median time, 24 days vs. 18 days, respectively), according to analysis of nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS); similarly, serum biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-8, aspartate aminotransferase, IL-2 receptor, D-dimer and C-reactive protein remained higher in the former group, all along virus nucleic acid persistence.29 Inside the non-critical group, 20% of subjects with low IgM levels also remained positive for viral RNA up to 73 days after symptom onset, with respect to non-critical COVID-19 patients with higher IgM levels that cleared earlier the viral infection. Convalescent plasma was administered to persistently RNA positive patients resulting in test negativization within two weeks after this passive immunization, supporting that anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are important for viral clearance.29 Another study that included 43 patients with mild COVID-19 and six with severe disease reported median time for negative RT-PCR tests of 22.7 days and 33.5 days, respectively.16 Additional reports have shown that viral load is significantly higher in patients with severe disease than in those with mild COVID-19 and that viral RNA clearance is delayed in subjects with severe symptoms or in patients under corticosteroid treatment.30,31

By contrast, another study that analyzed upper respiratory samples from patients categorized in groups of moderate-to-severe (hospitalized) and mild disease, reported that the hospitalized group displayed viral RNA for 28.0 ± 10.1 days, whereas patients with mild COVID-19 were positive for 35.3 ± 8.0 days, suggesting this last group was slower to eliminate viral infection. Interestingly, in this same study IgG titers were lower in mild than in hospitalized patients, thus, higher antibody titers are associated with enhanced viral elimination but also could be related to severe forms of COVID-19.23 In this regard, it has been observed significantly increased serum titers of IgM, IgA and IgG3 antibodies against the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike envelope protein in severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients, compared to patients with mild disease. Similar results have been observed during titration of neutralizing antibodies, which are always higher in hospitalized individuals.32,33In vitro assays with sera from severe patients revealed high levels of a low-fucosylated IgG1 which, similarly to IgG3, forms immune complexes with SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped VSV viruses, that bind and activate FCγRIIIα signaling to produce high levels of IL-6, TNF and IL-1β in monocytes and natural killer cells, suggesting that the antibody effector function contribute to the “storm of cytokines” observed in severe COVID-19.34 Thus, quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the antibody response might be determinant in kinetics of viral clearance and the outcome of the disease.

Additionally to clinical status, age is another factor associated to SARS-CoV-2 RNA persistence.22 In this respect, analysis by age and disease severity have shown that viral RNA shedding is significantly longer in respiratory samples from subjects older than 60 years that coursed with severe COVID-19 than in younger people under similar clinical conditions.31 A study with 384 patients of a median age of 58 years reported that elderly was a significant factor associated with prolonged viral RNA detection, with median time of 32 days (range 4–111 days); patients older than 70 years showed virus genome persistence over 70 days.35

Despite only some studies have evaluated presence of replication-competent virus, possibly due to infrastructure limitations to handle pathogens at Biosafety Level-3, it is currently clear that RNA detection is of longer duration than isolation-time of infectious virus in cell culture, since samples become negative to viable virus within eight to ten days after symptoms onset.36–38 Nevertheless, studies that included patients with severe COVID-19 reported isolation of infectious viral particles at day 20.19,36 Probability of detection of infectious virus at 15 days post-symptom onset has been estimated lower than 5%,36 suggesting that even though viral RNA is long-term maintained in convalescent patients, they might not be contagious through respiratory secretions. Nevertheless, Li et al. described isolation of viable virus in Vero E6 cells from sputum collected at 73 and 102 days after disease onset from two elderly patients clinically recovered, although they still showed persistent lung abnormalities by chest computed tomography. In this study, reinfection was not considered as responsible for longstanding viral shedding, since sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genome from two consecutive samples (separated by 20 days) collected from two subjects, revealed 100% sequence identity (only one substitution in one paired sample), suggesting no new viral infection had occurred and that few prolonged viral RNA carriers from the aged group might propagate infection longer than expected.17

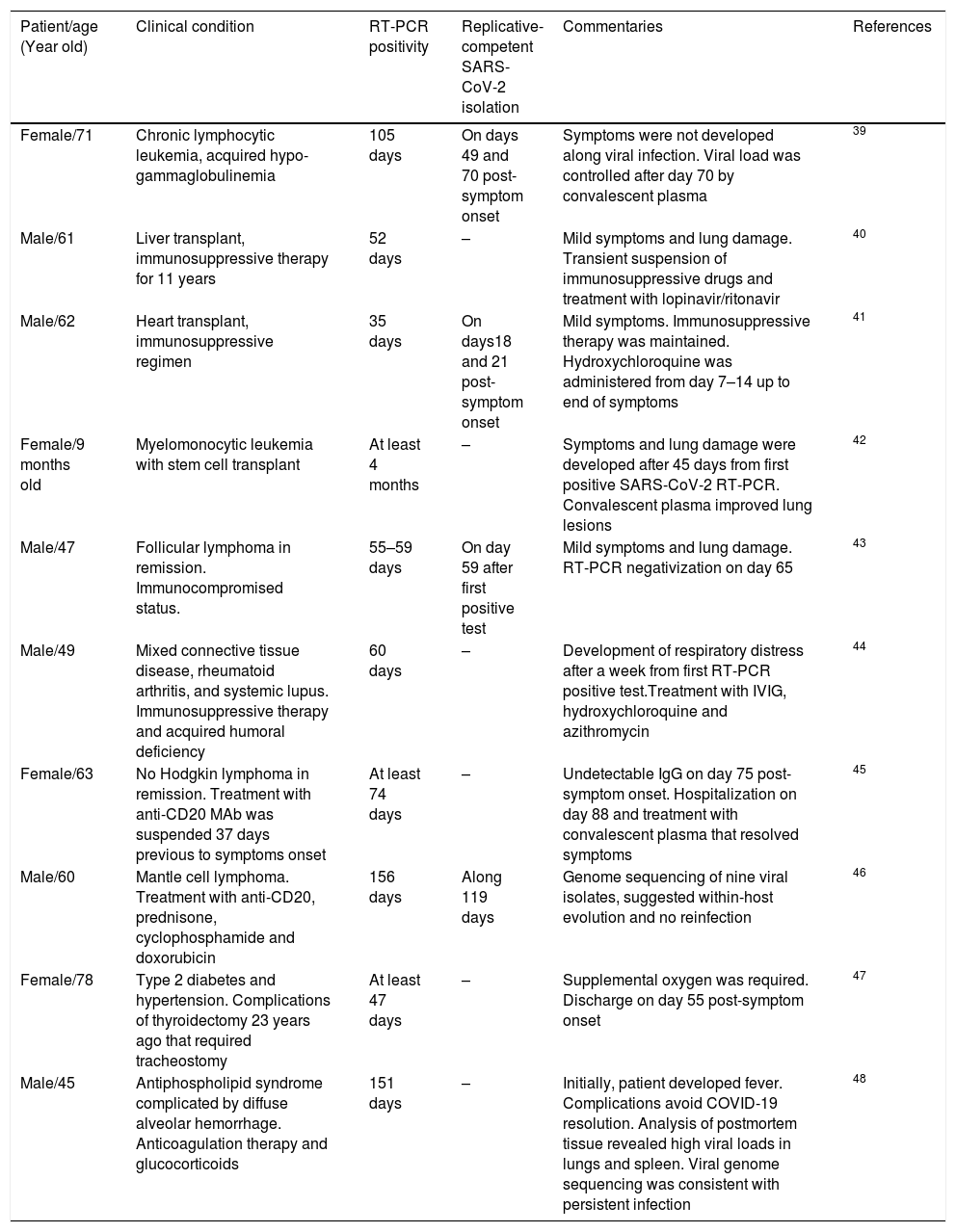

Furthermore, an immunocompromised state is also associated to high frequency of SARS-CoV-2 persistence, as it has been observed in oncologic patients and transplant recipients.39–48 Worth mentioning, viral RNA of NL63-CoV has also been detected up to ∼60 days in cancer patients that develop respiratory symptoms, whereas 229E-CoV was detected over a period of 77 days in a pediatric patient with a brain tumor, indicating coronaviruses are opportunistic pathogens.49,50Table 1 displays a summary of case reports for SARS-CoV-2 infected patients that presented immunosuppression.

Case reports of immunosuppressed patients with long-term SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection.

| Patient/age (Year old) | Clinical condition | RT-PCR positivity | Replicative-competent SARS-CoV-2 isolation | Commentaries | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female/71 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acquired hypo-gammaglobulinemia | 105 days | On days 49 and 70 post-symptom onset | Symptoms were not developed along viral infection. Viral load was controlled after day 70 by convalescent plasma | 39 |

| Male/61 | Liver transplant, immunosuppressive therapy for 11 years | 52 days | – | Mild symptoms and lung damage. Transient suspension of immunosuppressive drugs and treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir | 40 |

| Male/62 | Heart transplant, immunosuppressive regimen | 35 days | On days18 and 21 post-symptom onset | Mild symptoms. Immunosuppressive therapy was maintained. Hydroxychloroquine was administered from day 7–14 up to end of symptoms | 41 |

| Female/9 months old | Myelomonocytic leukemia with stem cell transplant | At least 4 months | – | Symptoms and lung damage were developed after 45 days from first positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR. Convalescent plasma improved lung lesions | 42 |

| Male/47 | Follicular lymphoma in remission. Immunocompromised status. | 55–59 days | On day 59 after first positive test | Mild symptoms and lung damage. RT-PCR negativization on day 65 | 43 |

| Male/49 | Mixed connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus. Immunosuppressive therapy and acquired humoral deficiency | 60 days | – | Development of respiratory distress after a week from first RT-PCR positive test.Treatment with IVIG, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin | 44 |

| Female/63 | No Hodgkin lymphoma in remission. Treatment with anti-CD20 MAb was suspended 37 days previous to symptoms onset | At least 74 days | – | Undetectable IgG on day 75 post-symptom onset. Hospitalization on day 88 and treatment with convalescent plasma that resolved symptoms | 45 |

| Male/60 | Mantle cell lymphoma. Treatment with anti-CD20, prednisone, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin | 156 days | Along 119 days | Genome sequencing of nine viral isolates, suggested within-host evolution and no reinfection | 46 |

| Female/78 | Type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Complications of thyroidectomy 23 years ago that required tracheostomy | At least 47 days | – | Supplemental oxygen was required. Discharge on day 55 post-symptom onset | 47 |

| Male/45 | Antiphospholipid syndrome complicated by diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Anticoagulation therapy and glucocorticoids | 151 days | – | Initially, patient developed fever. Complications avoid COVID-19 resolution. Analysis of postmortem tissue revealed high viral loads in lungs and spleen. Viral genome sequencing was consistent with persistent infection | 48 |

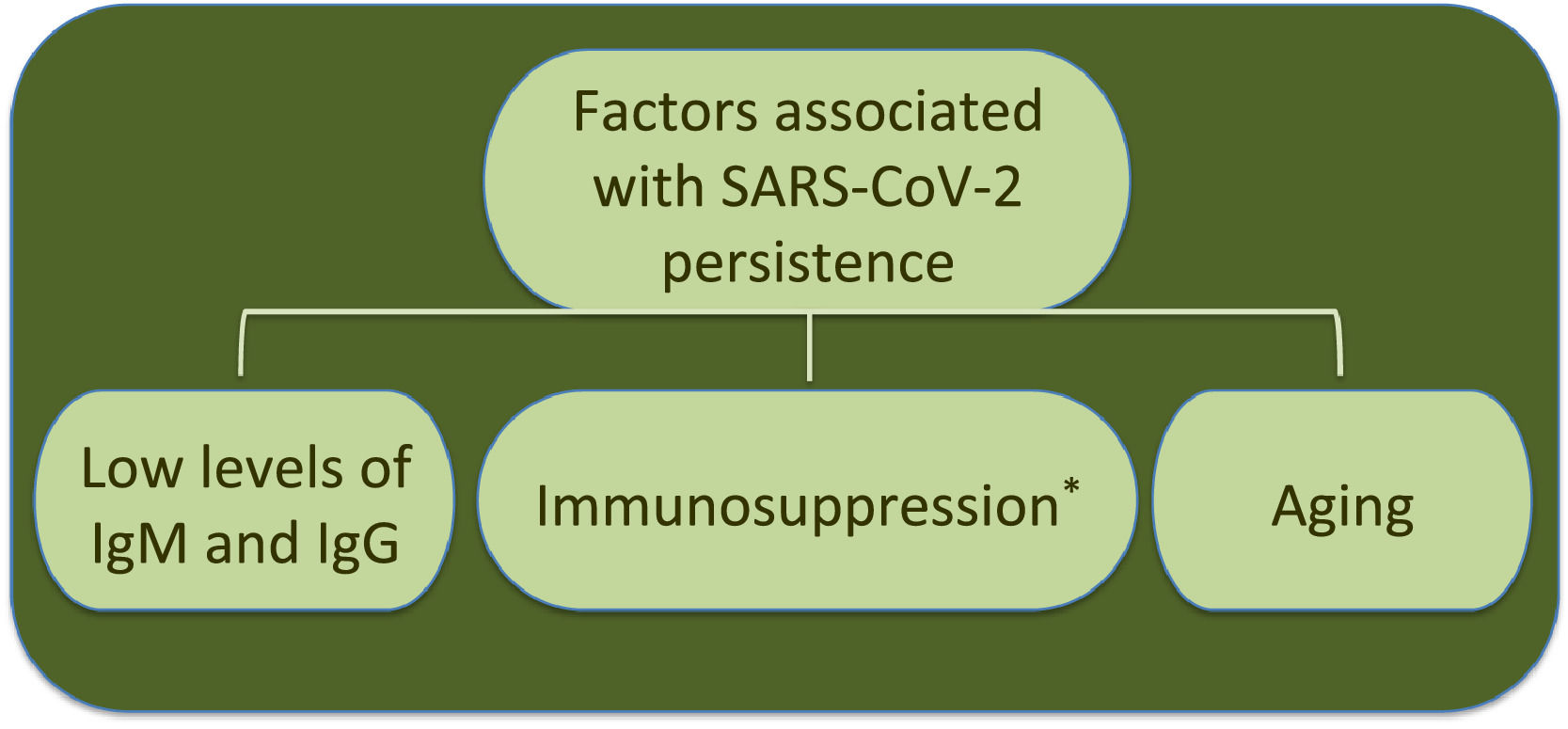

Interestingly, the longest time for RNA detection was 151 days, in a man with anti-phospholipid syndrome and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage that developed complications and coinfection with Aspergillus fumigatus, leading to fatal outcome.48 Another case of prolonged SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and isolation of replication-competent virus showed positivity for 105 and 70 days, respectively, in a woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia that developed a secondary hypogammaglobulinemia.39 Viral infection coursed asymptomatic, similarly to many SARS-CoV-2 infections in immunocompromised patients. Therefore, immunosuppression entails viral RNA persistence, as also occurs in some elderly people (Fig. 1). However, it is still uncertain the biological relevance and mechanisms associated with long-term coronavirus persistence. Therefore, in the following section we comment some findings in cell culture and histopathology that propose coronavirus persistence might contribute to pathogenesis in infected individuals.

Coronavirus persistence in experimental modelsViral persistencePersistent viral infections are established by concurrence of molecular and immunological events that allow the virus to evade the immune response and acquire a gene expression program to regulate both its own replication (to avoid killing the host cell) and host gene expression, enabling a long-lasting virus–host interaction.51,52 Persistence can occur as productive or non-productive infection. In the former type of persistence, virions are detected constantly or intermittently, whereas in the latter type, infectious viruses are not produced, regardless of viral genome remaining intracellular and expression of some viral proteins may take place.53 Under such condition, kinetics of detection of the persistent virus genome might be determined by rates of residual RNA replication and its catabolic degradation, as well as by lysis of viral RNA positive cells through cell-mediated cytotoxicity.53

Thus, SARS-CoV-2 possibly establishes a non-productive viral persistence in some individuals, since infection progress from a productive state to a persistent condition with measurable viral RNA but undetectable release of infectious virus; although shedding of viable virus is apparently of longer duration in immunocompromised and elderly patients, than in those immunocompetent.

Contribution of SARS-CoV-2 RNA persistence to COVID-19 pathogenesis is not currently understood but it could not be discarded this viral RNA and possibly some viral proteins still expressed, might be continual stimuli that activate at least innate immune receptors, maintaining an inflammatory condition up to complete viral clearance.54

Evidence of persistence in epithelial cellsA non-productive infection by hCoV in respiratory epithelium was described by Loo et al. in an in vitro model of infection of human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) with 229E-CoV and OC43-CoV.55 Kinetics of replication of 229E-CoV was faster than that of OC43-CoV, with viral RNA copies and infectious virus titers peaking at 24 and 96 h post-infection (hpi), respectively. At seven days post-infection, both types of coronavirus-infected HBECs showed similar number of viral RNA copies (∼105/ml), despite infectious virus was only isolated from OC43-CoV infected cells (∼104 TCID50/ml), suggesting that genomic RNA from 229E-CoV persisted intracellular without virions assembly. Such observation correlates with detection of genomic and subgenomic viral RNA from SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples from COVID-19 patients, even in absence of virus isolation.56 Of relevance, 229E-CoV induced synthesis of high levels of type-I and type-III interferon in HBECs, contrasting with results by OC43-CoV infection. Also, a productive persistent infection was described at 28 days post-infection in OC43-CoV-infected airway epithelial cells, with viral loads of ∼107 virus genome copies/sample and undetectable synthesis of IFN-λ.57 Possibly both, low and slow kinetics of replication of the OC43-CoV contributed to evade its early detection by intracellular innate immune recognition receptors, allowing a prolonged productive persistence.55

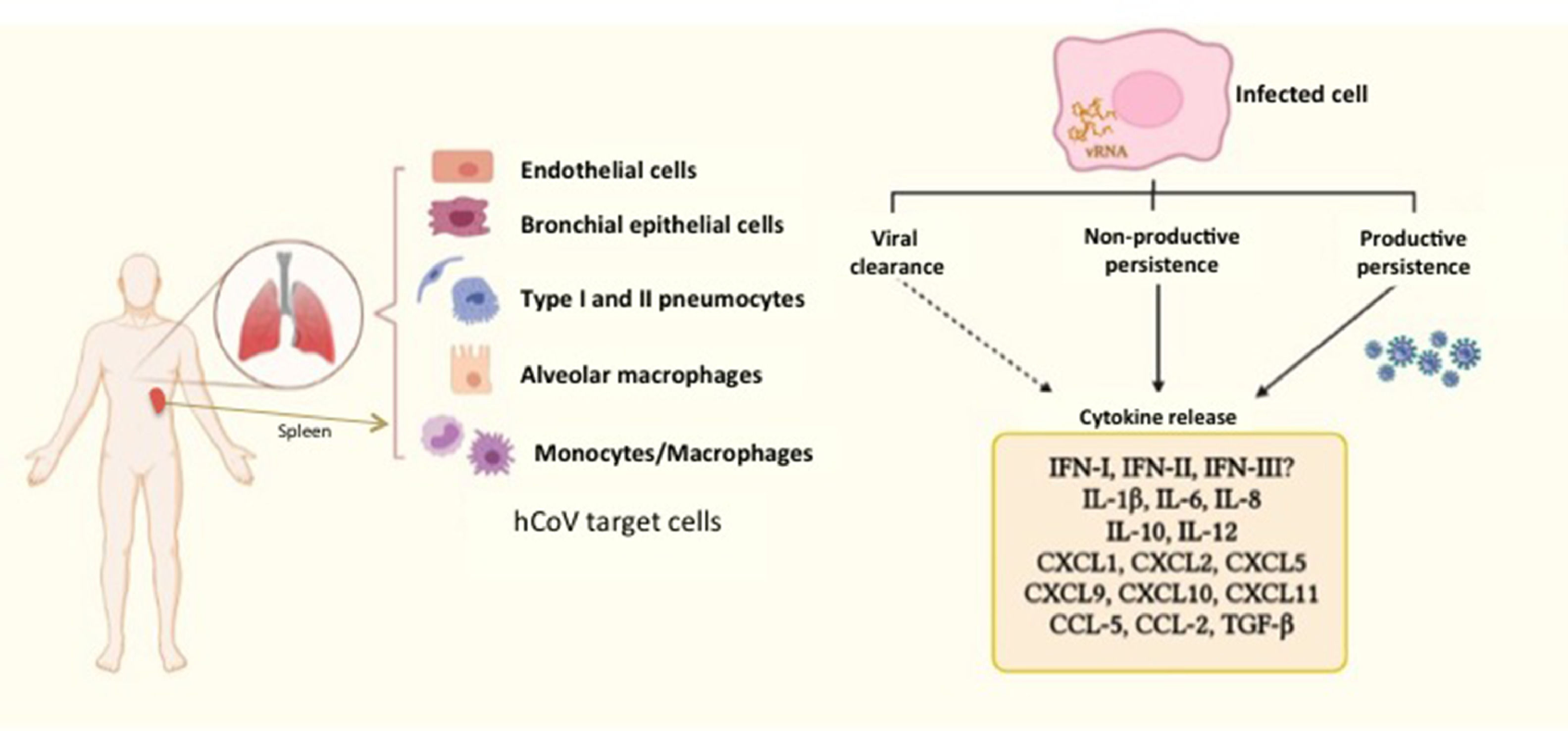

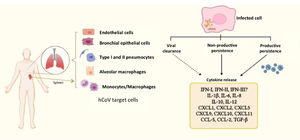

A comparative study of infection of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in lung tissue explants along 48 h showed that both viruses have tropism by type I and type II pneumocytes as well as by alveolar macrophages. However, SARS-CoV-2 generated higher titers of infectious virus than SARS-CoV (3.2-fold increase), associated with a lack of induction of IFN-I, IFN-II and IFN-III, but augmented transcription of IL-6, MCP-1, CXCL1, CXCL5 and CXCL10. In this case, SARS-CoV induced mRNA expression of six additional proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that were not stimulated by SARS-CoV-258; authors suggested that such exacerbated proinflammatory state could be related to the higher fatality rate of SARS-CoV with respect to SARS-CoV-2. This study did not evaluated virus persistence but considered a particular capability of evasion of the innate immune response is characteristic of SARS-CoV-2, allowing early high viral loads and efficient dissemination to new hosts. In this regard, Xia et al. described mechanisms of inhibition of IFN-I synthesis and response exerted by some structural, non-structural and accessory proteins of SARS coronaviruses. Particularly, non-structural proteins 1 and 6 from SARS-CoV-2 were more potent to inhibit IFN-α signaling than the equivalent proteins from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV leading to higher viral replication.59 Thus, it could be proposed that such poor IFN mediated response might at least partially promote SARS-CoV-2 persistence, (besides a modest antibody response, as considered above), whereas it is stimulated a continuing synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which contribute to COVID-19 pathogenesis (Fig. 2).

Human coronaviruses (hCoV) infect different types of cells from respiratory and non-respiratory tissues. hCoV can be cleared by the antiviral immune response, although they are also able to persist either in productive or non-productive manner. Persistently infected cells and some cells that cleared the virus (e.g. myeloid cells) show an activation state characterized by a chronic production of cytokines and chemokines, contributing to inflammation. The dashed arrow represents particularly those cells producing cytokines, notwithstanding virus had been eliminated. The different types of hCoV can differentially inhibit type-I, II and III interferon through activity of non-structural proteins, which are key players in evasion of the innate immunity. vRNA, viral RNA.

Analysis of postmortem lung tissue from individuals who died of COVID-19 has shown wide presence of pneumocytes and endothelial cells positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by in situ hybridization, even though diagnosis in some patients had occurred 30–40 days earlier, supporting a long-lasting viral infection.60

Persistence in myeloid cellsEpithelial cells might not be the unique reservoir of hCoV since monocytes and macrophages have also been described as permissive cells. Particularly, 229E-CoV infects human peripheral blood monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM), although infectious virus are below limit of detection at 72 hpi, even though spike protein remains detectable by immunofluorescence during at least five days,61 suggesting myeloid cells enable a non-productive infection. Furthermore, infection of the human monocytic THP-1 cell line with 229E-CoV allows carrier persistence for at least two months, characterized by 1–2% of infected cells and low viral titers (101–102 TCID50/ml). Interestingly, both primary monocytes and THP-1 cells infected by 229E-CoV secreted CCL5, CXCL10, CXCL11 and TNF-α in supernatants61; thus, 229E-CoV persists in monocytes with low to undetectable release of infectious virus and might contribute to inflammation. Notwithstanding, it is still controversial whether myeloid cells are permissive to SARS-CoV-2. Boumaza et al. showed that primary human monocytes and MDM were infected in vitro by SARS-CoV-2, but genome replication was active only during the first 48 hpi in monocytes. Interestingly, viral contact induced expression of IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, TNF-α and TGF-β1 in both monocytes and macrophages, suggesting an M1/M2 mixed phenotype.62,63 Additionally, peripheral blood monocytes from COVID-19 patients expressed higher levels of CD163 than healthy controls, whereas this M2 macrophage marker has also been observed in histopathology from lung tissue.62,64 On the other hand, a population of large non-classical monocytes CD14+/CD16+ has been identified in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of COVID-19 patients.65 This cell population is characterized by altered morphology (e.g. vacuolated) and expression of significantly higher levels of CD80 and CD206 with respect to the peripheral blood monocytes of normal size; IL-6 and TNF-α are also expressed at higher levels in monocytes from COVID-19 patients than that from healthy donors. Even though viral infection was not evaluated in such large monocytes, an in vitro assay of pseudovirus entry, coupled to green florescence signal, showed up to 25% of primary monocytes were infected, suggesting that myeloid cells are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection.65

Histopathology of postmortem hilar lymph nodes and spleens from COVID-19 subjects, showed peripheral macrophages (CD68+) and tissue-resident macrophages (CD169+) expressing viral nucleocapsid protein, whereas T and B lymphocytes were negative for such viral antigen. Additionally, only macrophages infected by SARS-CoV-2 expressed IL-6.66 Another study in pulmonary tissue showed through electron microscopy SARS-CoV-2 particles localized in cytoplasm of pneumocytes and alveolar macrophages.67

Such experimental evidence supports the hypothesis that monocytes/macrophages allow at least a transitory productive infection by SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2); afterwards, a non-productive infection is set up, whereas myeloid cells sustain synthesis of proinflammatory and immunomodulatory cytokines. Possibly immunomodulatory cytokines reflect an overproduction of proinflammatory factors that contribute to disease severity and possibly to long-term sequelae observed in convalescent COVID-19 patients.68,69 Further studies are necessary to determine whether myeloid cells may be, not only targets, but also vehicles for viral dissemination to extra pulmonary tissues and long-term viral reservoirs.

Persistence in neural cellsNeurological manifestations have been described in some hCoV individuals infected, including SARS-CoV-2. Central nervous system (CNS) damage may be consequence of neuroinvasion either by hematogenous or transneural routes, although indirect damage such as that produced by immunopathogenesis is also considered (reviewed by Abdelaziz and Waffa,70 and by Kumar et al.71).

Early studies focused on coronavirus neurotropism described susceptibility of human primary astrocytes and microglia to 229E-CoV and OC43-CoV, even though infection with 229E-CoV occurred in absence or at a low-to-undetectable production of viral particles.72 Both 229E-CoV and OC43-CoV have displayed capability to persist in astrocytoma, neuroblastoma and oligodendrocytic human cell lines for 25–40 passages, with constant levels of viral RNA, whereas viral titers may oscillate between undetectable to 107 TCID50/ml.73,74 A mouse model to study neuropathology associated with OC43-CoV infection showed in 30% of surviving mice, after one year of their recovery from acute encephalitis, smaller hippocampi, clusters of activated microglia and persistent viral RNA; all these findings associated with altered limb clasping reflex. Remarkably, viral protein synthesis was undetectable. In the same study, infection of primary neural cell cultures with OC43-CoV induced overproduction of TNF-α and increased death of infected cells. Therefore, long-term neuropathology in mice correlated with persistence of viral RNA and activated microglia, which might be associated with increased cytotoxicity.75

The characteristic coronavirus persistence in CNS associated with a lack of detection of infectious virus has been partially explained by Liu et al. in an in vitro model of murine oligodendrocytes persistently infected by mouse hepatitis coronavirus. In such oligodendrocytic cell line, subgenomic viral RNAs and viral proteins were produced constantly, although infectious viruses were not detected by titration assays. However, electron microscopy and biochemical techniques revealed assembly of defective viruses with scarce spike protein in the envelope, and consequently, impaired infectivity.76 Other persistent viral infections are characterized by long-term detection of viral genomic RNA, possibly also mRNA, but in absence of infectious virus, such as respiratory syncytial virus,77 Zika virus78 and measles virus.79 In regard to measles, immunocompetent mice surviving acute infection show persistent viral RNA and mRNA up to two years post-infection, despite viral antigens are not detected. However, depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes reactivates viral protein expression, which is associated with development of neuropathology, indicating adaptive immune response controls measles virus replication although without clearance, leading to a long-term “dormancy”, unless a transient immunosuppression occurs, allowing reactivation of viral replication.79 Interestingly, it has been observed that anti-SARS-CoV-2 specific CD8+T cells are increased in the respiratory tract of subjects with persistent viral RNA80; possibly this immune cells prevent virus transmission or avoid completion of the virus replication cycle, since contact tracing studies have not identified cases of transmission from long-term viral RNA carriers.20,80

Concluding remarksHere we exposed that SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses potentially establish a long-term, non-productive persistent infection in epithelial, myeloid and neural cells, which might be associated with prolonged synthesis of inflammatory mediators and cytotoxicity, contributing to airway chronic inflammation and/or neurological sequelae, until viral clearance is achieved.

Altered synthesis of IFN-I, IFN-II and IFN-III, besides a deficient production of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG may be determinant events that contribute to long-term infection in some individuals.

Further research is necessary to understand whether coronavirus RNA persistence has impact not only on viral transmission but also in pathogenesis.

Funding informationThis work was supported by the grant PAPIIT-UNAM number IA205521.