Hookworm infection in humans is usually caused by the helminth nematodes Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale.1–3 It is found in approximately 25% of the world population, especially in poor tropical and subtropical areas.1–3 In Peru, a prevalence of 14% is reported, the majority of cases are in Madre de Dios, Amazonas, Loreto, and Cusco.1 Similar figures have been reported in Colombia and Bolivia.1–3 The infection is acquired by direct contact of the skin with contaminated soil and fecal-oral route.3

The majority of infected patients remain asymptomatic and iron deficiency anemia due to chronic losses through the digestive tract is the main complication.4 Both species adhere to the mucosa of the small intestine, absorb blood, cause erosions, ulcers, and favor blood loss by secretion of anticoagulant substances and enzymes. The amount of blood loss caused by hookworms in an adult is about 0.05 to 0.3 ml for Ancylostoma duodenale and 0.01 to 0.04 ml for Necator americanus.4–6 The resulting anemia can be mild, moderate or severe, depending on the parasitic load (number of eggs eliminated per gram of feces).3 However, manifest gastrointestinal bleeding is rare.4

Herein, we present the case of a 91-year-old male farmer, from Amazonas, with no relevant medical or family history. He reports two weeks of asthenia and shortness of breath at moderate efforts. One day before his admission he presented hematemesis, dizziness and syncope. On physical examination the patient’s vital signs were unstable with tachycardia and hypotension, he was pale, with no adenopathies, had rhythmic heart sounds with a multifocal systolic murmur, soft abdomen, depressible without visceromegaly, with disorientation in time and space.

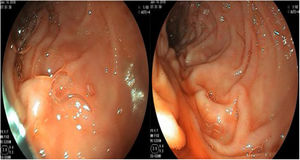

Laboratory tests revealed hemoglobin of 1.9 g/dL, hematocrit 8%, leukocytes 3.5 × 103/uL (eosinophils 10%) and platelets 232 × 103/uL, urea 63 and creatinine 2, complete liver and coagulation profile within normal ranges, rapid test for HIV and ELISA for HTLV-1 negative. The upper endoscopy showed multiple cylindrical worms of approx. 20 mm in bulb and second duodenal portion adhered to the mucosa (Fig. 1).

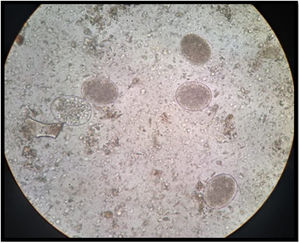

Fecal examination by rapid sedimentation of Lumbreras showed hookworm eggs and few adult parasites (Fig. 2). Colonoscopy was performed where dead parasites were found without neoplastic lesions.

The patient was treated with Albendazole 400 mg q24 h for three days, mebendazole 100 mg q24 h for five days and multiple blood transfusions. The patient evolved favorably and two weeks thereafter the parasitological examination in feces was negative.

These hookworms live in the small intestine, lay eggs that are eliminated in the feces which, under optimal conditions, mature and produce larvae that when in contact with the skin, penetrate it and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed. The larvae reach the small intestine, completing its cycle in the intestine.4–7

The diagnosis is based on the identification of eggs in feces of patients with hypochromic microcytic anemia and eosinophilia.4–6 However, sometimes there is no increased total eosinophil count, as in this case. Although the eggs of the two species can not be differentiated by basic light microscopy, the adult worms do have differences: the ancylostoma is larger and the structure of its mouth opening has two pairs of teeth or hooks of equal size, and the necator a pair of cutting plates.3–6

The clinical presentation varies depending on the phase of the parasite and the intensity of the infection, being found from cutaneous, respiratory, non-specific digestive findings such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea to failure to thrive in the case of children due to malabsorption and malnutrition.2,8

In Peru, only two cases of gastrointestinal bleeding have been reported as a form of presentation of this infection: in a 27-day old patient with severe anemia and melena9 and in a 34-year-old male patient from the jungle with low digestive hemorrhage. Both cases were also diagnosed through endoscopic evaluation.10 This is the first case of uncinariasis reported in the country of an older adult patient with clinical manifestation of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with severe anemia and endoscopic demonstration of the adult worm.

Most reports of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to Ancylostoma duodenale come from endemic areas like China, where Tan et al. reported a case of massive hemorrhage due to duodenal ancylostoma diagnosed by endoscopic capsule.11 In addition, Wei et al. reported on 424 Chinese patients with overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding diagnosed by endoscopy, colonoscopy, capsule endoscopy, or double-balloon enteroscopy, all of them with good response to medical treatment.12

The recommended treatment is single oral dose of albendazole 400 mg. However, failures have been reported, so it is recommended to administer 400 mg of albendazole for three consecutive days or as a single 800 mg dose.3 Our patient persisted with positive stool tests, so he received a longer course with mebendazole for five more days and the expected clinical and laboratory response was achieved.

In conclusion, infection with Ancylostoma duodenale usually manifests clinically as iron deficiency anemia in tropical areas, but presentation as digestive hemorrhage associated with massive infestation and is infrequent.9,10

It is important to consider this pathology within the differential diagnosis in cases of gastrointestinal bleeding of patients from endemic areas. Anti-helminth therapy is very effective with rapid clinical improvement as observed in our patient.9

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.