Streptomyces is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria that grows in various environments, and its shape resembles filamentous fungi. The morphological differentiation of Streptomyces involves the formation of a layer of hyphae that can differentiate into a chain of spores. The most interesting property of Streptomyces is the ability to produce bioactive secondary metabolites, such as antifungals, antivirals, antitumorals, anti-hypertensives, immunosuppressants, and especially antibiotics. The production of most antibiotics is species specific, and these secondary metabolites are important for Streptomyces species in order to compete with other microorganisms that come in contact, even within the same genre. Despite the success of the discovery of antibiotics, and advances in the techniques of their production, infectious diseases still remain the second leading cause of death worldwide, and bacterial infections cause approximately 17 million deaths annually, affecting mainly children and the elderly. Self-medication and overuse of antibiotics is another important factor that contributes to resistance, reducing the lifetime of the antibiotic, thus causing the constant need for research and development of new antibiotics.

Streptomyces is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria that grows in various environments, with a filamentous form similar to fungi. The morphological differentiation of Streptomyces involves the formation of a layer of hyphae that can differentiate into a chain of spores. This process is unique among Gram-positives, requiring a specialized and coordinated metabolism. The most interesting property of Streptomyces is the ability to produce bioactive secondary metabolites such as antifungals, antivirals, antitumoral, anti-hypertensives, and mainly antibiotics and immunosuppressives.1–3 Another characteristic is of the genus is complex multicellular development, in which their germinating spores form hyphae, with multinuclear aerial mycelium, which forms septa at regular intervals, creating a chain of uninucleated spores.4

When a spore finds favorable conditions of temperature, nutrients, and moisture, the germ tube is formed and the hyphae develops. The aerial hyphae follows, and a stage set initiates the organization of various processes such as growth and cell cycle. Esporogenic cell may contain 50 or more copies of the chromosome; the order, position, and segregation of chromosomes during sporulation is linear, which involves at least two systems (ParAB and FtsK), which lead to differentiation and septation of apical cells into chains of spores. Several other genes that are essential for the sporulation of aerial hyphae have been reported in S. coelicolor, for example, the genes whiG, whiH, whiI, whiA, whiB, and whiD. The explanation for the presence of spores in Streptomyces is probably that these fragments appeared mycelial under selective pressure, which might involve the need to survive outside of plants and invertebrates, or in extreme environments.

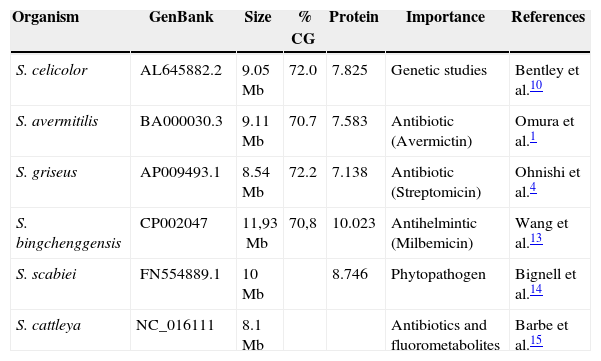

The ability of the spores to survive in these hostile environments must have been increased due to the pigment and aroma present in the spores in some species,5 which stimulates cell development and secondary metabolite production.6 Another important point is the tip of the hypha, which is considered to be the most important region where membrane proteins and lipids may be secreted, especially in the apical area of growth.7 In some Streptomyces, secondary metabolism and differentiation can be related.8,9 Phylogenetically, Streptomyces are a part of Actinobacteria, a group of Gram-positives whose genetic material (DNA) is GC-rich (70%) when compared with other bacteria such as Escherichia coli (50%). The great importance given to Streptomyces is partly because these are among the most numerous and most versatile soil microorganisms, given their large metabolite production rate and their biotransformation processes, their capability of degrading lignocellulose and chitin, and their fundamental role in biological cycles of organic matter.10 Two species of Streptomyces have been particularly well studied: S. griseus, the first Streptomyces to be used for industrial production of an antibiotic - streptomycin, and S. coelicolor, the most widely used in genetic studies. Various strains have been sequenced and their genomes have been mapped (Table 1).

Streptomyces with their available genome sequence.

| Organism | GenBank | Size | % CG | Protein | Importance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. celicolor | AL645882.2 | 9.05Mb | 72.0 | 7.825 | Genetic studies | Bentley et al.10 |

| S. avermitilis | BA000030.3 | 9.11Mb | 70.7 | 7.583 | Antibiotic (Avermictin) | Omura et al.1 |

| S. griseus | AP009493.1 | 8.54Mb | 72.2 | 7.138 | Antibiotic (Streptomicin) | Ohnishi et al.4 |

| S. bingchenggensis | CP002047 | 11,93Mb | 70,8 | 10.023 | Antihelmintic (Milbemicin) | Wang et al.13 |

| S. scabiei | FN554889.1 | 10Mb | 8.746 | Phytopathogen | Bignell et al.14 | |

| S. cattleya | NC_016111 | 8.1Mb | Antibiotics and fluorometabolites | Barbe et al.15 |

The genome of S. coelicolor, for example, encodes a large number of secreted proteins (819), including 60 proteases, 13 chitinases/chitosanases, eight cellulases/endoglucanases, three amylases, and two pactato lyases. Streptomyces are also important in the initial decomposition of organic material, mostly saprophytic species.11

The production of most antibiotics is species specific, and these secondary metabolites are important so the Streptomyces spp. can compete with other microorganisms that may come in contact, or even within the same genus. Another important process involving the production of antibiotics is the symbiosis between Streptomyces and plants, as the antibiotic protects the plant against pathogens, and plant exudates allows the development of Streptomyces.12 Data in the literature suggest that some antibiotics originated as signal molecules, which are able to induce changes in the expression of some genes that are not related to a stress response.11

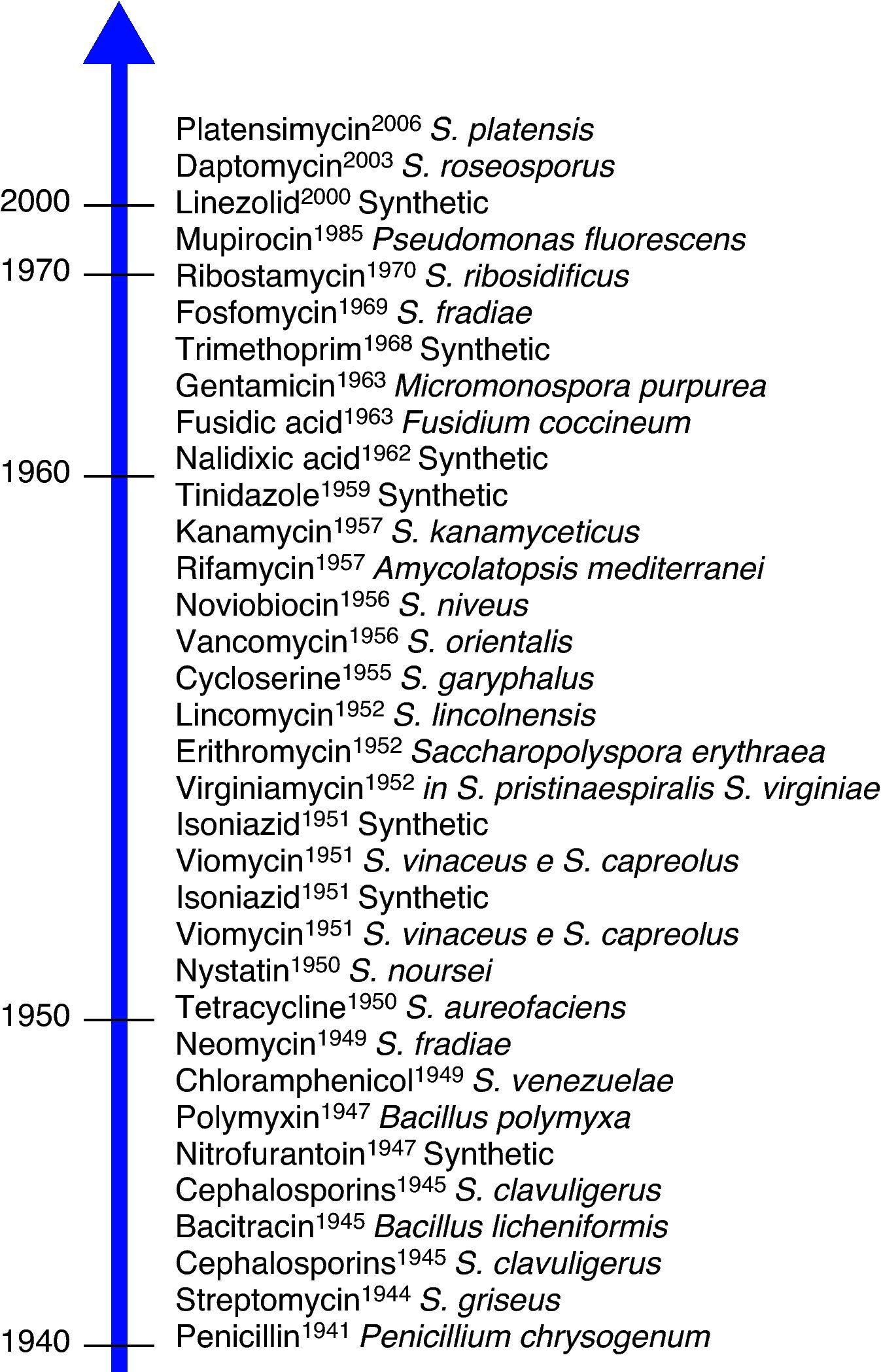

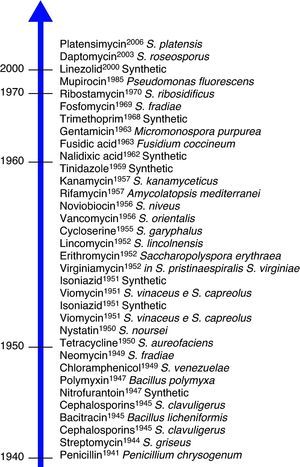

AntibioticsDespite the success of the discovery of antibiotics, and advances in the process of their production, infectious diseases still remain the second leading cause of death worldwide, and bacterial infections cause approximately 17 million deaths annually, affecting mainly children and the elderly. The history of antibiotics derived from Streptomyces began with the discovery of streptothricin in 1942, and with the discovery of streptomycin two years later, scientists intensified the search for antibiotics within the genus. Today, 80% of the antibiotics are sourced from the genus Streptomyces, actinomycetes being the most important.16 This can be seen in Fig. 1.

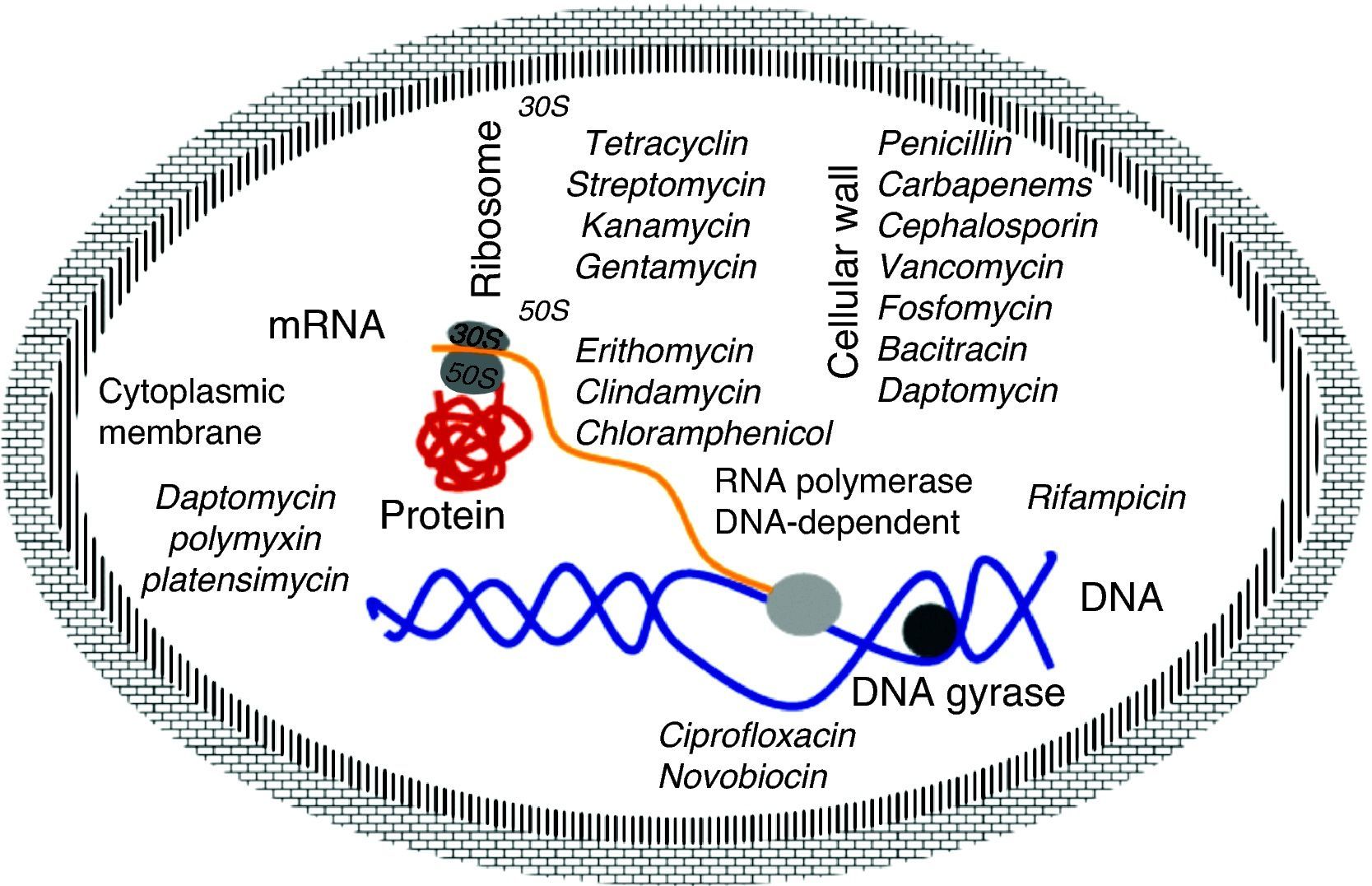

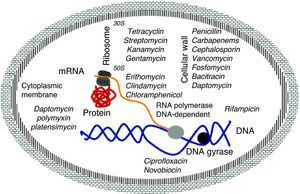

Mechanism of action of antibioticsThe molecular basis of this action is well understood and the main targets are well known. They are classified by the interaction of antibiotics targeting essential cellular functions, the fundamental principle to inhibit bacterial growth.17 This is a complex process that starts with the physical interaction of the molecule and its specific targets and involves biochemical, molecular, and structural changes, acting on multiple cellular targets such as: 1) DNA replication, 2) RNA synthesis, 3) cell wall synthesis, and 4) protein synthesis (Fig. 2).

DNA replicationDNA gyrase (topoisomerase) controls the topology of the DNA by catalyzing the cleavage pattern and DNA binding. This reaction is important for DNA synthesis and mRNA transcription, and the complex-quinolone topoisomerase-DNA cleavage prevents replication, leading to death of the bacteria.18–20

Synthesis of RNAThe DNA-dependent RNA polymerase mediates the transcription process and is the main regulator of gene expression in prokaryotes. The enzymatic process is essential for cell growth, making it an attractive target for antibiotics. One example is rifamycin, which inhibits the synthesis of RNA by using a stable connection with high affinity to the β-subunit in the RNA/DNA channel, separating the active site by inhibiting the initiation of transcription and blocking the path of ribonucleotide chain growth.18–20

Cell wall synthesisThe bacterial cell wall consists of peptidoglycan, which helps maintain the osmotic pressure, conferring ability to survive in diverse environments. The peptidoglycan biosynthesis involves three stages: the first stage occurs in the cytoplasm, where low molecular weight precursors are synthesized. In the second stage, the cell wall synthesis is catalyzed by membrane-bound enzymes; and in the third stage the antibiotic acts by preventing the β-lactams and polymerization of the glycan synthesis of cell wall enzymes, acting on transpetidades.18–20

Protein synthesisThe translation process of mRNA occurs in three phases: initiation, elongation, and termination involving cytoplasmic ribosomes and other components. The ribosome is composed of two subunits (50S and 30S), which are targets of the main antibiotic that inhibits protein synthesis. Macrolides act by blocking the 50S subunit, preventing the formation of the peptide chain: tetracycline in the 30S subunit acts by blocking the access of the aminoacyl tRNA-ribosome; spectinomycin interferes with the stability of the peptidyl-tRNA binding to the ribosome; and streptomycin, kanamycin, and gentamicin act in the 16S rRNA that is part of the 30S ribosome subunit.18–20

Cytoplasmic membraneThe cytoplasmic membrane acts as a diffusion barrier to water, ions, and nutrients. The transport systems are composed primarily of lipids, proteins, and lipoproteins. Daptomycin inserts into the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria in a calcium-dependent fashion, forming ion channels, triggering the release of intracellular potassium. Several antibiotics can cause disruption of the membrane. These agents can be divided into cationic, anionic, and neutral agents. The best known compounds are polymyxin B and colistemethate (polymyxin E). The polymyxins are not widely used because they are toxic to the kidney and to the nervous system.18–20 The latest antibiotic launched in 2006 by Merck (platensimycin) has different mechanism of action from the previous ones, since it acts by inhibiting the beta-ketoacyl synthases I / II (FabF / B), which are key enzymes in the production of fatty acids, necessary for bacterial cell membrane.13

ResistanceAccording to Nikaido20 100,000 tons of antibiotics are produced annually, which are used in agriculture, food, and health. Their use has impacted populations of bacteria, inducing antibiotics resistance. This resistance may be due to genetic changes such as mutation or acquisition of resistance genes through horizontal transfer, which most often occurs in organisms of different taxonomy.21,22 Mutations can cause changes at the site of drug action, hindering the action of the antibiotic.23 Most of the resistance genes are in the same cluster as the antibiotic biosynthesis gene.24 In nature, the main function of antibiotics is to inhibit competitors, which are induced to inactivate these compounds by chemical modification (hydrolysis), and changes in the site of action and membrane permeability.25 A study carried out with Streptomyces from urban soil showed that most strains are resistant to multiple antibiotics, suggesting that these genes are frequent in this environment.20 Many resistance genes are located on plasmids (plasmid A), which can be passed by conjugation to a susceptible strain; these plasmids are stable and can express the resistance gene.26 The susceptibility to a particular antibiotic can be affected by the physiological state of the bacteria, and the concentration of the antibiotic; this may be observed in biofilms through a mechanism known as persister formation - small subpopulations of bacteria survive the lethal concentration of antibiotic without any specific resistance mechanisms, although this mechanism does not produce high-level resistance.27

Microorganisms growing in a biofilm are associated with chronic and recurrent human infections and are resistant to antimicrobial agents.28 The spread of resistant strains is not only linked to antibiotic use, but also to the migration of people, who disperse resistant strains among people in remote communities where the use of antibiotics is very limited.24 Due to the difficulty of obtaining new antibiotics, the drug industry has made changes to existing antibiotics; these semi-synthetics are more efficient and less susceptible to inactivation by enzymes that cause resistance. This practice has become the strategy for the current antibiotics used today and is known as the second, third, and fourth generation of antibiotics.29,30

Genome and new antibioticsWith the availability of genomes from a large number of pathogens, hundreds of genes have been evaluated as targets for new antibiotics. A gene is recognized as essential when the bacterium can not survive while the gene is inactive, and can become a target when a small molecule can alter its activity.31 Genetic analysis has shown that a gene may encode a function that is important in one bacteria but not in another.32 167 genes have been determined as essential for bacterial growth and are potential targets for new antibiotics.33,34 GlaxoSmithKline has conducted studies with the antibiotic GKS299423 acting on topoisomerase II, in order to prevent the bacteria from developing resistance.35

UseThe world's demand for antibacterials (antibiotics) is steadily growing. Since their discovery in the 20th century, antibiotics have substantially reduced the threat of infectious diseases. The use of these “miracle drugs”, combined with improvements in sanitation, housing, food, and the advent of mass immunization programs, led to a dramatic drop in deaths from diseases that were once widespread and often fatal. Over the years, antibiotics have saved lives and eased the suffering of millions. By keeping many serious infectious diseases under control, these drugs also contributed to the increase in life expectancy during the latter part of the 20th century.

The increasing resistance of pathogenic organisms, leading to severe forms of infection that are difficult to treat, has further complicated the situation, as in the case of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae,36,37 and other microorganisms.38 Infections caused by resistant bacteria do not respond to treatment, resulting in prolonged illness and greater risk of death. Treatment failures also lead to long periods of infectivity with high rates of resistance, which increase the number of infected people circulating in the community and thus expose the population to the risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant strain.39

As bacteria become resistant to first generation antibiotics, treatment has to be changed to second or third generation drugs, which are often much more expensive and sometimes toxic. For example, the drug needed to treat multi-drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, can cost 100 times more than first generation drugs used to treat non-resistant forms. Most worrisome is that resistance to virtually all antibiotics has increased.

Even though the pharmaceutical industry has intensified efforts to develop new drugs to replace those in use, current trends suggest that some infections will have no effective therapies within the next ten years. The use of antibiotics is the critical factor in the selection of resistance.40,41 Paradoxically, underuse through lack of access and inadequate treatment may play a role as important as overuse. For these reasons, proper use is a priority to prevent the emergence and spread of bacterial resistance. Patient-related factors are the main causes of inappropriate use of antibiotics. For example, many patients believe that new and expensive drugs are more effective than older drugs.

In addition to causing unnecessary expenditure, this perception encourages the selection of resistance to these new drugs, as well as to the older drugs in their class.42 Self-medication with antibiotics is another important factor that contributes to resistance, because patients may not take adequate amounts of the drug. In many developing countries, antibiotics are purchased in single doses and taken only until the patient feels better, which may occur before the bacteria is eliminated.43

Physicians can be pressured to prescribe antibiotics to meet patient expectations, even in the absence of appropriate indications, or by manufacturers’ influence. Some doctors tend to prescribe antibiotics to cure viral infections, making them ineffective against other infections. In some cultural contexts, antibiotics administered by injection are considered more effective than oral formulations. Hospitals are a critical component of the problem of antimicrobial resistance worldwide.14,44 The combination of highly susceptible patients, patients with serious infections, and intense and prolonged use of antibiotics has resulted in highly resistant nosocomial infections, which are difficult to control, making eradication of the pathogen expensive.

In September 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the first global strategy to combat the serious problems caused by the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Known as the WHO Global Strategy for the Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance,45 the strategy recognizes that antimicrobial resistance is a global problem that must be addressed in all countries. No nation, however effective, can close its border to resistant bacteria, thus proper control is required in all places. Much of the responsibility lies with national governments, with a strategy and particular attention to interventions that involve the introduction of legislation and policies governing the development, licensing, distribution, and sale of antibiotics.46

Finding new antibiotics that are effective against bacterial resistance is not impossible, but it is a complex and challenging area of research. It is also an area that has not been the primary focus of the pharmaceutical industry in recent years, because antibiotics generally represent a relatively low return of investment, and the high standards for drug development are also factors that influence this lack of interest.

Despite the expected growth trends for the global market of antibiotics, their long-term success is primarily influenced by two main factors - resistance and generic competition. Antibiotic resistance forces reduction in use. The increase in antibiotic resistance makes curing infections difficult. A major disadvantage is the difficulty of the industry to find new antibiotics - those in use are generally ongoing modifications to produce new forms. Despite the advantages large companies have in the development of new antibiotics: a) well-defined targets, b) mode of research effectively established, c) biomarkers for monitoring, d) sophisticated tools to study dosing, and e) faster approval by regulatory agencies, they have given priority to other diseases, because the return on investment for antibiotics is low, despite representing a market of $ 45 billion, second only to drugs for cardiovascular problems and central nervous system.47 Another problem is competition from generics at far lower prices.48 In some cases the large companies have transferred the responsibility to small businesses to develop new antibiotics, such as daptomycin, developed by Cubist and licensed to Lilly.49

PerspectivesDespite this scenario, some companies have established a social position and responsibility to maintain the development of new antibiotics. An example is the potential for such partnerships in the fight against tuberculosis (TB). Today, multidrug resistant TB affects half a million people annually, takes two years to treat, is cured in only half of the cases, and occurs mainly in areas where the human development index is low.

To accelerate the development of new treatments, an important collaboration, the TB Alliance, is exploring creative funding mechanisms and support for the final phase of clinical trials. Another important action is the collection of microorganisms in different environments, such as marine environments, for the isolation of new substances; these studies have achieved important results evaluating these environment actinomycetes.30,50 Another initiative is the Amazon Biotechnology Center-CBA, that has been studying microorganisms in the Amazon region, since this region, with its high diversity of microorganisms, has the capacity to produce new antibiotics; excellent results have been achieved mainly regarding Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

There is still a need for regulation of the use of antibiotics to encourage pharmaceutical companies to invest in developing new antibiotics. The main challenge remains at the regulatory level, in order to find a solution that ensures the commercial viability of antibiotic development. The merger of these companies has an immediate impact, reducing the number of competing research and development groups; such changes often cause a strategic review of the therapeutic areas of research and development, where development of new antibiotics must compete with other areas that may be more commercially attractive.

In contrast to the first antibiotic, where the molecular mode of action was unknown until after it was introduced into the market, technologies have evolved (functional genomics), allowing the evaluation of the interaction between the mechanism of action of the antibiotic target and the development of specific resistance of the bacteria.51,52 Despite the sequencing projects of pathogenic organisms and the study of new targets, little success has been achieved.53,54 From a technical perspective, companies that remain committed to research into new antibiotics using the new technologies will be successful; the challenges are great, but not insurmountable.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare to have no conflict of interest.