As part of the Assessing Worldwide Antimicrobial Resistance Evaluation (AWARE) surveillance program in 2012 the in vitro activity of ceftaroline and relevant comparator antimicrobials was evaluated in six Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela) against pathogens isolated from patients with hospital associated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). The study documented that ceftaroline was highly active (MIC90 0.25mg/L/% susceptible 100%) against methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MIC90 2mg/L/% susceptible 83.3%) and β-hemolytic streptococci (MIC90 0.008–0.015mg/L/% susceptible 100%). The activity of ceftaroline against selected species of Enterobacteriaceae was dependent upon the presence or absence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs). Against ESBL screen-negative Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Klebsiella oxytoca the MIC90 and percent susceptible for ceftaroline were (0.5mg/L/94.1%), (0.5mg/L/99.0%) and (0.5mg/L/91.5%), respectively. Ceftaroline demonstrated potent activity against a recent collection of pathogens associated with SSTI in six Latin American countries in 2012.

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) cover a broad range of infectious processes including wounds, abscesses, skin structure, cellulitis, erysipelas, furuncles, burns, carbuncles, impetigo, and a variety of animal bite infections.1 The successful management of both community-associated and hospital associated SSTI involves accurate diagnosis, source control, laboratory microbiological support, and as needed appropriate antimicrobial regimens either empirical or directed post culture and susceptibility testing.1–3

Irrespective of anatomical site, the bacterial etiology of SSTI most frequently involves two species of Gram-positive cocci namely Staphylococcus aureus and β-hemolytic streptococci as well as various members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and rarely anaerobes.4–6

Surgical drainage/debridement as well as antimicrobial therapy remains the mainstay of appropriate SSTI management. However, increasing global antimicrobial resistance in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens including those associated with SSTI has complicated both empirical and directed antimicrobial therapy.1 Prevalence studies have shown that over 50% of SSTI are caused by S. aureus including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) thus greatly reducing the inherent or preferred use of a β-lactam for potential S. aureus SSTI.7,8 The CDC considers MRSA a serious threat with over 80,000 severe MRSA infections per year and an unknown but much higher number of less severe infections including SSTI.9

Over the past 15 years antimicrobials with activity against MRSA including vancomycin, daptomycin, tigecycline, and linezolid have been available, but each of these has therapeutic limitations and may not on their own provide coverage of polymicrobial infections that include Gram-negative pathogens. In the face of increasing antimicrobial resistance the search for new antimicrobials with activity against a variety of pathogens has led to the development and marketing of ceftaroline fosamil, a new broad-spectrum parenteral cephalosporin. Ceftaroline, the active metabolite of ceftaroline fosamil, inhibits penicillin-binding protein 2a of MRSA and shows effective activity against MRSA as well as against other Gram-positive cocci, and several species of Enterobacteriaceae (excluding those that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases [ESBLs] or inducible AmpC β-lactamases).10,11 Prior in vitro susceptibility studies provide support of ceftaroline activity against many Gram-positive and commonly isolated Gram-negative pathogens.12–19

The AWARE (Assessing Worldwide Antimicrobial Resistance Evaluation) global surveillance program was established to monitor the susceptibility of pathogens to ceftaroline as well as relevant comparator antimicrobials to pathogens associated with SSTI as well as lower respiratory tract infection pathogens and complicated urinary tract infections in many areas of the world including Latin America. This report summarizes the data from SSTI pathogens from the AWARE program in Latin America in 2012.

Material and methodsBacterial isolatesA total of 1142 clinical isolates from patients with SSTI were collected from 17 medical centers in six Latin American countries in 2012: Argentina (three), Brazil (two), Chile (three), Columbia (two), Mexico (five), and Venezuela (two). All isolates were collected from patients presenting with SSTI. The AWARE surveillance program is not designed as a prevalence of infection study as each participating laboratory was asked to collect and submit a defined number of specific pathogens from SSTI (one isolate per patient infection episode). All isolates were submitted to International Health Management Associates Inc. (Schaumburg, IL, USA). Organism identification was confirmed using a Bruker Biotyper MALDI-TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testingMinimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by the broth microdilution method recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) performance standard.20 Susceptibility was determined according to interpretive criteria set by the CLSI or FDA as appropriate.21,22 Breakpoints for ceftaroline have been recommended for S. aureus (≤1mg/L, susceptible), streptococci, and Enterobacteriaceae (≤0.5mg/L, susceptible) by the CLSI. All MIC panels were prepared at IHMA and frozen at −80°C prior to usage. MICs were entered into a central database and only accepted if quality control values using appropriate American Type Culture Collection control strains were within acceptable ranges. ESBL phenotypic activity was determined by screening Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Proteus mirabilis with ceftazidime and aztreonam according to CLSI guidelines.21 ESBL screen-positive was defined as any E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, or P. mirabilis isolate with either ceftazidime or aztreonam MIC values of >1mg/L. All other E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, or P. mirabilis isolates were designated as ESBL screen-negative.

Results and discussionIn 2012 the 17 participating medical centers in Latin America contributed 1142 clinical isolates. The majority of isolates, both Gram-positive and Gram-negative, came from four main infection sources: wound (44%), abscess (26%), cellulitis (10%), and skin ulcers (9%). All other infection sites contributed ≤4% of isolates.

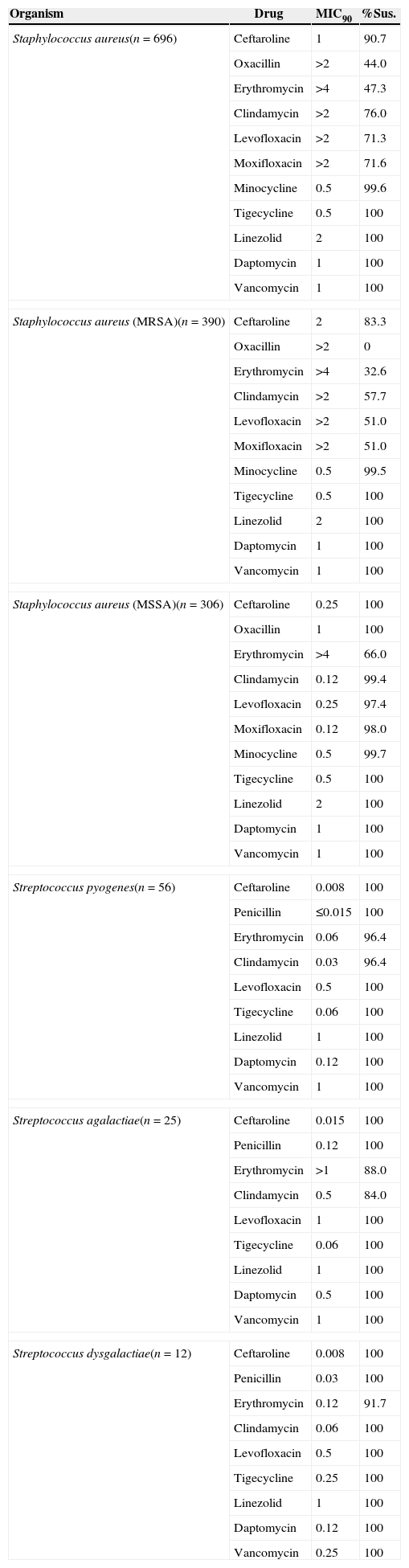

The susceptibility of various Gram-positive cocci to ceftaroline and relevant comparators is provided in Table 1. Against 696 S. aureus isolates (methicillin susceptible [MSSA] and MRSA isolates combined) the ceftaroline MIC90 was 1mg/L with 90.7% of all isolates susceptible. Only tigecycline and minocycline demonstrated lower MIC90 values of 0.5mg/L. S. aureus isolates irrespective of methicillin phenotype were susceptible to daptomycin, linezolid, tigecycline, and vancomycin. 100% of MSSA were susceptible to ceftaroline with an MIC90 of 0.25mg/L and 83.3% of MRSA susceptible to ceftaroline with MIC90 of 2mg/L. No MRSA were identified with an MIC >2mg/L (Table 1).

In vitro activity of ceftaroline against key Gram-positive pathogens in SSTI from Latin America, 2012.

| Organism | Drug | MIC90 | %Sus. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus(n=696) | Ceftaroline | 1 | 90.7 |

| Oxacillin | >2 | 44.0 | |

| Erythromycin | >4 | 47.3 | |

| Clindamycin | >2 | 76.0 | |

| Levofloxacin | >2 | 71.3 | |

| Moxifloxacin | >2 | 71.6 | |

| Minocycline | 0.5 | 99.6 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Linezolid | 2 | 100 | |

| Daptomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)(n=390) | Ceftaroline | 2 | 83.3 |

| Oxacillin | >2 | 0 | |

| Erythromycin | >4 | 32.6 | |

| Clindamycin | >2 | 57.7 | |

| Levofloxacin | >2 | 51.0 | |

| Moxifloxacin | >2 | 51.0 | |

| Minocycline | 0.5 | 99.5 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Linezolid | 2 | 100 | |

| Daptomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA)(n=306) | Ceftaroline | 0.25 | 100 |

| Oxacillin | 1 | 100 | |

| Erythromycin | >4 | 66.0 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.12 | 99.4 | |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 97.4 | |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.12 | 98.0 | |

| Minocycline | 0.5 | 99.7 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Linezolid | 2 | 100 | |

| Daptomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes(n=56) | Ceftaroline | 0.008 | 100 |

| Penicillin | ≤0.015 | 100 | |

| Erythromycin | 0.06 | 96.4 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.03 | 96.4 | |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.06 | 100 | |

| Linezolid | 1 | 100 | |

| Daptomycin | 0.12 | 100 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae(n=25) | Ceftaroline | 0.015 | 100 |

| Penicillin | 0.12 | 100 | |

| Erythromycin | >1 | 88.0 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.5 | 84.0 | |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 100 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.06 | 100 | |

| Linezolid | 1 | 100 | |

| Daptomycin | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 100 | |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae(n=12) | Ceftaroline | 0.008 | 100 |

| Penicillin | 0.03 | 100 | |

| Erythromycin | 0.12 | 91.7 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.06 | 100 | |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.25 | 100 | |

| Linezolid | 1 | 100 | |

| Daptomycin | 0.12 | 100 | |

| Vancomycin | 0.25 | 100 | |

CLSI susceptibilities defined by CLSI document M100-S24 (2014), where applicable; tigecycline susceptibilities under CLSI defined by FDA (2013).

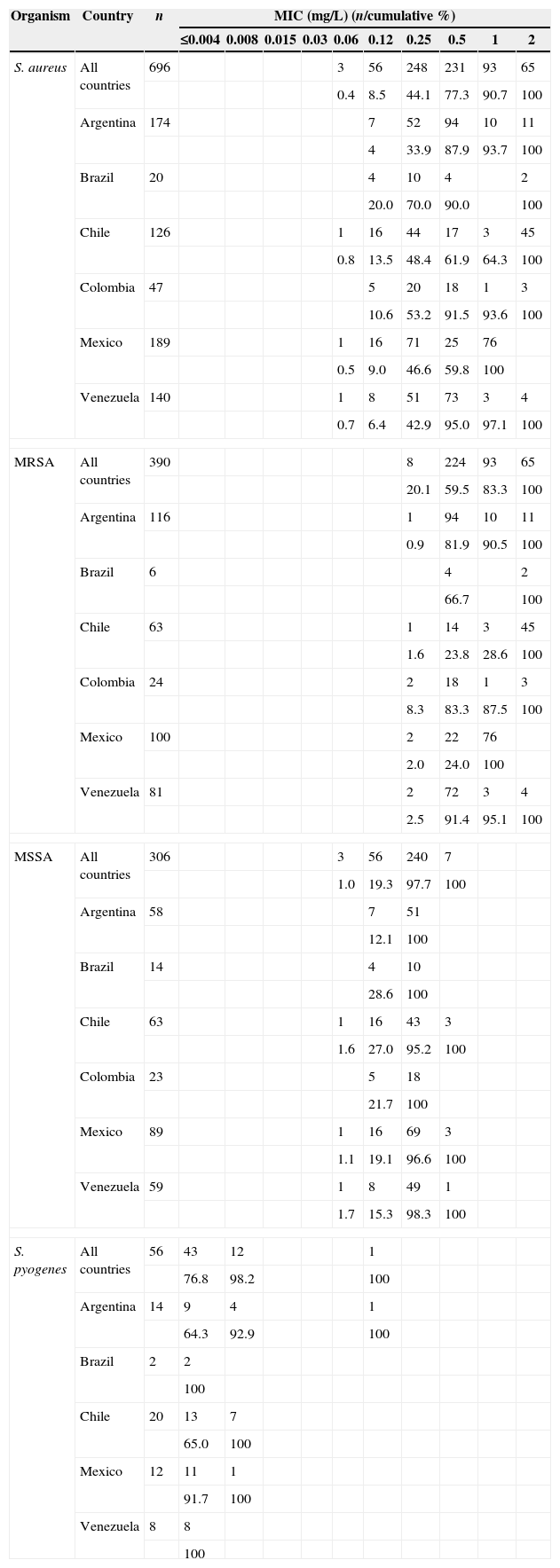

Variations in MIC90 for ceftaroline against MRSA were relatively minor with ranges from 0.5mg/L in isolates from Venezuela to 2mg/L in isolates from Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. Ceftaroline MICs for MSSA isolates displayed minimal variation (0.06–0.5mg/L) with MIC90 of 0.25mg/L irrespective of country (Table 2). All β-hemolytic streptococci (Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, and Streptococcus pyogenes) were susceptible to ceftaroline with MIC90 ranges of 0.008–0.015mg/L (Table 1) with 55/56 S. pyogenes ceftaroline MIC90 of ≤0.008mg/L in all countries studied (Table 2). Isolates were 100 percent susceptible to most comparators with the exception of clindamycin and erythromycin where susceptibility ranged from 84.0 to 96.4%.

Frequency distribution of ceftaroline against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes in SSTI from Latin America, 2012.

| Organism | Country | n | MIC (mg/L) (n/cumulative %) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.004 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | |||

| S. aureus | All countries | 696 | 3 | 56 | 248 | 231 | 93 | 65 | ||||

| 0.4 | 8.5 | 44.1 | 77.3 | 90.7 | 100 | |||||||

| Argentina | 174 | 7 | 52 | 94 | 10 | 11 | ||||||

| 4 | 33.9 | 87.9 | 93.7 | 100 | ||||||||

| Brazil | 20 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 2 | |||||||

| 20.0 | 70.0 | 90.0 | 100 | |||||||||

| Chile | 126 | 1 | 16 | 44 | 17 | 3 | 45 | |||||

| 0.8 | 13.5 | 48.4 | 61.9 | 64.3 | 100 | |||||||

| Colombia | 47 | 5 | 20 | 18 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| 10.6 | 53.2 | 91.5 | 93.6 | 100 | ||||||||

| Mexico | 189 | 1 | 16 | 71 | 25 | 76 | ||||||

| 0.5 | 9.0 | 46.6 | 59.8 | 100 | ||||||||

| Venezuela | 140 | 1 | 8 | 51 | 73 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 0.7 | 6.4 | 42.9 | 95.0 | 97.1 | 100 | |||||||

| MRSA | All countries | 390 | 8 | 224 | 93 | 65 | ||||||

| 20.1 | 59.5 | 83.3 | 100 | |||||||||

| Argentina | 116 | 1 | 94 | 10 | 11 | |||||||

| 0.9 | 81.9 | 90.5 | 100 | |||||||||

| Brazil | 6 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||

| 66.7 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Chile | 63 | 1 | 14 | 3 | 45 | |||||||

| 1.6 | 23.8 | 28.6 | 100 | |||||||||

| Colombia | 24 | 2 | 18 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| 8.3 | 83.3 | 87.5 | 100 | |||||||||

| Mexico | 100 | 2 | 22 | 76 | ||||||||

| 2.0 | 24.0 | 100 | ||||||||||

| Venezuela | 81 | 2 | 72 | 3 | 4 | |||||||

| 2.5 | 91.4 | 95.1 | 100 | |||||||||

| MSSA | All countries | 306 | 3 | 56 | 240 | 7 | ||||||

| 1.0 | 19.3 | 97.7 | 100 | |||||||||

| Argentina | 58 | 7 | 51 | |||||||||

| 12.1 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Brazil | 14 | 4 | 10 | |||||||||

| 28.6 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Chile | 63 | 1 | 16 | 43 | 3 | |||||||

| 1.6 | 27.0 | 95.2 | 100 | |||||||||

| Colombia | 23 | 5 | 18 | |||||||||

| 21.7 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Mexico | 89 | 1 | 16 | 69 | 3 | |||||||

| 1.1 | 19.1 | 96.6 | 100 | |||||||||

| Venezuela | 59 | 1 | 8 | 49 | 1 | |||||||

| 1.7 | 15.3 | 98.3 | 100 | |||||||||

| S. pyogenes | All countries | 56 | 43 | 12 | 1 | |||||||

| 76.8 | 98.2 | 100 | ||||||||||

| Argentina | 14 | 9 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| 64.3 | 92.9 | 100 | ||||||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 100 | ||||||||||||

| Chile | 20 | 13 | 7 | |||||||||

| 65.0 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Mexico | 12 | 11 | 1 | |||||||||

| 91.7 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Venezuela | 8 | 8 | ||||||||||

| 100 | ||||||||||||

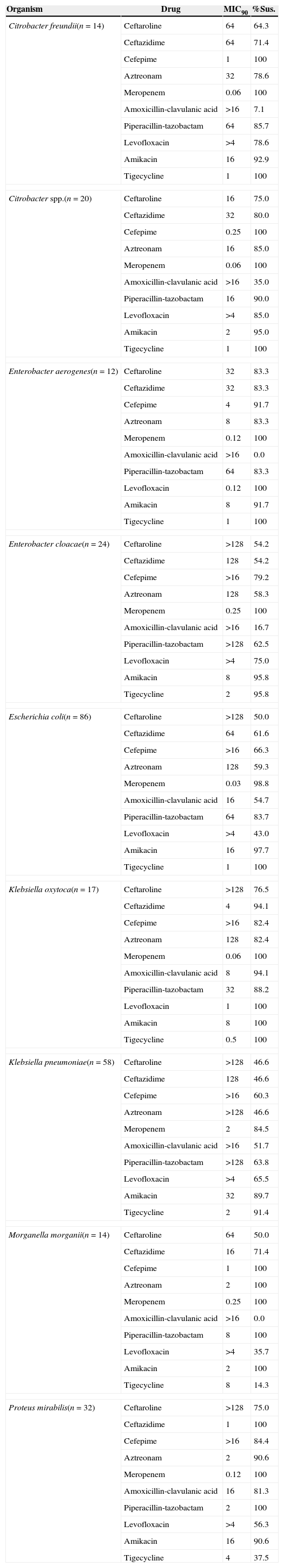

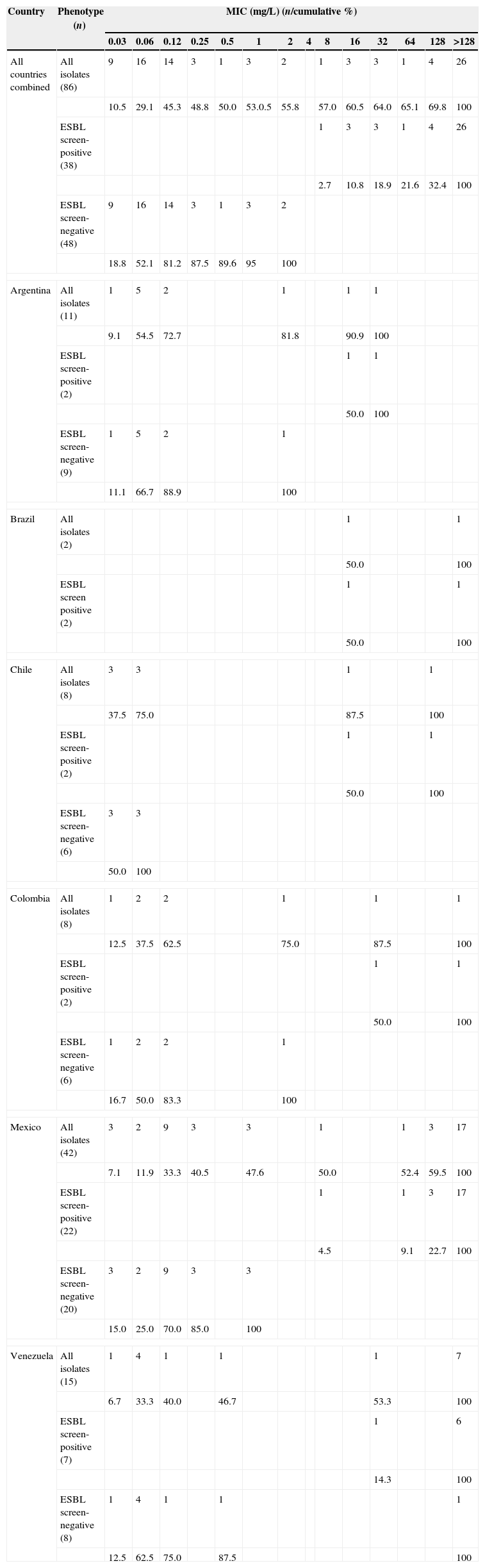

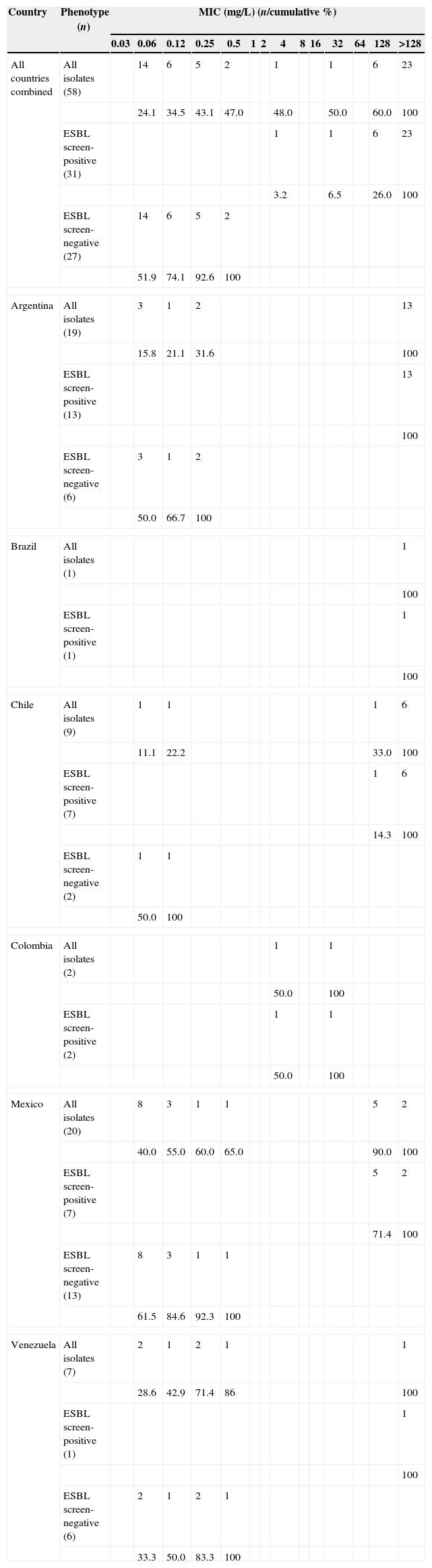

The activity of ceftaroline and comparators is shown in Table 3 for relevant Gram-negative bacilli where n>10. MIC90/% susceptible for ceftaroline by species were: Citrobacter freundii (64/64.3%), Citrobacter spp. (16/75%), Enterobacter aerogenes (32/83.3%), Enterobacter cloacae (>128/54.2%), E. coli (>128/50.0%), K. oxytoca (>128/76.5%), K. pneumoniae (>128/46.6%), Morganella morganii (64/50.0%), and Proteus mirabilis (>128/75%). For most Gram-negative bacilli examined tigecycline, piperacillin-tazobactam, amikacin, and meropenem displayed the highest percent susceptible ranging from 91 to 100% susceptible with the exception of K. pneumoniae. The MIC frequency distributions of ceftaroline against both ESBL screen-positive and ESBL screen-negative E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and K. oxytoca are shown in Tables 4–5. For all six Latin American countries combined the ceftaroline MIC90 was >128mg/L for all 86 E. coli with 50% of isolates susceptible at the CLSI breakpoint of 0.5mg/L (Table 4). Ceftaroline was not active against ESBL screen-positive E. coli isolates with all isolates demonstrating MICs ≥8mg/L. However for ESBL screen-negative isolates the MIC90 was 0.5mg/L with 95% of isolates susceptible. Two ESBL screen-negative E. coli isolates (one each from Argentina and Colombia) were resistant to ceftaroline with MICs of 2mg/L. The MIC frequency distribution of ceftaroline against 58 K. pneumoniae from all Latin American countries is shown in Table 5. MIC90 values were >128mg/L with only 48% of isolates susceptible at the CLSI breakpoint of 0.5mg/L. All 31 ESBL screen positive isolates were resistant to ceftaroline, whereas all ESBL screen-negative isolates were fully susceptible to ceftaroline. The MIC90 of ceftaroline for all Latin American K. oxytoca isolates (17) was >128mg/L with 76.5% susceptible at 0.5mg/L (data not shown). Only three ESBL screen-positive isolates were identified from this region: Chile (one) and Venezuela (two) with MIC values of >128mg/L. For the ESBL screen-negative isolates the MIC90 was 0.5mg/L with only one isolate from Argentina for which the ceftaroline MIC was 4mg/L.

In vitro activity of ceftaroline against key Gram-negative pathogens in SSTI from Latin America, 2012.

| Organism | Drug | MIC90 | %Sus. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrobacter freundii(n=14) | Ceftaroline | 64 | 64.3 |

| Ceftazidime | 64 | 71.4 | |

| Cefepime | 1 | 100 | |

| Aztreonam | 32 | 78.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | >16 | 7.1 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 64 | 85.7 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 78.6 | |

| Amikacin | 16 | 92.9 | |

| Tigecycline | 1 | 100 | |

| Citrobacter spp.(n=20) | Ceftaroline | 16 | 75.0 |

| Ceftazidime | 32 | 80.0 | |

| Cefepime | 0.25 | 100 | |

| Aztreonam | 16 | 85.0 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | >16 | 35.0 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 16 | 90.0 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 85.0 | |

| Amikacin | 2 | 95.0 | |

| Tigecycline | 1 | 100 | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes(n=12) | Ceftaroline | 32 | 83.3 |

| Ceftazidime | 32 | 83.3 | |

| Cefepime | 4 | 91.7 | |

| Aztreonam | 8 | 83.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | >16 | 0.0 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 64 | 83.3 | |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12 | 100 | |

| Amikacin | 8 | 91.7 | |

| Tigecycline | 1 | 100 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae(n=24) | Ceftaroline | >128 | 54.2 |

| Ceftazidime | 128 | 54.2 | |

| Cefepime | >16 | 79.2 | |

| Aztreonam | 128 | 58.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.25 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | >16 | 16.7 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | >128 | 62.5 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 75.0 | |

| Amikacin | 8 | 95.8 | |

| Tigecycline | 2 | 95.8 | |

| Escherichia coli(n=86) | Ceftaroline | >128 | 50.0 |

| Ceftazidime | 64 | 61.6 | |

| Cefepime | >16 | 66.3 | |

| Aztreonam | 128 | 59.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 98.8 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 16 | 54.7 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 64 | 83.7 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 43.0 | |

| Amikacin | 16 | 97.7 | |

| Tigecycline | 1 | 100 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca(n=17) | Ceftaroline | >128 | 76.5 |

| Ceftazidime | 4 | 94.1 | |

| Cefepime | >16 | 82.4 | |

| Aztreonam | 128 | 82.4 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 8 | 94.1 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 32 | 88.2 | |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 100 | |

| Amikacin | 8 | 100 | |

| Tigecycline | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae(n=58) | Ceftaroline | >128 | 46.6 |

| Ceftazidime | 128 | 46.6 | |

| Cefepime | >16 | 60.3 | |

| Aztreonam | >128 | 46.6 | |

| Meropenem | 2 | 84.5 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | >16 | 51.7 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | >128 | 63.8 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 65.5 | |

| Amikacin | 32 | 89.7 | |

| Tigecycline | 2 | 91.4 | |

| Morganella morganii(n=14) | Ceftaroline | 64 | 50.0 |

| Ceftazidime | 16 | 71.4 | |

| Cefepime | 1 | 100 | |

| Aztreonam | 2 | 100 | |

| Meropenem | 0.25 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | >16 | 0.0 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 8 | 100 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 35.7 | |

| Amikacin | 2 | 100 | |

| Tigecycline | 8 | 14.3 | |

| Proteus mirabilis(n=32) | Ceftaroline | >128 | 75.0 |

| Ceftazidime | 1 | 100 | |

| Cefepime | >16 | 84.4 | |

| Aztreonam | 2 | 90.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | 100 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 16 | 81.3 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 2 | 100 | |

| Levofloxacin | >4 | 56.3 | |

| Amikacin | 16 | 90.6 | |

| Tigecycline | 4 | 37.5 | |

CLSI susceptibilities defined by CLSI document M100-S24 (2014), where applicable; tigecycline susceptibilities under CLSI defined by FDA (2013).

Frequency distribution (n) and cumulative percent inhibited (%) at each MIC for ceftaroline against Escherichia coli and phenotypes in SSTI from Latin America, 2012.

| Country | Phenotype (n) | MIC (mg/L) (n/cumulative %) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | >128 | ||

| All countries combined | All isolates (86) | 9 | 16 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 26 | |

| 10.5 | 29.1 | 45.3 | 48.8 | 50.0 | 53.0.5 | 55.8 | 57.0 | 60.5 | 64.0 | 65.1 | 69.8 | 100 | |||

| ESBL screen-positive (38) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 26 | |||||||||

| 2.7 | 10.8 | 18.9 | 21.6 | 32.4 | 100 | ||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (48) | 9 | 16 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

| 18.8 | 52.1 | 81.2 | 87.5 | 89.6 | 95 | 100 | |||||||||

| Argentina | All isolates (11) | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 9.1 | 54.5 | 72.7 | 81.8 | 90.9 | 100 | ||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (9) | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 11.1 | 66.7 | 88.9 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| Brazil | All isolates (2) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen positive (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Chile | All isolates (8) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 37.5 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (6) | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Colombia | All isolates (8) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 12.5 | 37.5 | 62.5 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 100 | ||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (6) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 16.7 | 50.0 | 83.3 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| Mexico | All isolates (42) | 3 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 17 | |||||

| 7.1 | 11.9 | 33.3 | 40.5 | 47.6 | 50.0 | 52.4 | 59.5 | 100 | |||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (22) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 17 | |||||||||||

| 4.5 | 9.1 | 22.7 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (20) | 3 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 15.0 | 25.0 | 70.0 | 85.0 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Venezuela | All isolates (15) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6.7 | 33.3 | 40.0 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 100 | ||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (7) | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 14.3 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (8) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 12.5 | 62.5 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 100 | |||||||||||

Frequency distribution (n) and cumulative percent inhibited (%) at each MIC for ceftaroline against Klebsiella pneumoniae and phenotypes in SSTI from Latin America, 2012.

| Country | Phenotype (n) | MIC (mg/L) (n/cumulative %) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | >128 | ||

| All countries combined | All isolates (58) | 14 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 23 | ||||||

| 24.1 | 34.5 | 43.1 | 47.0 | 48.0 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 100 | ||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (31) | 1 | 1 | 6 | 23 | |||||||||||

| 3.2 | 6.5 | 26.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (27) | 14 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 51.9 | 74.1 | 92.6 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| Argentina | All isolates (19) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 13 | ||||||||||

| 15.8 | 21.1 | 31.6 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (13) | 13 | ||||||||||||||

| 100 | |||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (6) | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 66.7 | 100 | |||||||||||||

| Brazil | All isolates (1) | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 100 | |||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 100 | |||||||||||||||

| Chile | All isolates (9) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||

| 11.1 | 22.2 | 33.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (7) | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 14.3 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Colombia | All isolates (2) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 50.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Mexico | All isolates (20) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | ||||||||

| 40.0 | 55.0 | 60.0 | 65.0 | 90.0 | 100 | ||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (7) | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 71.4 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (13) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 61.5 | 84.6 | 92.3 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| Venezuela | All isolates (7) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 28.6 | 42.9 | 71.4 | 86 | 100 | |||||||||||

| ESBL screen-positive (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 100 | |||||||||||||||

| ESBL screen-negative (6) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 33.3 | 50.0 | 83.3 | 100 | ||||||||||||

All MSSA and all isolates of β-hemolytic streptococci in this study of SSTI major pathogens in Latin America were susceptible to ceftaroline (Table 1). This analysis confirms prior reports from Europe,15 Latin America,12,13 and the United States14 that include MSSA isolates not only from SSTI but lower respiratory tract infections. Of the MRSA isolates collected from SSTI in Latin America 9.3% were identified as ceftaroline intermediate (MIC 2mg/L) and none of MRSA isolates were ceftaroline resistant (MIC>2mg/L). The present study again demonstrated that whereas ceftaroline resistance in MRSA is uncommon geographical and regional variances can alter the overall susceptibility of MRSA to ceftaroline.12,19 Ceftaroline exhibited potent activity against ESBL screen-negative E. coli, K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca in the present study as has been previously shown in several surveillance studies in various geographical areas.12–18 However ceftaroline had minimal in vitro activity against ESBL screen-positive Enterobacteriaceae SSTI isolates studied in this 2012 surveillance study in Latin America. All surveillance studies have limitations including isolate collection and data analysis. The AWARE surveillance study is not a prevalence of infection study nor a direct marker of phenotype prevalence as pathogen collection is dictated by rigorous study protocols. However, organism identification and susceptibility testing and interpretation are rigorously followed with comprehensive quality control in place.

In conclusion ceftaroline has been shown in this study and in prior surveillance studies to exhibit potent activity against MSSA and as a β-lactam agent potent activity against MRSA as well as β-hemolytic streptococci and ESBL screen-negative E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and K. oxytoca. SSTI currently represents one of the most common community and hospital associated infections globally and the need for new antimicrobials with activity against the most common pathogens associated with SSTI will need to continue to evolve. Ceftaroline represents one such newer antimicrobial with documented in vitro activity against the critical SSTI pathogens tested in this study from Latin America.

Conflicts of interestThis study at IHMA was supported by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, which also included compensation fees for services in relation to preparing the manuscript. DJH, DJB, and DFS are employees of International Health Management Associates, Inc. None of the IHMA authors have personal financial interests in the sponsor of this paper (AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals). ER and JPI are employees of AstraZeneca.

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the clinical trial investigators, laboratory personnel, and all members of the AWARE program.