To describe the access to the interventions for the prevention of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) mother to child transmission and mother to child transmission rates in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, from 1999 to 2009.

MethodsThis is a retrospective cohort study. Prevention of HIV mother to child transmission interventions were accessed and mother to child transmission rates were calculated.

ResultsThe study population is young (median: 26 years; interquartile range: 22.0–31.0), with low monthly family income (40.4% up to one Brazilian minimum wage) and schooling (62.1% less than 8 years). Only 47.1% (n=469) knew the HIV status of their partner; of these women, 39.9% had an HIV-seronegative partner. Among the 1259 newborns evaluated, access to the antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum prevention of HIV mother to child transmission components occurred in 59.2%, 74.2%, and 97.5% respectively; 91.0% of the newborns were not breastfed. Overall 52.7% of the newborns have benefited from all the recommended interventions. In subsequent pregnancies (n=289), 67.8% of the newborns received the full package of interventions. The overall rate of HIV vertical transmission was 4.7% and the highest annual rate occurred in 2005 (7.4%), with no definite trend in the period.

ConclusionsAccess to the full package of interventions for the prevention of HIV vertical transmission was low, with no significant trend of improvement over the years. The vertical transmission rates observed were higher than those found in reference services in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro and in the richest regions of the country.

Brazil was the first developing country to implement a national program to prevent HIV mother to child transmission (PMTCT). HIV Counseling and testing, access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and infant formula to substitute breastfeeding have been universally provided free-of-charge. Although PMTCT is considered as a high priority by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (BMH), it remains a relevant problem in the country1 with a significant number of new pediatric cases continuing to occur annually.2 In Brazil, between 1980 and June 2011, 13,540 cases of vertical transmission were reported; from January 2010 to June 2011, 457 new cases were notified.2

In Brazil, initial studies showed a MTCT rate of 16%,3 but there has been a significant decrease over recent years. In a national multicenter study covering 2924 children,4 the MTCT rate was 8.6% in 2000 and 7.1% in 2001, with significant regional differences, with less antiretroviral use during pregnancy in the north and northeast regions leading to higher rates of transmission. Studies conducted in the recent years still show striking regional disparities, with MTCT rates of between 2.4% and 4.9% in the southern and southeast regions, the wealthiest parts of Brazil,5–8 and transmission rates as high as 9.1 and 9.9 in the northeast and northern regions.9–11

The shortcomings of the health system highly impact the success of interventions for MTCT12 and this is even more critical in developing countries. Barriers to the implementation of the several interventions that are part of the prevention package for HIV MTCT (MTCT) as well as the programmatic results obtained vary regionally across the country.8 Rio de Janeiro ranks second in the number of reported AIDS cases in Brazil.

Although it is located in one of the most industrialized regions of the country, a large disparity still exists between the rich areas and the poor peripheral regions surrounding the capital city. The highest incidence of AIDS cases in the state is found in a region called Baixada Fluminense, an impoverished area in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, inhabited by four million marginalized individuals who are plagued by violence, poverty, social injustice, and endemic and epidemic diseases. Baixada Fluminense integrates 13 municipalities of which Nova Iguaçu has the highest population density and territory.13 Among the 92,089 individuals diagnosed with AIDS in Rio de Janeiro State between 1982 and 2012, 18,903 were from Baixada Fluminense.14

This study describes the cascade of access to the recommended interventions for PMTCT and the rates of MTCT among HIV-infected pregnant women in a metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

MethodologyThe HIV Family Care Clinic (HHFCC) operates within Hospital Geral de Nova Iguaçu (HGNI), the largest public hospital in Baixada Fluminense. HHFCC is the main referral center for HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants and provides free access to antiretrovirals (ARVs) and services for the prevention of MTCT. Considering 0.59% the HIV prevalence among women between 15 and 49 years,15 rate that has been stable since 2004,2 and the number of stillbirths in 2011,16 we estimated approximately 1300 as the number of HIV pregnant women assisted in Rio de Janeiro in that year; among those, 165 (12.7%) received care in HHFCC-HGNI. A retrospective cohort of HIV-infected pregnant women and their newborns was established at the HHFCC-HGNI in collaboration with the Instituto de Pesquisa Clinica Evandro Chagas – IPEC, Fiocruz.

In the present study, all HIV-infected pregnant women and their newborns who received care at the HHFCC between 01/01/1999 and 31/12/2009 were included. Retrospective chart review using a structured case report form was conducted. The project was approved by the HGNI (CAAE: 0005.1.316.000-07) Ethics in Research Committee.

Study definitionsRecommended package of interventions for HIV PMTCT according to the timing of HIV diagnosis in the pregnant women:

- (a)

HIV diagnosis before and during pregnancy: antenatal antiretroviral therapy (ART)+intrapartum IV Zidovudine (ZDV)+ZDV syrup+formula for the newborn;

- (b)

HIV diagnosis at labor/delivery: intrapartum IV ZDV+ZDV syrup+formula for the newborn;

- (c)

HIV diagnosis during the immediate postpartum: ZDV syrup+formula for the newborn.

HIV-positive newborns were defined as follows: two positive HIV diagnostic tests (using either the quantification of plasma HIV RNA (HIV viral load) or detection of proviral DNA) performed between 1 and 6 months of age, with one of them sampled after 4 months of age. For those children without a defined diagnosis who were over 18 months of age, two positive serology samples for anti-HIV-1 and -2 or two positive rapid tests using different methodologies were required.17,18

HIV-negative newborns were defined as follows: two negative HIV diagnostic tests (using either the quantification of plasma HIV viral load or the detection of proviral DNA) were performed between 1 and 6 months of age, with one of them sampled after 4 months of age, plus a non-reactive anti-HIV serology test after 12 months of age. For those children without a defined diagnosis who were over 18 months of age, a nonreactive HIV serology or a negative result using two rapid tests was required. In discordant cases, a third test was considered to reach a diagnostic conclusion.18

HIV-inconclusive newborns were defined as follows: children who did not have one of above definitions were considered as inconclusive for HIV serostatus, and the reason may be attributed to lost to follow-up or incomplete information in medical charts.

CD4+ lymphocyte count at enrolment (cells/mm3): the first result obtained at the entry in the cohort.

Skin color: this was obtained from chart review and was attributed by health professionals.

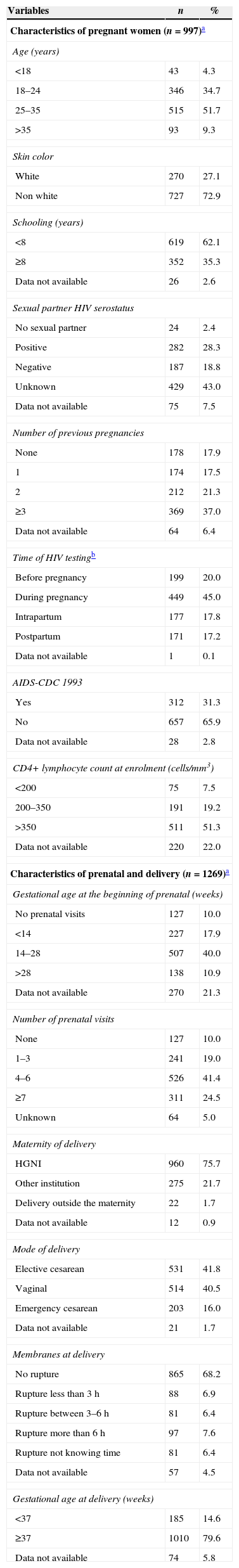

Statistical analysesFrequency, mean, standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe the socio-demographic, behavioral and reproductive characteristics, as well as those related to HIV/AIDS infection of women at entry in the cohort (n=997) and also to describe the characteristics of the pregnancies which resulted in delivery in the cohort (n=1269) between January 1999 and December 2009.

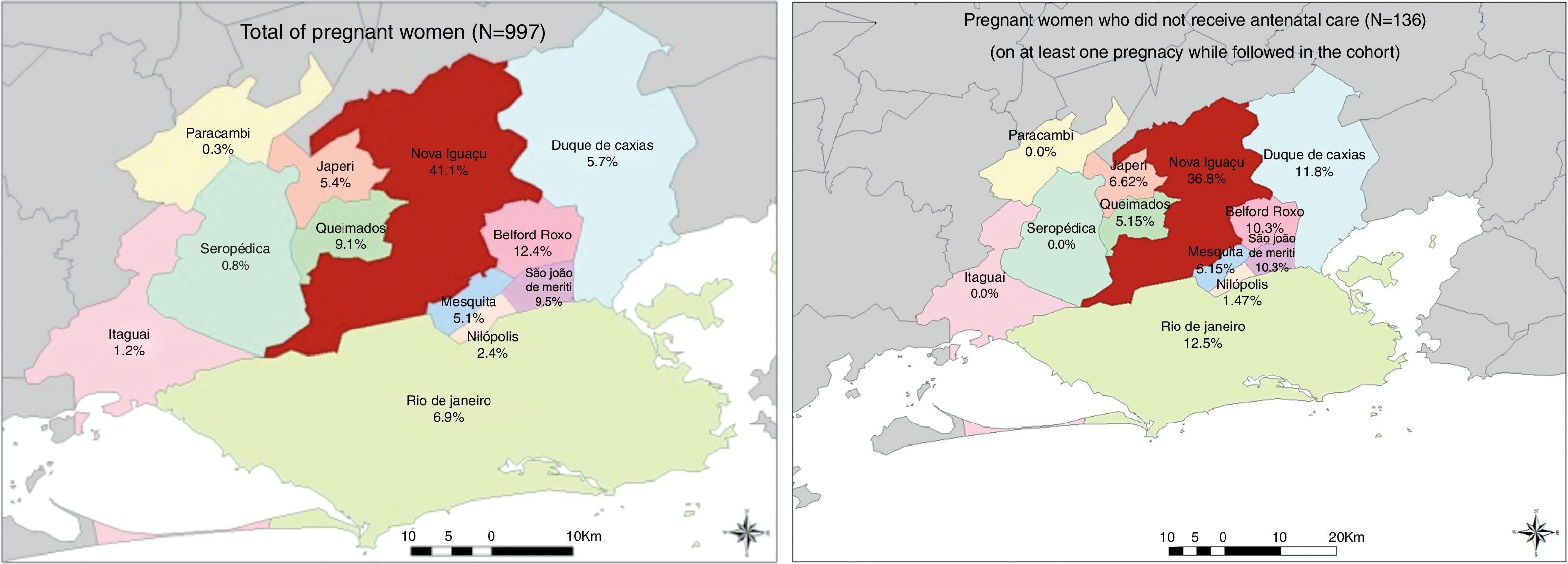

We described the municipality of residence for all women included in the study and for the subgroup of women who did not receive prenatal care using maps generated by ESRI 2011 software program only for illustrative purpose.19

Descriptive statistics were used to describe access to prophylactic interventions to reduce the risk of perinatal HIV transmission in this population, according to the moment of maternal mother HIV diagnosis. Trend analysis was carried out in order to evaluate the access to recommended package of interventions according to the moment of maternal mother HIV diagnosis over time. The overall and annual rates of perinatal HIV transmission were also calculated.

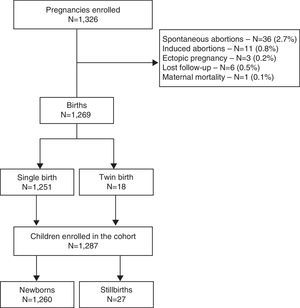

ResultsOverall, 997 women were included in the cohort with a total of 1326 pregnancies during the study period (1999–2009): 747 of the women had only one pregnancy, 188 had two pregnancies, 46 had three pregnancies, 15 had four pregnancies and one had five pregnancies. In total, 329 subsequent pregnancies were observed among 250 women, of which 289 resulted in live-birth infants.

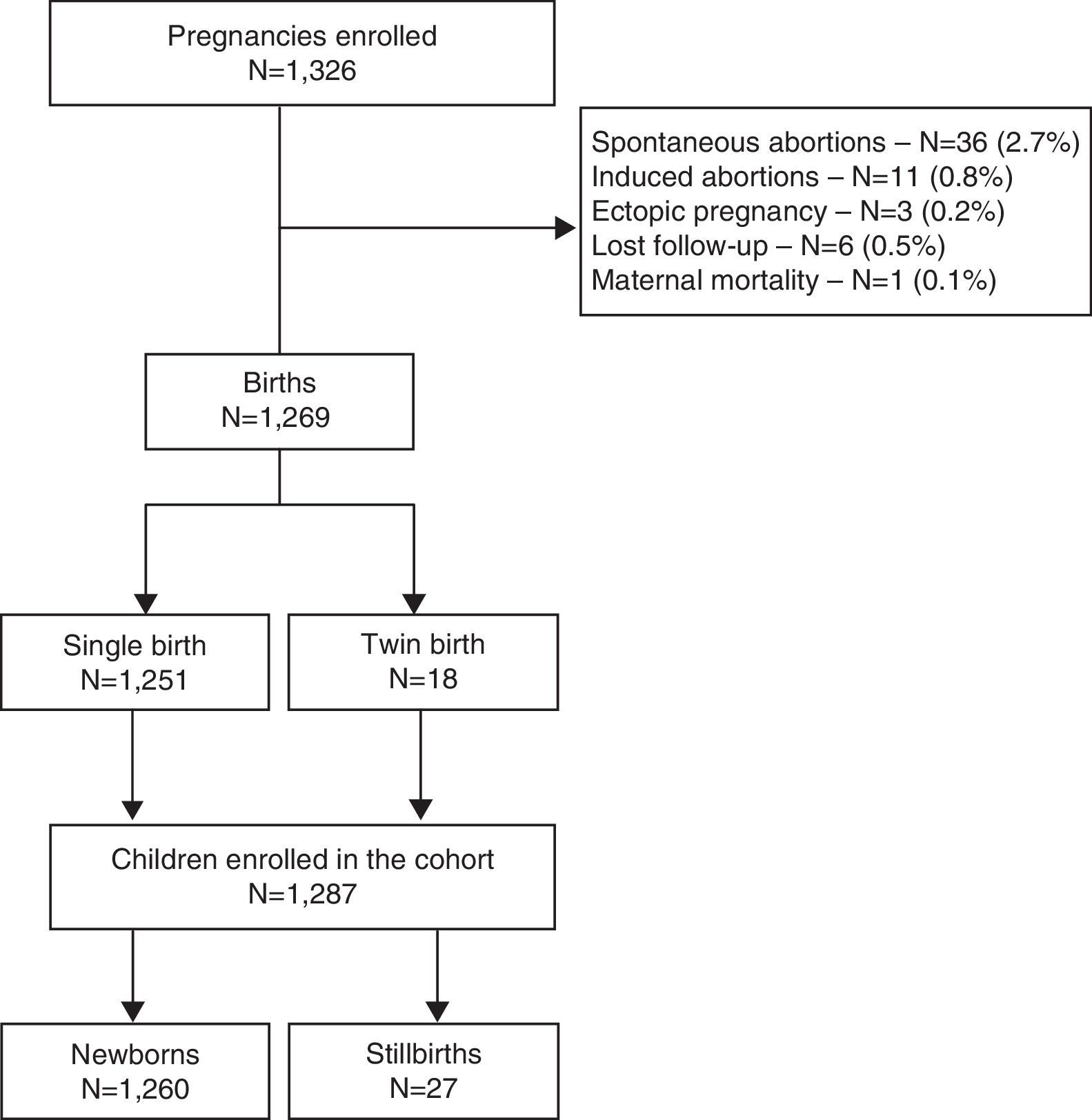

Of all 1326 pregnancies observed in the cohort, 1269 (95.7%) resulted in delivery. Eighteen deliveries were twins, resulting in a total of 1287 newborns. Of these, 97.9% (n=1260) were live-birth infants for whom the cascade of PMTCT interventions was evaluated. Loss to follow-up during the antenatal care period occurred in 0.5% of all the pregnancies (Fig. 1).

The characteristics of all women (n=997) at the entry in the cohort are presented in Table 1. The majority of them resided in the municipality of Nova Iguaçu (41.1%), where HHFCC is located, followed by the municipalities of Belford Roxo (12.4%), São João de Meriti (9.5%), Queimados (9.1%), Rio de Janeiro (6.9%) and Duque de Caxias (5.7%) (Fig. 2). The median age was 26 years (IQR: 22.0–31.0); 39% of the women were younger than 24 years of age, 72.9% were non-white (Table 1). Approximately 62% of them had less than 8 years of schooling, and 40.4% had a family income of up to one Brazilian minimum wage (varied from U$70.58 to U$234.46 during the study period).

Sociodemographic, clinical and obstetric characteristics of women and pregnancies included in the study, 1999–2009.

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of pregnant women (n=997)a | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| <18 | 43 | 4.3 |

| 18–24 | 346 | 34.7 |

| 25–35 | 515 | 51.7 |

| >35 | 93 | 9.3 |

| Skin color | ||

| White | 270 | 27.1 |

| Non white | 727 | 72.9 |

| Schooling (years) | ||

| <8 | 619 | 62.1 |

| ≥8 | 352 | 35.3 |

| Data not available | 26 | 2.6 |

| Sexual partner HIV serostatus | ||

| No sexual partner | 24 | 2.4 |

| Positive | 282 | 28.3 |

| Negative | 187 | 18.8 |

| Unknown | 429 | 43.0 |

| Data not available | 75 | 7.5 |

| Number of previous pregnancies | ||

| None | 178 | 17.9 |

| 1 | 174 | 17.5 |

| 2 | 212 | 21.3 |

| ≥3 | 369 | 37.0 |

| Data not available | 64 | 6.4 |

| Time of HIV testingb | ||

| Before pregnancy | 199 | 20.0 |

| During pregnancy | 449 | 45.0 |

| Intrapartum | 177 | 17.8 |

| Postpartum | 171 | 17.2 |

| Data not available | 1 | 0.1 |

| AIDS-CDC 1993 | ||

| Yes | 312 | 31.3 |

| No | 657 | 65.9 |

| Data not available | 28 | 2.8 |

| CD4+ lymphocyte count at enrolment (cells/mm3) | ||

| <200 | 75 | 7.5 |

| 200–350 | 191 | 19.2 |

| >350 | 511 | 51.3 |

| Data not available | 220 | 22.0 |

| Characteristics of prenatal and delivery (n=1269)a | ||

| Gestational age at the beginning of prenatal (weeks) | ||

| No prenatal visits | 127 | 10.0 |

| <14 | 227 | 17.9 |

| 14–28 | 507 | 40.0 |

| >28 | 138 | 10.9 |

| Data not available | 270 | 21.3 |

| Number of prenatal visits | ||

| None | 127 | 10.0 |

| 1–3 | 241 | 19.0 |

| 4–6 | 526 | 41.4 |

| ≥7 | 311 | 24.5 |

| Unknown | 64 | 5.0 |

| Maternity of delivery | ||

| HGNI | 960 | 75.7 |

| Other institution | 275 | 21.7 |

| Delivery outside the maternity | 22 | 1.7 |

| Data not available | 12 | 0.9 |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Elective cesarean | 531 | 41.8 |

| Vaginal | 514 | 40.5 |

| Emergency cesarean | 203 | 16.0 |

| Data not available | 21 | 1.7 |

| Membranes at delivery | ||

| No rupture | 865 | 68.2 |

| Rupture less than 3h | 88 | 6.9 |

| Rupture between 3–6h | 81 | 6.4 |

| Rupture more than 6h | 97 | 7.6 |

| Rupture not knowing time | 81 | 6.4 |

| Data not available | 57 | 4.5 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | ||

| <37 | 185 | 14.6 |

| ≥37 | 1010 | 79.6 |

| Data not available | 74 | 5.8 |

Most of the women (75.3%) lived with a partner at the time of cohort inclusion, but only 47.1% (n=469) were aware of the partner's HIV serostatus. An HIV-1-infected partner was reported by 60.1%, while 39.9% were in serodiscordant relationships. The median number of pregnancies prior to inclusion in the cohort was 2.0 (IQR: 1.0–3.0). In total, 34.3% (n=342) of the women reported having at least one abortion prior to inclusion in the cohort. Tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy were reported by 24.0%, 23.6% and 5.0% of the women, respectively. Heterosexual transmission was the predominant route of HIV infection acquisition; 30% of the women had been previously diagnosed with AIDS (CDC-1993) upon cohort enrolment.

The mean TCD4+ lymphocyte count at enrolment was 486.8 (SD: 258.7) cells/mm3; 65.8% of women had TCD4+ lymphocyte counts higher than 350 cells/mm3 (Table 1). Approximately 20% of the women were aware of their HIV serostatus when they became pregnant. Among those who were unaware of their HIV serostatus when they became pregnant (n=797), 56.3% were diagnosed during prenatal care, 22.2% during delivery and 21.5% during the immediate postpartum period (Table 1).

The characteristics of all pregnancies that resulted in delivery in the cohort (n=1269) are presented in Table 1. Prenatal care was provided for 90% of these pregnancies, mostly within the municipality of Nova Iguaçu (65.4%). The mean gestational age at the start of prenatal care was 19.9 (SD=7.7) weeks; in 40.0% and 10.9% of the pregnancies, prenatal care was initiated between 14 and 28 weeks and after the 28th week, respectively. Four or more prenatal care visits were made in 65.9% of the pregnancies (Table 1).

The majority of deliveries occurred at HGNI (75.7%). Elective cesarean delivery (41.8%) and vaginal delivery (40.5%) were the most common delivery methods. Spontaneous membrane rupture occurred in 27.3% of the deliveries that lasted longer than 3h and in at least 14% of all the deliveries. Preterm births occurred in 14.6% of the pregnancies (Table 1). One hundred and thirty-six women, with 157 pregnancies, did not have access to any prenatal care in at least one pregnancy in the cohort. The majority of them resided in the municipality of Nova Iguaçu (36.8%), followed by the municipalities of Rio de Janeiro (12.5%), Duque de Caxias (11.8%), São João de Meriti (10.3%) and Belford Roxo (10.3%) (Fig. 2).

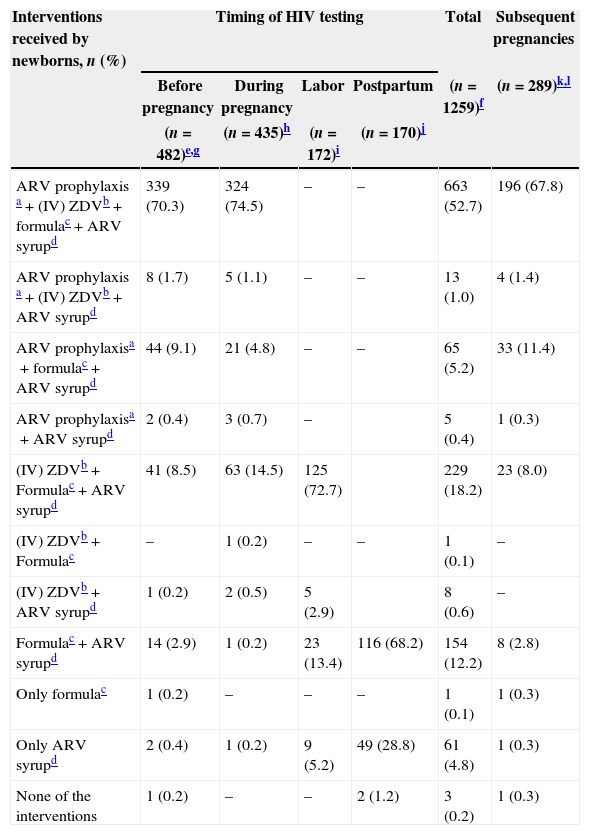

Among all newborns in the cohort with available data at the timing of maternal HIV diagnosis (n=1259), only 47.6% benefited from the recommended package of interventions for PMTCT.

The antenatal care (ANC) components of the package were used by 59.2% (n=746) of all pregnancies (n=1259) in this cohort. The global coverage of intrapartum intravenous zidovudine (IV ZDV) component was 74.1% (n=934), and 97.5% (n=1230) of the newborns had access to ZDV syrup; 85.5% (n=1077) were on antiretrovirals (ARVs) syrup for 6 weeks. Of those, 10.1% had no data regarding duration of ARVs syrup exposure. No breastfeeding (during their stay in the maternity ward) was observed in 91.0% (n=1146) of the newborns (Table 2).

PMTCT interventions delivered to pregnant women and their newborns, 1999–2009 (n=1259).

| Interventions received by newborns, n (%) | Timing of HIV testing | Total | Subsequent pregnancies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before pregnancy | During pregnancy | Labor | Postpartum | (n=1259)f | (n=289)k,l | |

| (n=482)e,g | (n=435)h | (n=172)i | (n=170)j | |||

| ARV prophylaxis a+(IV) ZDVb+formulac+ARV syrupd | 339 (70.3) | 324 (74.5) | – | – | 663 (52.7) | 196 (67.8) |

| ARV prophylaxis a+(IV) ZDVb+ARV syrupd | 8 (1.7) | 5 (1.1) | – | – | 13 (1.0) | 4 (1.4) |

| ARV prophylaxisa+formulac+ARV syrupd | 44 (9.1) | 21 (4.8) | – | – | 65 (5.2) | 33 (11.4) |

| ARV prophylaxisa+ARV syrupd | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | – | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | |

| (IV) ZDVb+Formulac+ARV syrupd | 41 (8.5) | 63 (14.5) | 125 (72.7) | 229 (18.2) | 23 (8.0) | |

| (IV) ZDVb+Formulac | – | 1 (0.2) | – | – | 1 (0.1) | – |

| (IV) ZDVb+ARV syrupd | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (2.9) | 8 (0.6) | – | |

| Formulac+ARV syrupd | 14 (2.9) | 1 (0.2) | 23 (13.4) | 116 (68.2) | 154 (12.2) | 8 (2.8) |

| Only formulac | 1 (0.2) | – | – | – | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Only ARV syrupd | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (5.2) | 49 (28.8) | 61 (4.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| None of the interventions | 1 (0.2) | – | – | 2 (1.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) |

Among 482 newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV before pregnancy, 289 were born from subsequent pregnancies during the study period.

Of the 1260 newborns, data on timing of HIV testing of the women were available for 1259. Of the 1260 newborns, 53 had missing data in at least one intervention and they do not appear in the table, as we could not define which set of interventions they received.

Of the 482 newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV before pregnancy, 29 had missing data in at least one intervention and we could not define which set of interventions they received. Among these 29, at least 8 received (IV) ZDV, 14 received formula and at least 17 received ARV syrup.

Of the 435 newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy, 14 had missing data in at least one intervention and we could not define which set of interventions they received. Among these 14, all of them received ARV prophylaxis, 8 received (IV) ZDV, 11 received formula and 6 received ARV syrup.

Of the 172 newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV during delivery, 10 had missing data in at least one intervention and we could not define which set of interventions they received. Among these 10, at least 4 received (IV) ZDV, 5 received formula and 6 received ARV syrup.

Of the 170 newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV during the postpartum period, 3 had missing data in at least one intervention and we could not define which set of interventions they received. Among these 3, 2 received formula and all 3 received ARV syrup.

Of the newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV before or during pregnancy (n=917) and who would therefore have had the opportunity to receive the entire package of intervention recommended for PMTCT, 27.7% did not have access to it. Approximately 18% (n=138) had no access to the antenatal component of the package and at least 10.4% (n=95) had not received intrapartum IV ZDV. The vast majority of the newborns (95.3%) had access to infant formula (Table 2).

Among the pregnant women diagnosed with HIV during delivery and their newborns (n=172), 72.7% received all of the recommended interventions (IV ZDV, oral ZDV and no breastfeeding) (Table 2). Of the newborns who were born to women diagnosed with HIV during the immediate postpartum period (n=171), only 67.8% received the recommended interventions. ARVs syrup was used for 6 weeks by 86% (n=147/171) of these newborns and for 6.5% there was no data available on the duration of ARVs syrup exposure. One newborn of a mother whose HIV diagnosis antedated the current pregnancy and two newborns of mothers diagnosed with HIV during the postpartum period have not received any intervention (Table 2).

When considering only the subsequent pregnancies in the cohort (n=289), in which all women were already aware of their HIV serostatus before becoming pregnant, only 67.8% of them had access to the entire package of interventions recommended for PMTCT; almost 12% of them did not have access to the antenatal components of the interventions (Table 2).

Among breastfed newborns (n=91), information on breastfeeding duration was available for 62 of them. Median and mean number of days of breastfeeding were 1 (IQR: 1–2) and 5.3 (SD 12.6).

Regarding access to the recommended interventions according to the timing of maternal HIV diagnosis and according to the year of delivery, there was no apparent trend towards accessing the cascade of interventions along the study period (before pregnancy: p=0.12; during pregnancy: p=0.09; labor: p=0.499; postpartum: p=0.627) (data not shown). Of the live-birth infants whose mothers were diagnosed with HIV at delivery and during the postpartum period in 2009, the last year of inclusion in the study, access to the recommended interventions remained unsatisfactory (80% and 67.7%, respectively) (data not shown).

The annual coverage of IV ZDV administration to newborns also fluctuated globally over the years and according to the time of maternal HIV diagnosis. In 2009, of the live-birth infants whose mothers were diagnosed with HIV before or during pregnancy and at delivery (n=96), 22.9% had not received this intrapartum component.

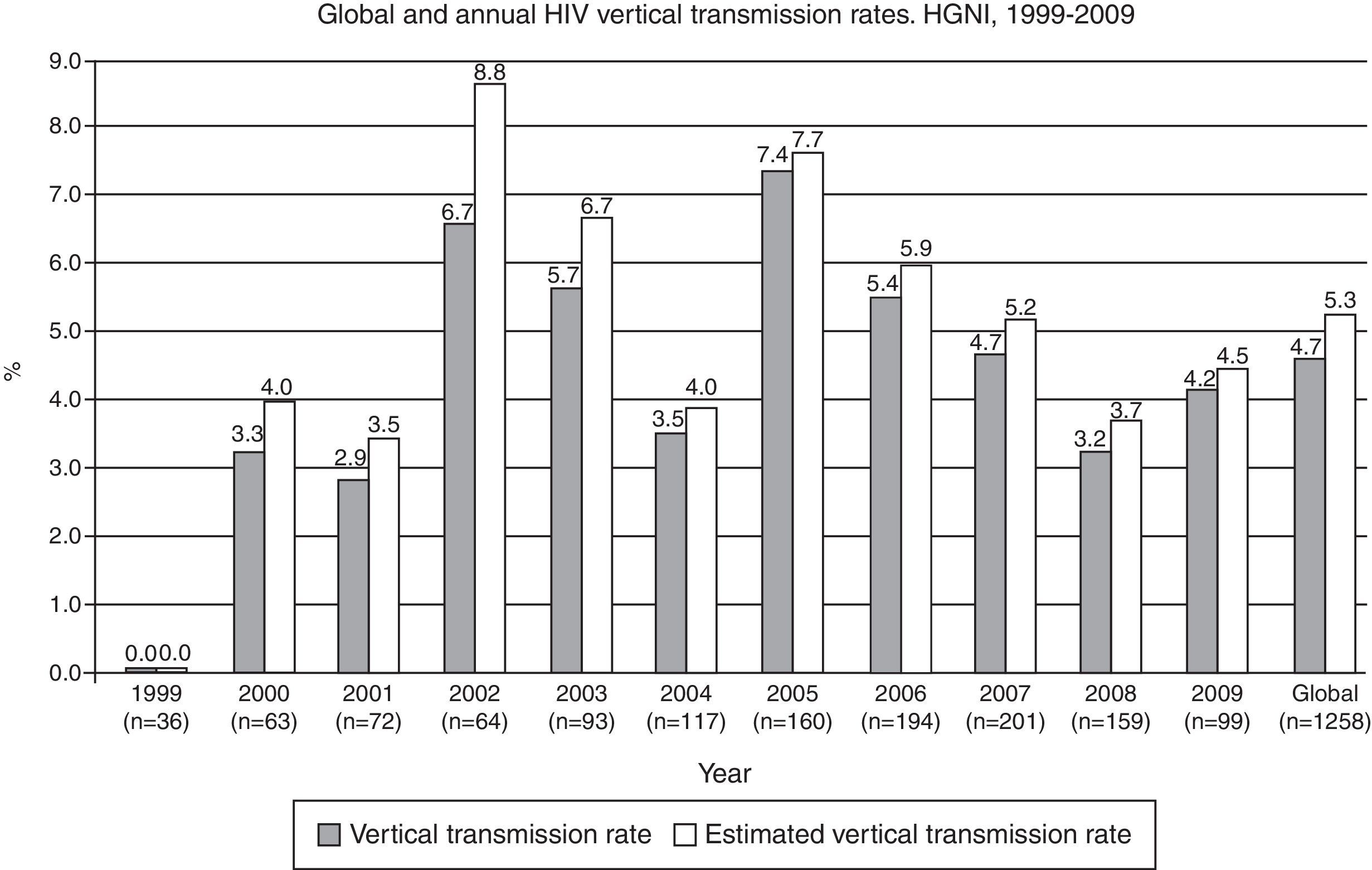

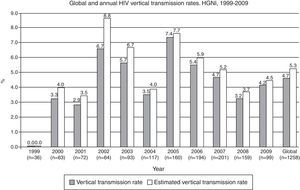

The overall rate of HIV MTCT during the study period was 4.7% (CI 95%: 3.5–5.9) (n=1258). HIV serostatus could not be determined in 223 (17.9%) newborns, due to lost to follow-up. When the MTCT rate was calculated using the assumption that the HIV infection rate was the same for those newborns in whom an HIV diagnosis was not determined, the estimated overall transmission rate was 5.3% (CI 95%: 4.1–6.5) (Fig. 3). The highest annual rate occurred in 2005 (7.4%; CI 95%: 3.3–11.5), with no definite trend in the period (data not shown). When considering only breastfed newborns (n=91), the MTCT rate was 12.1% (CI 95%: 5.4–18.8), significantly higher than the 3.9% (CI 95%: 2.8–5.0) rate observed among the non-breastfed newborns (n=1167) (p=0.0001).

DiscussionOur results shows that the HIV MTCT rates from 1999 to 2009 remained high among women who received ANC or delivered at this major referral center for PMTCT in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro.

Several studies in Brazil have reported transmission rates that are consistent with the data found in our study,3,20–25 although lower MTCT rates have been achieved in wealthier states such as São Paulo,8 as a result of a better structured health care system. Overall, the rates found in Brazil are higher than those reported from developed countries, where prophylactic measures are implemented early in pregnancy resulting in MTCT rates around 1%.26

When considering all newborns in the cohort (n=1259), only 52.7% of them benefited from the complete package of interventions that are recommended for PMTCT. Again, this result is similar to that observed for Brazil as a whole (52%) but is much lower than that observed in São Paulo where in a recent report there was 82% coverage for the entire package of PMTCT interventions.8 Despite the broad knowledge in place about the high effectiveness of ART during pregnancy for PMTCT27 and the universal availability of ARVs for this purpose in Brazil, access to the antenatal component was observed in only 59.2% of the first pregnancies included in this study. Late detection of HIV infection during prenatal care represents an opportunity to intervene, thus limiting the number of pediatric cases as a result of perinatal transmission.28

Access to HIV testing, the entry point for PMTCT during antenatal care, may be hampered by a series of events, which result in a delayed HIV diagnosis,27,29 leading to a longer fetal exposure to the virus. In many cases late diagnosis at delivery or postpartum30 leads to unacceptably high risk of HIV transmission. The lack of HIV diagnosis during pregnancy represents only the first step of a cascade of missed opportunities. Of note, 26.6% of pregnancies in which HIV infection was diagnosed before or during pregnancy have not even received one of the components of the prevention package. Among these, 32.7% have not received the antenatal component, and 9.8% have received the intrapartum component. Further studies are needed to identify strategies and interventions to overcome the barriers in place and decrease the inequalities in access to PMTCT services.

Even more worrisome is the finding that among the 289 subsequent pregnancies that resulted in live births during the study period, only 67.8% received the full package of PMTCT interventions. It is especially disconcerting that almost 20% of these subsequent pregnancies have accessed the antenatal component. Insufficient linkage to care after delivery is a well-recognized matter among HIV-infected women, and not infrequently they solely resume their contact with the health services at the time of delivery of a subsequent pregnancy. Lack of integration of health services, notably between prenatal and maternity care, may have also accounted for part of the problem in regard to access to the intrapartum and postpartum components of the PMTCT intervention package. A study conducted in Rio de Janeiro have indicated that approximately 30% of pregnant women unsuccessfully attempted to be admitted to one or more hospitals during labor,31 prior to admission for delivery, highlighting the fragile and fragmented health system in place.

Breastfeeding was observed in 9% of the newborns, similar to the rate reported in a study from Pernambuco, in the Northeast region of Brazil10 and lower than the rate reported in Sergipe, in the same region,11 leading to a significantly higher MTCT rate among breastfed newborns when compared to those non-breastfed (12.1% vs. 3.9%). In a country where formula has long been provided free of charge to HIV infected mothers, breastfeeding may, in fact, be more of a marker of poor access to health care in general. Late HIV diagnosis of the mother leads to a lost opportunity of advising against breastfeeding, which is a major factor associated with MTCT,32 and any exposure to breast milk in itself constitutes a risk factor for transmission.

Several studies have confirmed the strong relationship between the number of prenatal visits or the initiation of early prenatal care with socioeconomic status and the mother's education.27,33 Poverty is a critical determinant of health in individuals and populations, increasing the vulnerability to several diseases and is a major barrier to access to health services, information and preventive measures.34 Income and education are strongly associated with health outcomes,35 and the effects of the education level are expressed in different ways, such as the perception of health problems, the ability to understand health information, the adoption of healthy lifestyles, the consumption and utilization of health services, and the adherence to therapeutic procedures. HIV infection prevalence among pregnant women and the incidence of vertical transmission have been associated with lower urban quality of residential neighborhood in Brazil.36 Our study population was characterized by low income and education levels and a high predominance of non-white women, accurately representing the impoverished population of Baixada Fluminense. Despite the significant decrease in poverty intensity during the last years in Brazil, serious social, economic and cultural inequities continue to plague the country. These inequities include disparities related to the quality of health services, which are fairly evident in prenatal services and are still reflected in the insufficient effective access to PMTCT interventions. In order to improve engagement to care, PMTCT programs may need to evaluate alternative strategies such as incentives and additional services, including enhanced education on PMTCT and sexual transmission of HIV. Interventions that improve the engagement of pregnant women in HIV care and treatment programs are urgently needed to achieve the WHO goal of zero mother-to-child HIV transmission.37

Importantly, a high prevalence of multiparity (75%) and abortion (36.6%) was observed in this cohort, despite the high proportion of women under the age of 24, indicating the insufficiency of adequate family planning services suitable for this population. According to data from the 2006 National Household Sample Survey (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios – PNAD), the overall fertility rate in 2005 was 2.1 children per woman of childbearing age; it ranged from four (for women with up to 3 years of schooling) to 1.5 (for those who had eight or more38 years of schooling). In this context, access to comprehensive family planning services tailored to the specific needs of the HIV-infected population is a key component for effective PMTCT.

Notably, although the majority of the women (75.3%) were living with their partners at the time of inclusion in the cohort, only 47.1% were aware of their HIV serostatus, and of these women, 39.9% had an HIV-uninfected sexual partner, highlighting the substantial risk for HIV sexual transmission in these serodiscordant relationships and the critical need to implement early ART in these situations, given the 96% reduction in the risk of HIV transmission.39 Furthermore, untreated HIV infection has a negative impact on health throughout the course of the infection.40 Taken together, these data support the revised PMTCT recommendations of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, which recommend ART postpartum maintenance for all women who started it during pregnancy, regardless of the CD4 cell counts.41 The evidence that pregnancy doubles the risk of HIV transmission from pregnant women to their partners42 and the high prevalence of multiparity (75%) observed in this study population further reiterate this strategy.

This study has several limitations. As the study was conducted at a single center, the study population could not be representative of children exposed to MTCT throughout the state of Rio de Janeiro. However, this may be offset, as the chosen center, HGNI, receives the greatest regional demand for HIV-exposed children in the Baixada Fluminense area. The retrospective nature of our study has not allowed for capturing data on the barriers to PMTCT and to minimize the lost to follow-up. As our data were collected from clinical records and registries, there were missing values, which we believe have occurred randomly. Besides, we could not collect more reliable important data as viral load; thus, we could not access the association between viral load and mode of delivery and its appropriateness.

The results from this study reflect the reality of fragmented access to PMTCT interventions in Baixada Fluminense, where the municipalities with the lowest levels of development across the Rio de Janeiro State are located; approximately 25% of the population of Nova Iguaçu and Duque de Caxias are below the poverty line.

Our data provide critical insights to better understand Brazil's low overall performance in PMTCT and may help explain some of the factors related to the disconcerting occurrence of approximately 500 cases of AIDS in children under the age of five in Brazil.2 Despite the success of the Brazilian program for universal access to ART, the PMTCT program has encountered critical hurdles related to the health care system, which is still deficient and marred by serious social inequities regarding access to quality health care.33 In this context, equal access to qualified health services is essential and will positively influence the cascade of access to PMTCT interventions and decrease the number of pediatric AIDS cases in Brazil.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by Brazilian Ministry of Health, PN-DST/AIDS – SVS/Ministério da Saúde/BIRD/UNODC. Projeto AD/BRA/03/H34. Acordo de Empréstimo BIRD 4713-BR. TC 292/07.